January 20th's disastrous mediation between striking concrete mix truckers and the kingpins of Seattle's sand and gravel industry had already hit a wall when Teamsters Local 174 shop steward Todd Parker got a text telling him another one of their members--a popular guy named "Mikey" in recovery from addiction--had just been found dead inside his apartment.

According to the union, the 46-year-old's tragic overdose came after an uncharacteristically late night out that would not have occurred had workers not been sidelined for the past two months, and followed closely behind the horrific death of another hard-pressed striker going through a divorce and grappling with money problems who committed suicide just a few weeks prior.

"When you have all this downtime your demons and addictions kick back in," the 50-year-old Parker told me from the strike line. "Mikey had worked for us maybe three years. He was a very, very well-liked guy--everybody liked him. He just had that kind of personality where he'd draw people in and was always happy-go-lucky. It's been hard on everybody--it's still hard on everybody. We talked about it today--he would have been [safely] at home [that night] if we were working."

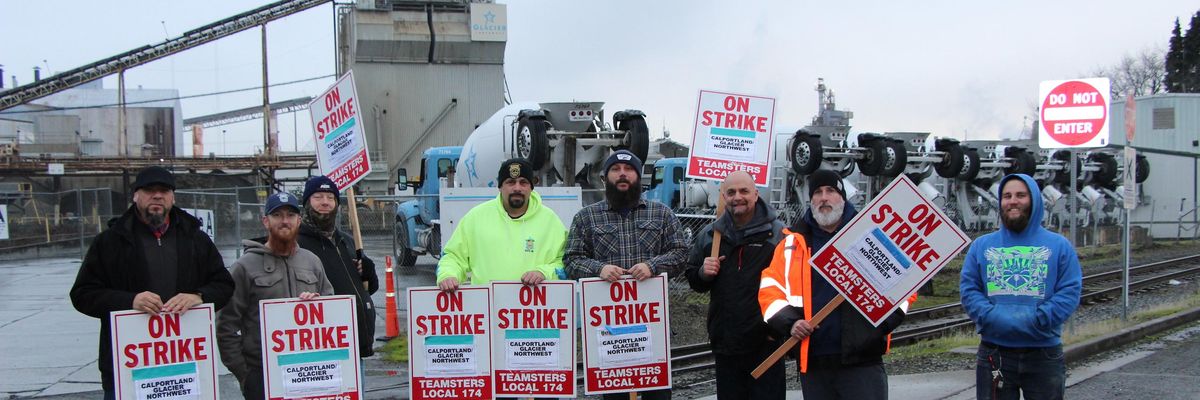

The two-month-old strike involving more than 300 union truckers and concrete plant workers in Seattle has prompted U.S. Labor Secretary Marty Walsh to personally intervene in an effort to to finally resolve a standoff that is taking huge chunks out of Seattle's $23 billion construction industry and proving lethal--at least for workers finding it increasingly difficult to sustain themselves and their families.

Experts call the kinds of casualties Teamsters Local 174 is experiencing during the ongoing strike "deaths of despair."

Suicide remains the second leading cause of death for people ages 10-34, the fourth leading cause among people ages 35-44, and the fifth leading cause among people ages 45-54.

The National Center for Health Statistics estimates drug overdoses caused the deaths of 100,306 people in the U.S. between April 2020 and April 2021. That's a nearly 30-percent increase in fatalities over the year prior. Use of the biggest killers--fentanyl, methamphetamine and cocaine--are all on the rise.

Andy Johnson, fund administrator for the Teamster Center Services Fund, says that although Covid has dominated the news cycle for the past two years, suicide and deaths caused by drug overdoses cannot be overlooked.

"While both suicide and drug overdoses are complex issues with many contributing factors, it is important for everyone to 'be thy brother's keeper' and be aware of distress signals coming from friends, family and coworkers," he says. "The simple question, 'How are you doing?' and the willingness to really listen can go a long way as we all work together to get through this uncertain and difficult time."

At 47, Local 174 trucker and father of three Brett Gallagher is just a year older than his fallen union brother Mikey. Other heavy haul drivers in the region, according to Gallagher, earn $10 more an hour than he and his hardworking colleagues--and they want parity.

"We don't feel respected," the former certified paint tech and bargaining committee member says. "We don't feel like we're being taken seriously."

