For years now, any discussion about climate action or the need to move off fossil fuels has run headlong into a familiar quandary: The industries fueling the climate crisis create good jobs, often in areas of the country where finding work that can support a family is incredibly difficult.

Since 2014, oil and gas employment has fallen 33 percent, while production has risen 32 percent. While this might be Wall Street's ideal mode of capitalism--huge profits and lower labor costs--it's obviously not one that serves the interests of workers.

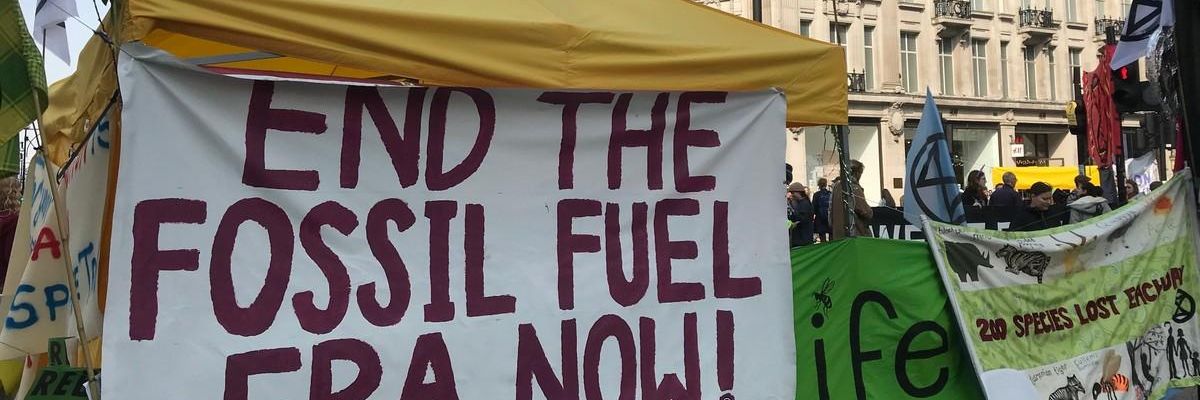

This leaves activists gesturing towards well-intentioned goals like a "just transition," a promise that likely rings hollow for workers and many labor unions because it's hard to see where this has actually happened--even though, by every measure, we need to create some real policies that turn this vision into reality. While there are encouraging examples of labor unions throwing their support behind robust climate plans, it has proven difficult for the climate movement to find its way out of the jobs versus environment framing.

But that is especially true when we refuse to question the original premise. The truth is that the fossil fuel industry wildly inflates its employment record, and the recent data show they are producing more fuel with fewer workers. Instead of avoiding this reality, perhaps it is time to tackle it head on. Dirty energy corporations are not creating jobs as much as they are cutting them these days, and that provides an opening to envision the kinds of employment--in areas like orphaned well clean up and energy efficiency--that will provide employment for the thousands of workers the industry is no longer employing.

Some of the most common jobs estimates are produced by the American Petroleum Institute (API), the powerful oil and gas trade association. Over the years, API has released reports claiming that the domestic fracking industry creates somewhere between 2.5 million to 11 million jobs, both directly and indirectly. These numbers--or versions of them--are floated in political debates and in the media, but they are significantly out of step with other estimates, including the federal government's labor reports. Food & Water Watch, an organization I founded, created a more accurate model that relies on direct jobs and relevant support activities, including pipeline construction and product transportation. The total comes to just over 500,000 in 2020, or about 0.4 percent of all jobs in the country.

How to explain the massive gap between industry propaganda and reality? The API figures include a range of employment categories; in addition to direct industry employment, they add indirect jobs (those within a supply chain) and induced jobs (those that are supposedly 'supported' by direct and indirect jobs). These categories make up the vast majority of their total. Convenience store workers, for example--working where gas happens to be sold--make up almost 35 percent of the industry's supposed employment record.

These wildly inaccurate figures can form the basis for tired debates pitting "jobs versus the environment," which remain politically potent. In 2020, when all eyes were fixed on Pennsylvania's 20 electoral votes, Donald Trump made campaign stops in the state declaring that Joe Biden would kill hundreds of thousands of fracking jobs. (Biden, of course, countered by saying that he had no such intentions to rein in drilling.) That framing of the issue, fueled by countless other media reports, reinforces the idea that gas drilling is an especially important jobs bonanza in Pennsylvania, and that Democrats would be wise to continue to support fracking--never mind the cost to clean air, water, climate and human health. The same dynamic is already one of the themes in the state's Senate Democratic primary race.

But despite the fossil fuel propaganda, the oil and gas industries employ relatively few Pennsylvanians--fewer than 25,000 workers in 2020. This was a sharp drop in the workforce, and it's not all linked to Covid-19. These jobs have been on the decline since the state's "boom" years. The story is the same nationally: Since 2014, oil and gas employment has fallen 33 percent, while production has risen 32 percent. While this might be Wall Street's ideal mode of capitalism--huge profits and lower labor costs--it's obviously not one that serves the interests of workers.

The trends are clear: After the drilling boom encouraged by the Obama administration, fracking jobs are declining. The political debate rarely acknowledges this reality, and our failure to challenge the industry's spin is dangerous; it reinforces the notion that climate activists are eager to sacrifice high --paying jobs for the broader goal of decarbonization. It's hard to imagine how to 'win' that argument unless we are willing to confront it head on: Fossil fuel companies are shedding workers, pay is stagnant, and the drilling companies are pulling more oil and gas out of the ground while registering astonishing profits. This is not a record that the industry can plausibly defend as being good for workers, frontline communities, or the planet.