A woman speaks during a protest against recently passed abortion ban bills at the Georgia State Capitol building, on May 21, 2019 in Atlanta, Georgia.

GOP Curbing Access to Medication Abortions Across the South

State lawmakers in Georgia as well as South Carolina are fast-tracking bills that would set up new roadblocks for people seeking medication abortions—and that would have doctors disseminate potentially dangerous disinformation about reversing medication abortions.

When the Food and Drug Administration announced in December that it would permanently allow the drugs used for medication abortion to be delivered through the mail, it seemed like a victory for abortion access--especially during the coronavirus pandemic, which has expanded the use of telemedicine for health care.

"We need our legislators to stop playing politics with our medical decisions and stop the bans on our bodies."

But the new FDA policy won't necessarily benefit people seeking to end pregnancies in the South, where most states already impose overriding restrictions that require medication abortions be given in person by a doctor. Meanwhile, lawmakers in two states in the South--Georgia and South Carolina--are considering bills that would further restrict access to medication abortion.

First approved by the FDA nearly 22 years ago, medication abortion is a fairly common and safe abortion procedure available to people who are up to 10 weeks pregnant. In 2019, 42.6% of U.S. abortions were medical, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The medications used are mifepristone, which essentially blocks pregnancy hormones, and misoprostol, which is taken up to 48 hours after the first drug and causes uterine cramps to complete the abortion, explained Dr. Amy Bryant, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

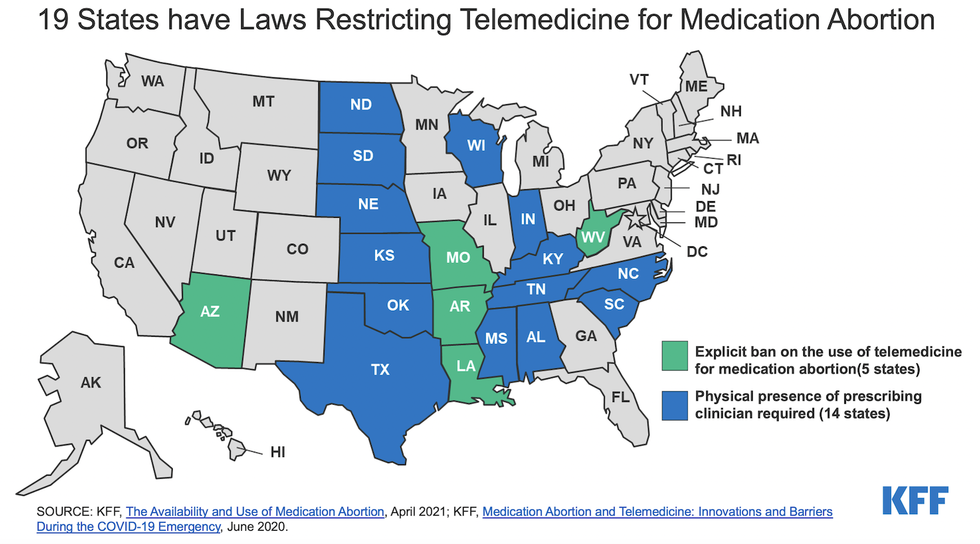

Across the U.S., 33 states currently require abortion medications to be provided by a doctor and 19 states restrict the use of telemedicine for a medication abortion, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Among the 13 Southern states, telemedicine abortion is currently legal only in Florida, Georgia, and Virginia.

Access to abortion care through medication and telemedicine helps many Southerners in need, said Oriaku Njoku, the co-founder of Access Reproductive Care-Southeast, a reproductive justice-focused abortion fund that serves people in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee. According to research the group released with the Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, 46% of Georgians who sought ARC-Southeast's support from 2017 to 2019 had to travel 25 miles or more to access care, a problem that could be eliminated by medication abortion with telehealth support.

Medication abortion "offers an alternative for people to have their abortions in their own chosen settings," Njoku told Facing South in an email. " And the unfortunate reality for us is that 95% of counties in Georgia do not have abortion providers. This means that many Georgians are forced to travel to access abortion care."