Local 174 says employers are trying to force a subpar wage, healthcare and retirement package on members that is significantly less than the compensation packages other Seattle construction workers receive--one that would actually make them worse off than they already are given inflation.

"The contract hadn't even expired yet and they said, 'We can't reach a decision; we want a mediator," Gallagher told me. "We kept going, we kept working, we kept bargaining, we kept pushing. It came to a point where negotiations broke off and we couldn't even get them to answer the phone. At that point, we decided we can't just sit back and be bullied around anymore--we've got to make a decision--we decided to go on strike."

Local 174 members working for six of the biggest players in the region, including a couple of transnationals--a German outfit called HeidelbergCement and the Japanese-based Taiheiyo Cement--saw their contract expire in July. They didn't walk out in large numbers, however, until December 3, following months of what the union charges was bad faith bargaining on behalf of the bosses.

Concrete mixer trucks are upwards of 70,000 lb. behemoths that drivers somehow must navigate through increasingly chaotic and congested streets in Seattle, where "every easy to build place has already been built."

"[Developers are] looking for any spare scrap of real estate they can find and build as much square footage as they can on it, which literally means we're being squeezed tighter and tighter into smaller areas and more technically challenging situations," Gallagher says. "A lot of the times, if we enter a job site we have to back up further than we are moving forward."

The typically grueling 10- to 12-hour days leave just enough time for drivers to "go home, have dinner, kiss the kids goodnight, shower and go to bed. Then get back up again."

"It takes a strong gut to get that [truck] through the city," 36-year-old cement mix truck driver Tim Davis says. "You can train for it, but there are always difficult real life situations. You've got to know what kind of soil you can drive on; if the grass is going to give out; you don't know if it's going to be soft soil. It takes experience to know that. We try to do this day in and day out safely--that's the key."

Striking concrete workers are also about to see their employer-based healthcare expire. Meanwhile, four of the biggest general contracting and engineering outfits in the country --Kiewit Corporation, Hoffman Construction Company, Flatiron West, Inc. and Kuney Construction--are so concerned about how the strike is impacting the modernization of Microsoft's Redmond campus, the Sound Transit system expansion project and the renovations of Sea-Tac Airport's runway and Seattle's waterfront, they are threatening legal action.

Should that effort prove successful, the union says it could set "a nationally catastrophic precedent for workers that would interfere with their federally protected right to strike."

Davis is also a father with two young daughters at home. He, like the rest of his striking co-workers, wonders how he'll be able provide for his family should the standoff continue to drag on, and what the future might hold for them if concrete workers lose the strike.

"I go to work every single day; I work hard," Davis says. "Most of us take pride in what we do--we expected to be treated better than this. Now, we're out of work and have families to support. I have two daughters to support. And that's just me--there are over 300 of our guys out there and it affects their families --that's more than three hundred families."

The companies have characterized at least one previous offer as "generous and historic." But Local 174 says the employers had zero to offer workers during the failed January 20 attempt at mediation.

"We've moved literal dollars to get to the middle ground and they've moved pennies --and then they just quit," Gallagher says.

After learning about the death of a second Local 174 striker, Parker reportedly told a supervisor at the last bargaining session that the ongoing strike is causing members to lose their lives "and you guys are doing nothing about it."

"Not one of them after that incident has ever reached out to us about any of this," he says. "This is how we're being treated--they just don't care. We're just a number to them."

Seattle's concrete trucker strike is occurring at the same time efforts are underway nationwide to allow teenagers as young as 18 to obtain interstate commercial drivers licenses.

Gallagher calls that "absolutely asinine."

"Instead of raising the wages to get more people involved in this business, you literally go out and lobby to reduce the parameters of being qualified to do this job. That's nuts," he says.

After working through the pandemic--at the risk of themselves and their families --Parker is left wondering "what we've ever done to [the employers] to be treated like this."

"We're essential workers," he says. "We've worked through this whole pandemic. We've had to worry about bringing Covid home to our families. Obviously, we've had plenty of people who have gotten it --we've had people who have been in the hospital over it. It's just a complete and utter lack of respect we've gotten from our employers."

If nothing else, he says the ongoing strike in Seattle and the terrible toll it is having on working families has been revelatory.

"They've shown their true colors," he says. "These large corporations--these one-percenters--have too much control. They don't care about their workforce anymore. They don't care if we get by in life. The only thing they care about is what we do for them--and that's make them money."