Holding the fate of Build Back Better (BBB) in their hands, Senators Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin should heed some lessons from 2010. When a small group of Democratic senators so delayed and weakened Obamacare that they cratered Obama's initially massive support, they also helped end all their own political careers.

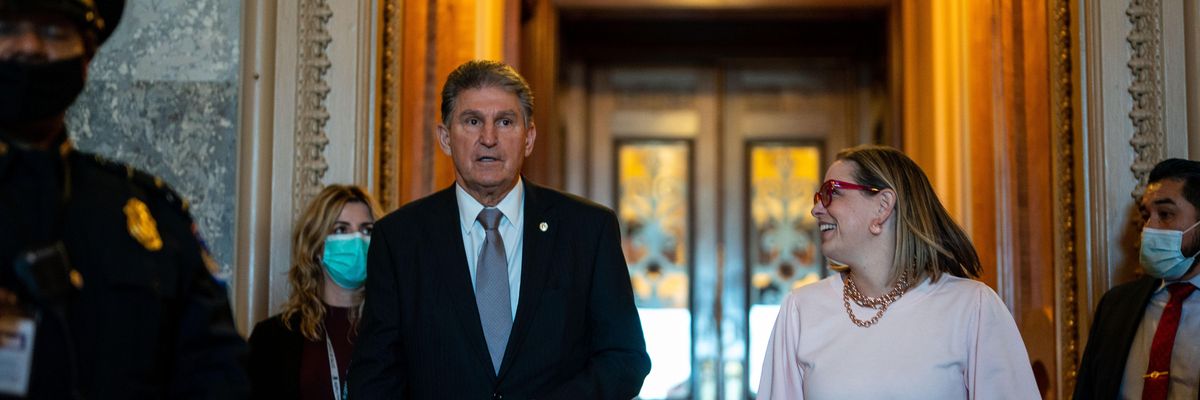

Conventional wisdom says Sinema and Manchin are resisting BBB to appease conservative and moderate supporters. But the bill would bring massive benefits for their constituents, from child support and childcare to expanded healthcare subsidies, drug price caps, and critical climate change investments. Nobel economists say it will help tame inflation, not increase it. But Manchin and Sinema's recalcitrance doesn't just block major benefits to American citizens. By placing in jeopardy everything else Biden will be able to do to address critical problems, it makes their own reelections less likely.

A similar process happened in Obama's first term. Not a single Republican cooperated with the Affordable Care Act, despite its Republican roots. But a handful of conservative Democratic senators also made the bill increasingly convoluted and less popular, as they demanded endless changes and dragged out the process. Committee chair Max Baucus of Montana burned up much of the year looking vainly for Republican support, while excluding Medicare for All advocates from even testifying. A public option offered a popular compromise, but was shot down by Nebraska's Ben Nelson, Blanche Lincoln of Arkansas, Louisiana's Mary Landreau, and Democrat-turned-independent Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, all of whom threatened to join a Republican filibuster if it was included. The negotiating team caved on government regulating on drug prices and other key cost-containment measures. Meanwhile Obama's numbers fell from 65% approval to under 45% by the 2010 midterms. Once the Republicans retook first the House and then the Senate, Obama never got another chance to pass major legislation, including on issues that Manchin and Sinema care about.

Only a few years later, senators who dragged out the process were all gone from the Senate, defeated in primaries or general elections, or deciding not to run after considering the odds. Those from conservative states would have faced tough challenges regardless. But Obama's sinking ratings pulled them down further, and key constituents stayed home in anger or frustrated demoralization. Yet senators like Montana's Jon Tester and Ohio's Sherrod Brown--who didn't derail the process--survived and held their seats, even though their states were trending conservative.

Biden's decline in approval from 53% to under 44% isn't solely due to legislative delays. But Manchin and Sinema have fed a media narrative that the Democrats are can't get things done, much as occurred with the Affordable Care Act. Had those who obstructed the ACA sped the process instead of impeding it, the electoral setbacks of 2010 and 2014 might have turned out differently, and Obama could have accomplished far more. Manchin and Sinema have similarly placed Biden's broader agenda at risk, particularly given the popularity of the elements that BBB contains.

That doesn't require them to march in lockstep with coastal liberals. It was valuable for Manchin to add an opioid tax and increased addiction treatment and prevention programs to BBB. His crafting of the Freedom to Vote Act as a voting rights compromise could be key to saving democracy itself--although only if he's willing to change the filibuster to get it passed. But neither Manchin nor Sinema gain by preventing their colleagues from addressing urgent common challenges.

When Manchin and Sinema next run in 2024, Biden's standing will play a critical role in their chances. In Sinema's case, key groups that worked to get her elected need to show up again, but until recently she wouldn't even meet with them, fueling serious talk of a primary challenge. And by opposing taxes on the wealthy and corporations that Manchin supported, Sinema made it easier for him to claim it wasn't sufficiently paid for. Manchin faces a more conservative electorate in West Virginia, although Democrats and Republicans remain roughly tied in party registration there. So he'll need every supportive vote he can get, and his 2024 chances will improve hugely if Biden loses by say 20 points instead of 40. Meanwhile neither can afford to have core supporters staying home in anger and frustration. As 2010 reminds us, the more they drag the administration down, the more they damage their own futures. And if they can finally stop obstructing, they can give the Biden administration at least a fighting chance to address the key problems of our time.