But now state lawmakers in Georgia as well as South Carolina are fast-tracking bills that would set up new roadblocks for people seeking medication abortions--and that would have doctors disseminate potentially dangerous disinformation about reversing medication abortions. The move, which comes amid a broader Republican assault on abortion rights, has outraged many in the medical community.

"Forcing doctors to provide false information to patients violates really all standards of medical care and ethics," said Dr. Dawn Bingham, an obstetrician-gynecologist in South Carolina who testified against the legislation last month. "When you have nonmedical, nonlicensed people prescribing medical therapies, it is tantamount to practicing medicine without a license."

Legislating disinformation

While Georgia severely restricts abortion, it currently allows access to medication abortions through telemedicine thanks to a July 2020 federal court ruling, as Scalawag has reported. But a bill approved this week by the state Senate Health and Human Services Committee would ban the practice. Senate Bill 456, which was introduced on Feb. 7 and has 31 Republican sponsors, would require medication abortions be done by a doctor.

The bill also says doctors "may instruct the patient that it may be possible to reverse the effects of the chemical abortion should she change her mind"--allowing them to provide information about taking progesterone, a hormone that anti-abortion advocates promote as reversing the effects of mifepristone. However, the use of progesterone to reverse a medication abortion is controversial. A professor at the University of California, Davis who studied the procedure in 2019 ended the study for safety reasons after three of the dozen people he tested it on ended up being transported by ambulance to the hospital for heavy vaginal bleeding.

"The problem with these bills is they try to sound like medical documents but are written by non-medical people who have no business practicing medicine by legal decree," Dr. Mimi Zieman, a writer and obstetrician-gynecologist in Georgia, told Facing South in an email.

Last month, Republican lawmakers in South Carolina introduced Senate Bill 988, titled the "Equal Protection for Unborn Babies Act." The bill defines life as beginning at conception and would essentially ban most abortions--including medication abortions--except in cases where the mother's life is endangered. It's what's known as a "trigger bill" that would take effect if and when the U.S. Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade.

As in Georgia, Republican lawmakers in South Carolina also want to use their power to promote questionable information about medication abortion. In December, two GOP state senators introduced Senate Bill 907 requiring a statement be attached to packages of misoprostol that says in part, "If, after taking the first pill, you would like to change your decision, please consult a physician or health care provider immediately to determine whether there are options available to assist you in continuing your pregnancy. Medication is also available by prescription to help restore progesterone and potentially strengthen the pregnancy if you and your physician make that decision."

Advocacy groups in South Carolina are planning to protest at the statehouse in Columbia on Feb. 17, when the two anti-abortion bills are expected to be heard by the full state Senate Medical Affairs committee.

"Both bills have dire consequences for pregnant people, no matter if they decide to continue a pregnancy or not," the Palmetto State Abortion Fund said in a statement. "We need our legislators to stop playing politics with our medical decisions and stop the bans on our bodies."

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

When the Food and Drug Administration announced in December that it would permanently allow the drugs used for medication abortion to be delivered through the mail, it seemed like a victory for abortion access--especially during the coronavirus pandemic, which has expanded the use of telemedicine for health care.

"We need our legislators to stop playing politics with our medical decisions and stop the bans on our bodies."

But the new FDA policy won't necessarily benefit people seeking to end pregnancies in the South, where most states already impose overriding restrictions that require medication abortions be given in person by a doctor. Meanwhile, lawmakers in two states in the South--Georgia and South Carolina--are considering bills that would further restrict access to medication abortion.

First approved by the FDA nearly 22 years ago, medication abortion is a fairly common and safe abortion procedure available to people who are up to 10 weeks pregnant. In 2019, 42.6% of U.S. abortions were medical, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The medications used are mifepristone, which essentially blocks pregnancy hormones, and misoprostol, which is taken up to 48 hours after the first drug and causes uterine cramps to complete the abortion, explained Dr. Amy Bryant, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Across the U.S., 33 states currently require abortion medications to be provided by a doctor and 19 states restrict the use of telemedicine for a medication abortion, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Among the 13 Southern states, telemedicine abortion is currently legal only in Florida, Georgia, and Virginia.

