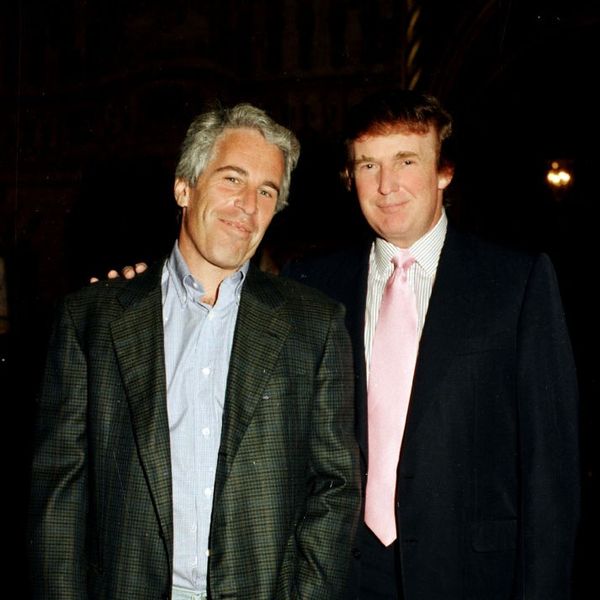

French far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen lays flowers at the Wall of the Disappeared, a memorial to colonists in Algeria, during a campaign stop in Perpignan, southern France, on April 8, 2022.

French Election Is Shaped by Legacy of Colonialism in Algeria: The Roots of Far-Right Le Pen

Right-wing presidential candidate Marine Le Pen's father volunteered to torture Algerian independence fighters, and her anti-immigration and anti-Muslim platform is inseparable from France's brutal colonization of the North African country.

Whether France is voting, commemorating D-day, or debating French identity in terms of Republic Values, Algeria is always present in some way. It is almost impossible to discuss anything of substance in France in which Algeria does not feature and, sometimes, dominate the debate. After all, Algeria was not just another d'outre-mer colony in North Africa whose independence in the 1960s failed to end all the emotional ties to its former colonizer, France. It is one of the few history cases in which the relationship between the former colony and its former colonizer has not been settled once and for all. It just lingers under the surface.

Almost all far-right policies in France appear to be related to Algeria's colonial years.

It will be a long time before France shakes off its Algerian legacy of brutality and atrocities.

Next July, Algiers will be celebrating 60 years of independence from France, while Paris, this Sunday 24 April, will be voting for its next president by choosing between incumbent Emmanuel Macron and his rival, Marine Le Pen, as the first round of voting failed to produce a conclusive winner. Algeria is present here, too.

In the first round of voting two weeks earlier, voters clearly rejected the traditional left and right that dominated French politics since Charles de Gaulle, in 1958, inaugurated the Fifth Republic. The French left, usually led by the Socialist Party and the traditional mainstream right, led by Le Republic, failed to score enough votes and was left to foot a huge expenses bill. To qualify for a state refund of half of its campaign expenses, it must win at least 5 percent of the votes. De Gaulle's heroic legacy is, in part, built on his Algerian connection.

This great rebuff by the French came after the left-leaning electorate voted for the far-left, while the far-right voted for a new boy in town, Eric Zemmour, who managed to cut through Marie Le Pen's traditional support, thus becoming the real far-right. His anti-immigration, anti-European, anti-Islam platform seemed to have worked, this time, in drawing away many of Ms. Le Pen's base voters.

Mr. Zemmour, who once described himself as "the blessed fruit of colonization," shares in the Algerian legacy as he is a descendent of an Algerian family who fled Algeria shortly before the brutal war of independence broke out in 1954. Millions of European settlers and Algerians, Harkis, who fought with France, fled Algeria and settled in France during and after the battle for Algeria. For Eric Zemmour to get over 7 percent of the vote in the first presidential round meant that the troubled French-Algerian past still sends its shadows over France.

Ms. Le Pen is also linked to Algeria. Her father, Jean Marie Le Pen, was a volunteer in the Algerian war heading a small unit of French intelligence in what is known as the "battle of Algiers." It is now confirmed that he was involved in carrying out atrocious torture techniques against Algerian fighters, including filling them with water to force confessions. Marine Le Pen expelled her father and renamed the party, but her anti-immigration policies and unfavorable anti-Muslim attitude are rooted in the Algerian experience.

France's far-right politics has been dotted with a long history of near fascist policies that have, over the years, become part of French mainstream politics. And almost all far-right policies in France appear to be related to Algeria's colonial years.

