The Supreme Court's decision to hear a redistricting case from Alabama next term puts the Voting Rights Act once again in the sights of an increasingly conservative high court--this time with the potential for a wholesale rollback of long-established protections for communities of color in redistricting.

Having rolled back the Voting Rights Act's protections in ways big and small over the last decade, the Supreme Court could be prepared to do yet more damage at just the point that a new multiracial America is emerging.

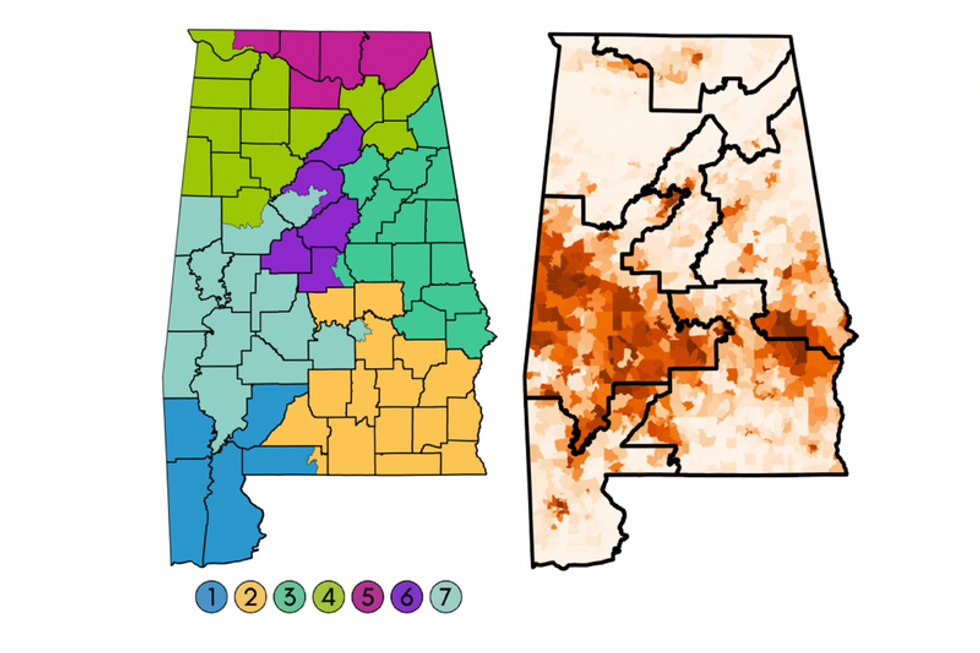

The case centers on whether Alabama has an obligation under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act to create a second district where Black voters have a reasonable opportunity to elect community-preferred candidates. Black Alabamians are currently 27 percent of the state's population, but under the map passed by the Republican controlled Alabama legislature, have the ability to successfully elect candidates in only one of the state's seven congressional districts.

This anomalous result is the product of a carefully constructed two-step maneuver. First, lawmakers packed a large portion of Black Alabamians into the sprawling, heavily Black 7th Congressional District, which joins much of the state's historic Black Belt with parts of both Birmingham and Montgomery. For the rest of the state, map drawers then surgically divided Black voters among the remaining six white-majority districts. The outcome is a map where the 7th District is more than 56 percent Black, but where no other district is more than 30 percent Black, well below the level needed for Black Alabamians to sway elections given the high levels of racially polarized voting in the state.