Access to abortion care through medication and telemedicine helps many Southerners in need, said Oriaku Njoku, the co-founder of Access Reproductive Care-Southeast, a reproductive justice-focused abortion fund that serves people in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee. According to research the group released with the Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, 46% of Georgians who sought ARC-Southeast's support from 2017 to 2019 had to travel 25 miles or more to access care, a problem that could be eliminated by medication abortion with telehealth support.

Medication abortion "offers an alternative for people to have their abortions in their own chosen settings," Njoku told Facing South in an email. " And the unfortunate reality for us is that 95% of counties in Georgia do not have abortion providers. This means that many Georgians are forced to travel to access abortion care."

But now state lawmakers in Georgia as well as South Carolina are fast-tracking bills that would set up new roadblocks for people seeking medication abortions--and that would have doctors disseminate potentially dangerous disinformation about reversing medication abortions. The move, which comes amid a broader Republican assault on abortion rights, has outraged many in the medical community.

"Forcing doctors to provide false information to patients violates really all standards of medical care and ethics," said Dr. Dawn Bingham, an obstetrician-gynecologist in South Carolina who testified against the legislation last month. "When you have nonmedical, nonlicensed people prescribing medical therapies, it is tantamount to practicing medicine without a license."

Legislating disinformation

While Georgia severely restricts abortion, it currently allows access to medication abortions through telemedicine thanks to a July 2020 federal court ruling, as Scalawag has reported. But a bill approved this week by the state Senate Health and Human Services Committee would ban the practice. Senate Bill 456, which was introduced on Feb. 7 and has 31 Republican sponsors, would require medication abortions be done by a doctor.

The bill also says doctors "may instruct the patient that it may be possible to reverse the effects of the chemical abortion should she change her mind"--allowing them to provide information about taking progesterone, a hormone that anti-abortion advocates promote as reversing the effects of mifepristone. However, the use of progesterone to reverse a medication abortion is controversial. A professor at the University of California, Davis who studied the procedure in 2019 ended the study for safety reasons after three of the dozen people he tested it on ended up being transported by ambulance to the hospital for heavy vaginal bleeding.

"The problem with these bills is they try to sound like medical documents but are written by non-medical people who have no business practicing medicine by legal decree," Dr. Mimi Zieman, a writer and obstetrician-gynecologist in Georgia, told Facing South in an email.

Last month, Republican lawmakers in South Carolina introduced Senate Bill 988, titled the "Equal Protection for Unborn Babies Act." The bill defines life as beginning at conception and would essentially ban most abortions--including medication abortions--except in cases where the mother's life is endangered. It's what's known as a "trigger bill" that would take effect if and when the U.S. Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade.

As in Georgia, Republican lawmakers in South Carolina also want to use their power to promote questionable information about medication abortion. In December, two GOP state senators introduced Senate Bill 907 requiring a statement be attached to packages of misoprostol that says in part, "If, after taking the first pill, you would like to change your decision, please consult a physician or health care provider immediately to determine whether there are options available to assist you in continuing your pregnancy. Medication is also available by prescription to help restore progesterone and potentially strengthen the pregnancy if you and your physician make that decision."

Advocacy groups in South Carolina are planning to protest at the statehouse in Columbia on Feb. 17, when the two anti-abortion bills are expected to be heard by the full state Senate Medical Affairs committee.

"Both bills have dire consequences for pregnant people, no matter if they decide to continue a pregnancy or not," the Palmetto State Abortion Fund said in a statement. "We need our legislators to stop playing politics with our medical decisions and stop the bans on our bodies."

When the Food and Drug Administration announced in December that it would permanently allow the drugs used for medication abortion to be delivered through the mail, it seemed like a victory for abortion access--especially during the coronavirus pandemic, which has expanded the use of telemedicine for health care.

"We need our legislators to stop playing politics with our medical decisions and stop the bans on our bodies."

But the new FDA policy won't necessarily benefit people seeking to end pregnancies in the South, where most states already impose overriding restrictions that require medication abortions be given in person by a doctor. Meanwhile, lawmakers in two states in the South--Georgia and South Carolina--are considering bills that would further restrict access to medication abortion.