Centuries ago, France led the European rush of colonizing the rest of the world; it invaded Algeria, making it just another French colony, starting in 1830. However, within three decades, Algeria--a country that is more than four times the size of France--disappeared, giving way to what became known as "French Algeria", while most other French colonies were known, simply, as overseas territories or what the French call "d'outre-me" territories.

Instead, Algeria was integrated into mainland France more than 30 years before present-day Nice, a major city in the south of France, became French in 1860. Within fifty years after colonization, the department, "French Algeria," dominated the world wine market, despite the fact that Algeria is predominantly a Muslim country. It is estimated that after the 1930s, French Algeria was exporting some 1.5 billion liters of wine a year, mostly to ever-thirsty French consumers.

Official France and its army of European settlers never thought, let alone believed, that Algeria could become independent.

This in itself made France, and its more than a million European settlers, see Algeria as anything else but a French department, not a colony--not another country forcibly taken over.

French Algeria became part of France in every aspect, including in the way the French bureaucracy handled it. Almost all other colonies did not have this privilege. Official France and its army of European settlers never thought, let alone believed, that Algeria could become independent.

Algeria, at one point, became the jewel in the French "colonial throne," just as India became the jewel of the British Crown in 1858--28 years after Algeria deserved that nickname. Yet, such a description was never used in French history simply because Algeria, then, was seen as French--as Marseilles or Lille, rather than a colony.

Not accepting Algeria as a colony became part of the French colonial thinking, and it continues today by manifesting itself in different ways.

Emmanuel Macron, who is widely expected to narrowly win a second term, is the first French president to recognize some of the atrocities committed by France in Algeria, but failed to apologize. In 2021, his office rejected the idea of an apology simply because that would have been completely anti-established French colonial history which never considered Algeria anything but French. He is also credited with being the only French President to authorize an official history revisit by delegating the task to historian, Benjamin Stora.

Mr. Stora produced a report on France's conduct in colonized Algeria but the document, published in January 2021, did not recommend an apology. However, it is seen as a step forward towards a more self-searching French initiative to come to terms with that dark history. The report recommended establishing a "memory and truth commission" to determine the facts.

However, little has been done so far and, if anything is to happen, it has to wait until President Macron wins his second term in office on Sunday. Should Marine Le Pen win, she is likely to shelf the matter.

French people, across France, are constantly reminded of Algeria. Many streets and public places are named after infamous French war generals like General Thomas Bugeau, who was governor-general of Algeria in 1840, is given to an avenue in one of Paris's elegant neighborhoods. While the name Charles de Gaulle features in almost every square and avenue in every French town or city--he was the man who agreed to Algeria's independence. Names of Algerian independence heroes are, also, carried across Algeria today.

Algeria might not be, yet, the ghost in French public life but it will continue to dominate any serious French debate for a long time to come.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Whether France is voting, commemorating D-day, or debating French identity in terms of Republic Values, Algeria is always present in some way. It is almost impossible to discuss anything of substance in France in which Algeria does not feature and, sometimes, dominate the debate. After all, Algeria was not just another d'outre-mer colony in North Africa whose independence in the 1960s failed to end all the emotional ties to its former colonizer, France. It is one of the few history cases in which the relationship between the former colony and its former colonizer has not been settled once and for all. It just lingers under the surface.

Almost all far-right policies in France appear to be related to Algeria's colonial years.

It will be a long time before France shakes off its Algerian legacy of brutality and atrocities.

Next July, Algiers will be celebrating 60 years of independence from France, while Paris, this Sunday 24 April, will be voting for its next president by choosing between incumbent Emmanuel Macron and his rival, Marine Le Pen, as the first round of voting failed to produce a conclusive winner. Algeria is present here, too.

In the first round of voting two weeks earlier, voters clearly rejected the traditional left and right that dominated French politics since Charles de Gaulle, in 1958, inaugurated the Fifth Republic. The French left, usually led by the Socialist Party and the traditional mainstream right, led by Le Republic, failed to score enough votes and was left to foot a huge expenses bill. To qualify for a state refund of half of its campaign expenses, it must win at least 5 percent of the votes. De Gaulle's heroic legacy is, in part, built on his Algerian connection.

This great rebuff by the French came after the left-leaning electorate voted for the far-left, while the far-right voted for a new boy in town, Eric Zemmour, who managed to cut through Marie Le Pen's traditional support, thus becoming the real far-right. His anti-immigration, anti-European, anti-Islam platform seemed to have worked, this time, in drawing away many of Ms. Le Pen's base voters.

Mr. Zemmour, who once described himself as "the blessed fruit of colonization," shares in the Algerian legacy as he is a descendent of an Algerian family who fled Algeria shortly before the brutal war of independence broke out in 1954. Millions of European settlers and Algerians, Harkis, who fought with France, fled Algeria and settled in France during and after the battle for Algeria. For Eric Zemmour to get over 7 percent of the vote in the first presidential round meant that the troubled French-Algerian past still sends its shadows over France.

