No sooner had Roman Abramovich, newly targeted by the United Kingdom's sanctions on Russian oligarchs, announced that he was selling Chelsea Football Club than the feeding frenzy began. An athletics icon, City grandees, and even a respected Times columnist, each representing different American multi-billionaires, descended on London in a race to buy the club. Meanwhile, a host of London properties belonging to Russian oligarchs entered a long-overdue process of liquidation. What took so long?

In terms of magnitude, American plutocrats match every dollar that Russian plutocrats stash abroad to escape scrutiny with $10 of their own.

To put it bluntly: the West's legal foundations.

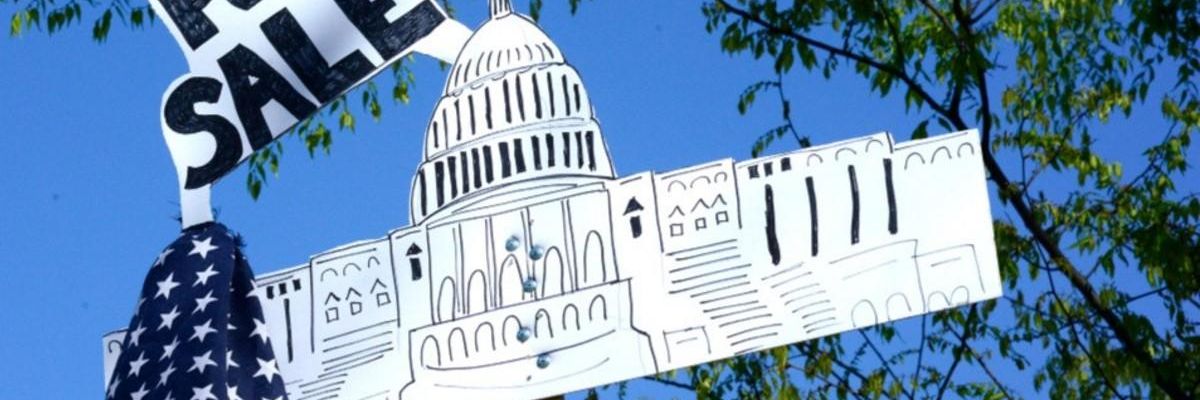

True, Western leaders encouraged the inflows. David Cameron, then UK Prime Minister, appealed in 2011 to a Moscow audience to "invest" in Britain. But it wasn't hard to convince the oligarchs to flood London with their money. Western countries' legislation prevents governments and the public not only from disturbing wealth stored in their jurisdictions but also from even knowing where and how much of it there is. Why else would countless corporations register in the US state of Delaware, using post office box addresses that guarantee their owners anonymity?

In fact, Western democracies grant foreign wealth even more protection from scrutiny. In a 2021 report aptly titled "The UK's Kleptocracy Problem," the London-based think tank Chatham House revealed that the golden visas for sale to oligarchs from all over the world were granted after "checks ... [that] were the sole responsibility of the law firms and wealth managers representing them." In my country, Greece, following our state's effective bankruptcy in 2010, an oligarch could buy a no-questions-asked golden visa, which also came with a Schengen visa (and the opportunity to live and travel anywhere in the European Union), for a measly EUR250,000 ($276,000). Similar visas are sold by other fiscally stressed eurozone countries, fueling a race to the bottom that the world's oligarchs greatly appreciate.

While there is good reason to focus on Russian money, now that Russian bombs are destroying Ukrainian cities, it is puzzling that only Russian billionaires are called oligarchs. Why is oligarchy, which means rule (arche) by the few (oligoi), considered an exclusively Russian phenomenon? Are the Saudi or Emirati princes not oligarchic? Do American billionaires, like those now flocking to buy Chelsea FC, smuggle less money out of their country than their Russian counterparts do, or have less political clout? Do they use such power better than the Russians?

Russia's wealthiest 0.01% (the top 1% of the top 1%) have taken about half their wealth, around $200 billion, out of Russia and stashed it in the UK and other havens. At the same time, America's wealthiest 0.01% have taken around $1.2 trillion out of the United States, principally to avoid paying taxes. So, in terms of magnitude, American plutocrats match every dollar that Russian plutocrats stash abroad to escape scrutiny with $10 of their own.

As for the relative political clout of Russian and American billionaires, it is not at all clear who has more. While there is no doubt that a number of Russian oligarchs have President Vladimir Putin's ear, he has more control over them than the American government has over its billionaires. Since the US Supreme Court's 2010 decision affording corporations the right to donate to politicians as if they were persons, America's richest 0.01% accounted for 40% of all campaign contributions. It has proved to be an excellent investment in wealth preservation.

Is it by chance that in the years since the "deregulation" of campaign financing, American billionaires have obtained the lowest tax rate in over a generation, and the lowest among all wealthy countries? Is it an accident that the US Internal Revenue Service is starved of resources? According to an authoritative empirical study of the US legislative record, none of this is an accident: the correlation between what Congress enacts and what most Americans prefer is not significantly greater than zero.

So, if non-Russian billionaires are also oligarchs, does the exclusive emphasis in the West on Russians mean that "our" oligarchs, and those nurtured by our allies, are in some sense better? Here we are treading on treacherous ethical ground.

To argue that the Saudi billionaires behind the decade-long devastation of Yemen are "better" than Abramovich is to invite mockery. Putin would feel vindicated if we dared claim that the American oilmen who reaped a windfall from the illegal US-UK invasion of Iraq were morally superior to the owners of Rosneft and Gazprom. To be sure, Putin's oligarchs turn a blind eye whenever a brave journalist is snuffed out in Russia. But, meanwhile, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange withers in a high-security UK prison, under conditions bordering on torture, for having exposed Western countries' war crimes following their illegal invasion of Iraq. And how did Western oligarchs and governments respond when their Saudi business partners dismembered the Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi?

Following Putin's invasion of Ukraine, the UK government declared its determination to rip away the veil of secrecy and deception shrouding the money parked in Britain to escape the scrutiny of law enforcement and tax authorities. Whether the reality matches the rhetoric remains to be seen. Already, there are signs of tension between the ambition to seize oligarchs' money and the imperative of keeping Britain "open for business."

Perhaps the only silver lining in the Ukrainian tragedy is that it has created an opportunity to scrutinize oligarchs not only with Russian passports but also their American, Saudi, Chinese, Indian, Nigerian, and, yes, Greek counterparts. An excellent place to start would be with the London mansions that Transparency International tells us sit empty. How about turning them over to refugees from Ukraine and Yemen? And, while we're at it, why not turn over Chelsea FC to its fans.