First approved by the FDA nearly 22 years ago, medication abortion is a fairly common and safe abortion procedure available to people who are up to 10 weeks pregnant. In 2019, 42.6% of U.S. abortions were medical, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The medications used are mifepristone, which essentially blocks pregnancy hormones, and misoprostol, which is taken up to 48 hours after the first drug and causes uterine cramps to complete the abortion, explained Dr. Amy Bryant, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill.

Across the U.S., 33 states currently require abortion medications to be provided by a doctor and 19 states restrict the use of telemedicine for a medication abortion, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Among the 13 Southern states, telemedicine abortion is currently legal only in Florida, Georgia, and Virginia.

Access to abortion care through medication and telemedicine helps many Southerners in need, said Oriaku Njoku, the co-founder of Access Reproductive Care-Southeast, a reproductive justice-focused abortion fund that serves people in Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Tennessee. According to research the group released with the Center for Reproductive Health Research in the Southeast, 46% of Georgians who sought ARC-Southeast's support from 2017 to 2019 had to travel 25 miles or more to access care, a problem that could be eliminated by medication abortion with telehealth support.

Medication abortion "offers an alternative for people to have their abortions in their own chosen settings," Njoku told Facing South in an email. " And the unfortunate reality for us is that 95% of counties in Georgia do not have abortion providers. This means that many Georgians are forced to travel to access abortion care."

But now state lawmakers in Georgia as well as South Carolina are fast-tracking bills that would set up new roadblocks for people seeking medication abortions--and that would have doctors disseminate potentially dangerous disinformation about reversing medication abortions. The move, which comes amid a broader Republican assault on abortion rights, has outraged many in the medical community.

"Forcing doctors to provide false information to patients violates really all standards of medical care and ethics," said Dr. Dawn Bingham, an obstetrician-gynecologist in South Carolina who testified against the legislation last month. "When you have nonmedical, nonlicensed people prescribing medical therapies, it is tantamount to practicing medicine without a license."

Legislating disinformation

While Georgia severely restricts abortion, it currently allows access to medication abortions through telemedicine thanks to a July 2020 federal court ruling, as Scalawag has reported. But a bill approved this week by the state Senate Health and Human Services Committee would ban the practice. Senate Bill 456, which was introduced on Feb. 7 and has 31 Republican sponsors, would require medication abortions be done by a doctor.

The bill also says doctors "may instruct the patient that it may be possible to reverse the effects of the chemical abortion should she change her mind"--allowing them to provide information about taking progesterone, a hormone that anti-abortion advocates promote as reversing the effects of mifepristone. However, the use of progesterone to reverse a medication abortion is controversial. A professor at the University of California, Davis who studied the procedure in 2019 ended the study for safety reasons after three of the dozen people he tested it on ended up being transported by ambulance to the hospital for heavy vaginal bleeding.

"The problem with these bills is they try to sound like medical documents but are written by non-medical people who have no business practicing medicine by legal decree," Dr. Mimi Zieman, a writer and obstetrician-gynecologist in Georgia, told Facing South in an email.

Last month, Republican lawmakers in South Carolina introduced Senate Bill 988, titled the "Equal Protection for Unborn Babies Act." The bill defines life as beginning at conception and would essentially ban most abortions--including medication abortions--except in cases where the mother's life is endangered. It's what's known as a "trigger bill" that would take effect if and when the U.S. Supreme Court overturns Roe v. Wade.

As in Georgia, Republican lawmakers in South Carolina also want to use their power to promote questionable information about medication abortion. In December, two GOP state senators introduced Senate Bill 907 requiring a statement be attached to packages of misoprostol that says in part, "If, after taking the first pill, you would like to change your decision, please consult a physician or health care provider immediately to determine whether there are options available to assist you in continuing your pregnancy. Medication is also available by prescription to help restore progesterone and potentially strengthen the pregnancy if you and your physician make that decision."

Advocacy groups in South Carolina are planning to protest at the statehouse in Columbia on Feb. 17, when the two anti-abortion bills are expected to be heard by the full state Senate Medical Affairs committee.

"Both bills have dire consequences for pregnant people, no matter if they decide to continue a pregnancy or not," the Palmetto State Abortion Fund said in a statement. "We need our legislators to stop playing politics with our medical decisions and stop the bans on our bodies."