Ms. Le Pen is also linked to Algeria. Her father, Jean Marie Le Pen, was a volunteer in the Algerian war heading a small unit of French intelligence in what is known as the "battle of Algiers." It is now confirmed that he was involved in carrying out atrocious torture techniques against Algerian fighters, including filling them with water to force confessions. Marine Le Pen expelled her father and renamed the party, but her anti-immigration policies and unfavorable anti-Muslim attitude are rooted in the Algerian experience.

France's far-right politics has been dotted with a long history of near fascist policies that have, over the years, become part of French mainstream politics. And almost all far-right policies in France appear to be related to Algeria's colonial years.

Centuries ago, France led the European rush of colonizing the rest of the world; it invaded Algeria, making it just another French colony, starting in 1830. However, within three decades, Algeria--a country that is more than four times the size of France--disappeared, giving way to what became known as "French Algeria", while most other French colonies were known, simply, as overseas territories or what the French call "d'outre-me" territories.

Instead, Algeria was integrated into mainland France more than 30 years before present-day Nice, a major city in the south of France, became French in 1860. Within fifty years after colonization, the department, "French Algeria," dominated the world wine market, despite the fact that Algeria is predominantly a Muslim country. It is estimated that after the 1930s, French Algeria was exporting some 1.5 billion liters of wine a year, mostly to ever-thirsty French consumers.

Official France and its army of European settlers never thought, let alone believed, that Algeria could become independent.

This in itself made France, and its more than a million European settlers, see Algeria as anything else but a French department, not a colony--not another country forcibly taken over.

French Algeria became part of France in every aspect, including in the way the French bureaucracy handled it. Almost all other colonies did not have this privilege. Official France and its army of European settlers never thought, let alone believed, that Algeria could become independent.

Algeria, at one point, became the jewel in the French "colonial throne," just as India became the jewel of the British Crown in 1858--28 years after Algeria deserved that nickname. Yet, such a description was never used in French history simply because Algeria, then, was seen as French--as Marseilles or Lille, rather than a colony.

Not accepting Algeria as a colony became part of the French colonial thinking, and it continues today by manifesting itself in different ways.

Emmanuel Macron, who is widely expected to narrowly win a second term, is the first French president to recognize some of the atrocities committed by France in Algeria, but failed to apologize. In 2021, his office rejected the idea of an apology simply because that would have been completely anti-established French colonial history which never considered Algeria anything but French. He is also credited with being the only French President to authorize an official history revisit by delegating the task to historian, Benjamin Stora.

Mr. Stora produced a report on France's conduct in colonized Algeria but the document, published in January 2021, did not recommend an apology. However, it is seen as a step forward towards a more self-searching French initiative to come to terms with that dark history. The report recommended establishing a "memory and truth commission" to determine the facts.

However, little has been done so far and, if anything is to happen, it has to wait until President Macron wins his second term in office on Sunday. Should Marine Le Pen win, she is likely to shelf the matter.

French people, across France, are constantly reminded of Algeria. Many streets and public places are named after infamous French war generals like General Thomas Bugeau, who was governor-general of Algeria in 1840, is given to an avenue in one of Paris's elegant neighborhoods. While the name Charles de Gaulle features in almost every square and avenue in every French town or city--he was the man who agreed to Algeria's independence. Names of Algerian independence heroes are, also, carried across Algeria today.

Algeria might not be, yet, the ghost in French public life but it will continue to dominate any serious French debate for a long time to come.

Whether France is voting, commemorating D-day, or debating French identity in terms of Republic Values, Algeria is always present in some way. It is almost impossible to discuss anything of substance in France in which Algeria does not feature and, sometimes, dominate the debate. After all, Algeria was not just another d'outre-mer colony in North Africa whose independence in the 1960s failed to end all the emotional ties to its former colonizer, France. It is one of the few history cases in which the relationship between the former colony and its former colonizer has not been settled once and for all. It just lingers under the surface.

Almost all far-right policies in France appear to be related to Algeria's colonial years.

It will be a long time before France shakes off its Algerian legacy of brutality and atrocities.

Next July, Algiers will be celebrating 60 years of independence from France, while Paris, this Sunday 24 April, will be voting for its next president by choosing between incumbent Emmanuel Macron and his rival, Marine Le Pen, as the first round of voting failed to produce a conclusive winner. Algeria is present here, too.