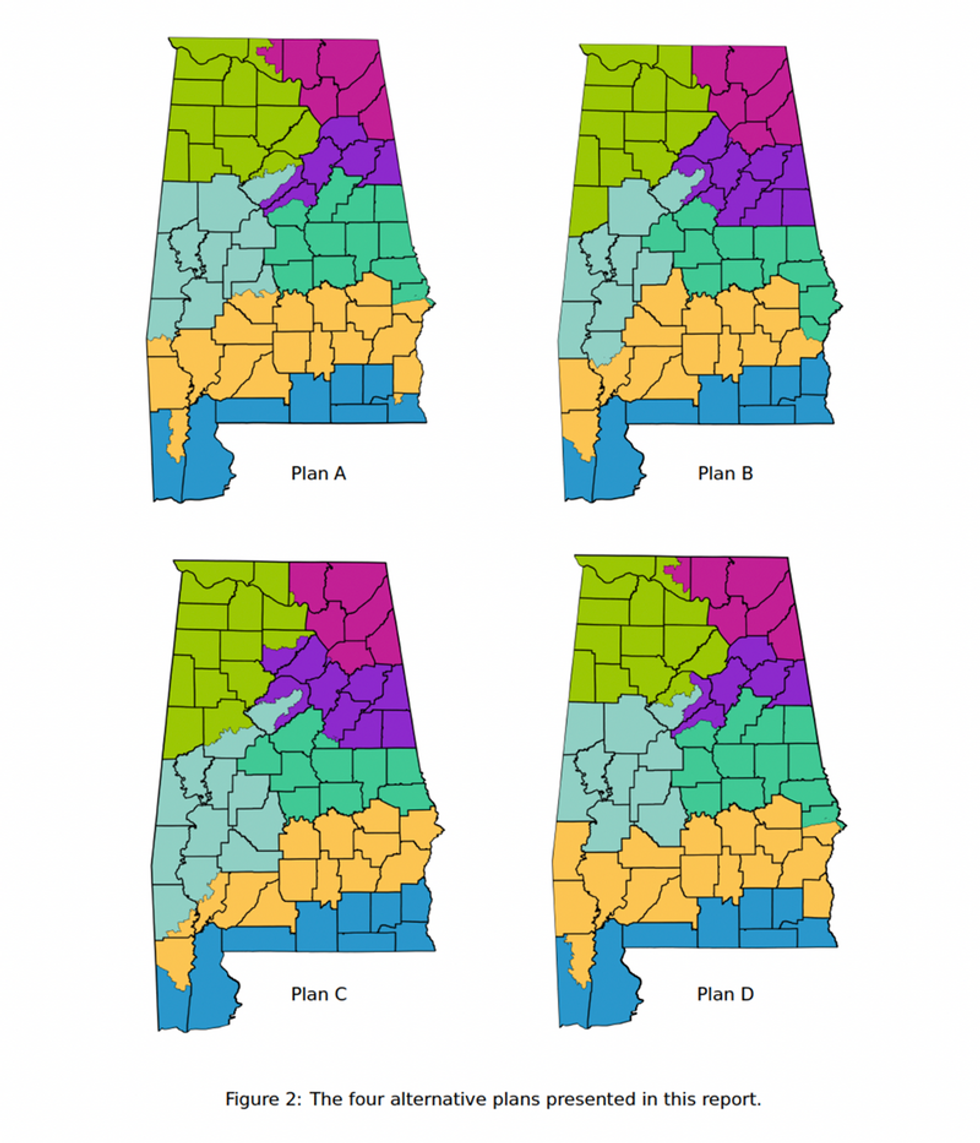

Black voters and organizations challenged the map in federal court, arguing that it would be easy to undo the packing and cracking of Black voters to create two reasonably compact Black majority districts that place most of the rural Black Belt in two congressional districts rather than four as under the map passed by the legislature.

A three-judge panel, including two judges appointed by President Trump, unanimously agreed in a 225-page opinion, finding that racially polarized voting meant that Black communities' candidates rarely won election other than in districts created because of the VRA. The court also found that Black voters still faced significant discrimination in Alabama political life, including the use of racialized appeals in voting. The court gave Alabama two weeks to redraw the map to create a second Black congressional district.

Under longstanding precedent, the Alabama case is about as straightforward as they come. To remedy the effects of racial discrimination, principles first laid out by the Supreme Court in 1986 in Thornburg v. Gingles require a state to create a district that gives minority voters a chance to elect a candidate if a minority community can show that it is "sufficiently large and geographically compact" to be a majority in "some reasonably configured district" and other strict conditions are met. Some awareness and consideration of race is, by necessity, part of this analysis. Subsequent Supreme Court cases provide that race cannot "predominate" in the drawing of districts (for example, joining together far-flung minority communities that have little in common beyond race), but courts have never said that any consideration of race was unconstitutional.

In appealing, Alabama has asked the Supreme Court to undo four decades of precedent to impose a rule that no liability under the Voting Rights Act will exist unless it is possible to create a minority district while at the same time complying with all of state's "race-neutral criteria" in their entirety. According to Alabama, allowing a map to deviate from a state's "race neutral criteria" in order to create a minority district would mean that a district unconstitutionally prioritizes race.

At a minimum, the Supreme Court's decision to hear the case means that the map struck down by the lower court will remain in place for the 2022 midterm elections. But taking the case also ominously signals a willingness from the justices to reconsider the question of whether race can be considered at all in complying with the Voting Rights Act--or whether, in the words of one of plaintiffs, litigants must ignore race and "blindly stumble around [a] map, hoping they might just happen to run into a new majority-Black district."

A win for Alabama would cripple the ability of communities of color to win relief under the Voting Rights Act. States' existing "race neutral" rules would trump all else and could never be violated when complying with the law. Incumbency protection, preserving political boundaries set in stone a century or more ago, strict rules on compactness--all would take priority over minority representation. Worse, states could adopt any number of facially neutral redistricting rules engineered in reality to make it all but impossible to draw minority districts. It, in short, would be the end of the VRA as we know it, effectively subordinating federal law to state law.

Having rolled back the Voting Rights Act's protections in ways big and small over the last decade, the Supreme Court could be prepared to do yet more damage at just the point that a new multiracial America is emerging.