In the first round of voting two weeks earlier, voters clearly rejected the traditional left and right that dominated French politics since Charles de Gaulle, in 1958, inaugurated the Fifth Republic. The French left, usually led by the Socialist Party and the traditional mainstream right, led by Le Republic, failed to score enough votes and was left to foot a huge expenses bill. To qualify for a state refund of half of its campaign expenses, it must win at least 5 percent of the votes. De Gaulle's heroic legacy is, in part, built on his Algerian connection.

This great rebuff by the French came after the left-leaning electorate voted for the far-left, while the far-right voted for a new boy in town, Eric Zemmour, who managed to cut through Marie Le Pen's traditional support, thus becoming the real far-right. His anti-immigration, anti-European, anti-Islam platform seemed to have worked, this time, in drawing away many of Ms. Le Pen's base voters.

Mr. Zemmour, who once described himself as "the blessed fruit of colonization," shares in the Algerian legacy as he is a descendent of an Algerian family who fled Algeria shortly before the brutal war of independence broke out in 1954. Millions of European settlers and Algerians, Harkis, who fought with France, fled Algeria and settled in France during and after the battle for Algeria. For Eric Zemmour to get over 7 percent of the vote in the first presidential round meant that the troubled French-Algerian past still sends its shadows over France.

Ms. Le Pen is also linked to Algeria. Her father, Jean Marie Le Pen, was a volunteer in the Algerian war heading a small unit of French intelligence in what is known as the "battle of Algiers." It is now confirmed that he was involved in carrying out atrocious torture techniques against Algerian fighters, including filling them with water to force confessions. Marine Le Pen expelled her father and renamed the party, but her anti-immigration policies and unfavorable anti-Muslim attitude are rooted in the Algerian experience.

France's far-right politics has been dotted with a long history of near fascist policies that have, over the years, become part of French mainstream politics. And almost all far-right policies in France appear to be related to Algeria's colonial years.

Centuries ago, France led the European rush of colonizing the rest of the world; it invaded Algeria, making it just another French colony, starting in 1830. However, within three decades, Algeria--a country that is more than four times the size of France--disappeared, giving way to what became known as "French Algeria", while most other French colonies were known, simply, as overseas territories or what the French call "d'outre-me" territories.

Instead, Algeria was integrated into mainland France more than 30 years before present-day Nice, a major city in the south of France, became French in 1860. Within fifty years after colonization, the department, "French Algeria," dominated the world wine market, despite the fact that Algeria is predominantly a Muslim country. It is estimated that after the 1930s, French Algeria was exporting some 1.5 billion liters of wine a year, mostly to ever-thirsty French consumers.

Official France and its army of European settlers never thought, let alone believed, that Algeria could become independent.

This in itself made France, and its more than a million European settlers, see Algeria as anything else but a French department, not a colony--not another country forcibly taken over.

French Algeria became part of France in every aspect, including in the way the French bureaucracy handled it. Almost all other colonies did not have this privilege. Official France and its army of European settlers never thought, let alone believed, that Algeria could become independent.

Algeria, at one point, became the jewel in the French "colonial throne," just as India became the jewel of the British Crown in 1858--28 years after Algeria deserved that nickname. Yet, such a description was never used in French history simply because Algeria, then, was seen as French--as Marseilles or Lille, rather than a colony.

Not accepting Algeria as a colony became part of the French colonial thinking, and it continues today by manifesting itself in different ways.

Emmanuel Macron, who is widely expected to narrowly win a second term, is the first French president to recognize some of the atrocities committed by France in Algeria, but failed to apologize. In 2021, his office rejected the idea of an apology simply because that would have been completely anti-established French colonial history which never considered Algeria anything but French. He is also credited with being the only French President to authorize an official history revisit by delegating the task to historian, Benjamin Stora.

Mr. Stora produced a report on France's conduct in colonized Algeria but the document, published in January 2021, did not recommend an apology. However, it is seen as a step forward towards a more self-searching French initiative to come to terms with that dark history. The report recommended establishing a "memory and truth commission" to determine the facts.

However, little has been done so far and, if anything is to happen, it has to wait until President Macron wins his second term in office on Sunday. Should Marine Le Pen win, she is likely to shelf the matter.

French people, across France, are constantly reminded of Algeria. Many streets and public places are named after infamous French war generals like General Thomas Bugeau, who was governor-general of Algeria in 1840, is given to an avenue in one of Paris's elegant neighborhoods. While the name Charles de Gaulle features in almost every square and avenue in every French town or city--he was the man who agreed to Algeria's independence. Names of Algerian independence heroes are, also, carried across Algeria today.

Algeria might not be, yet, the ghost in French public life but it will continue to dominate any serious French debate for a long time to come.