A global wheat crisis has been caused by Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing war there, which has drastically reduced Ukraine's wheat production and exports, while the resultant international sanctions have also somewhat reduced Russian production. Now, there is yet another complication, as the fertile wheat-growing regions of North India have been hit with drought and a severe heatwave. Young wheat plants don't do well with extreme heat. So the wheat crisis just got worse. India is the world's second-largest wheat producer. While it exports little, using the crops to feed its 1.3 billion people, it will now have to import to make up for the loss, increasing demand at a time of shrinking supply.

Oil is behind both catastrophes, war and the climate disaster.

While India has a hot climate and heat waves have struck it before, this time it is different. India hasn't seen anything like the temperatures in March for at least a century and a quarter, and probably not for millennia. Global temperatures were cooler before we began pumping billions of tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere with the Industrial Revolution. This heatwave is part of the global climate emergency.

India's governments--first the colonial British and since 1947 the independent state--have been keeping temperature records all over the country for at least 122 years. 2022 is crashing through many previous records. This was the hottest March since records began being kept.

Aniruddha Gosal at AP notes that a Lancet report last year found that India's vulnerability to extreme heat increased 15% from 1990 to 2019. India and Brazil are the two countries where most people die annually of heat exposure.

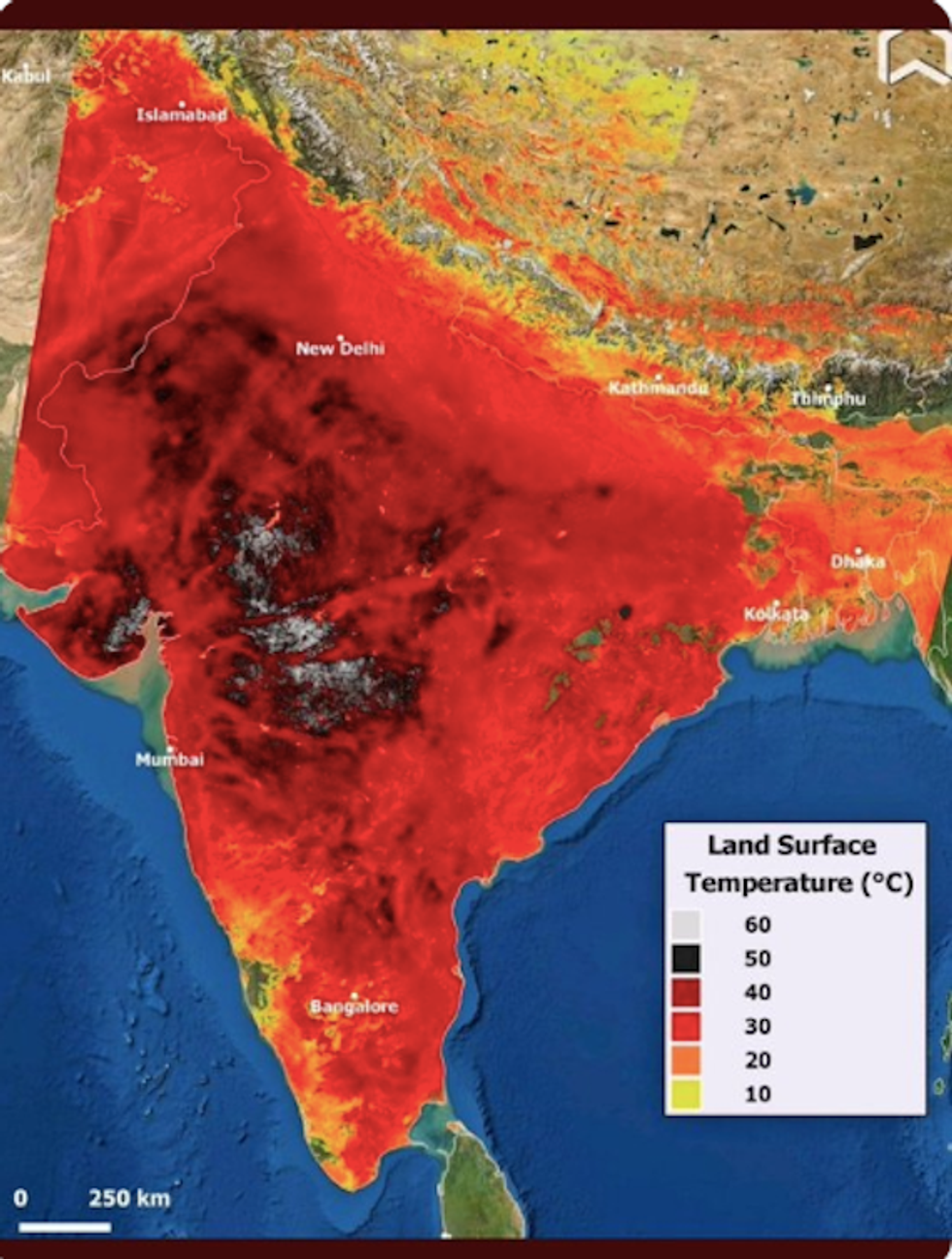

Temperatures across India on April 30 are shown in Celsius. 45degC is about 113degF. (Image: Twitter)

A recent article by Mariam Zachariah et al. in Geophysical Research Letters finds that:

The three states of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh in the Indo-Gangetic Plains are the largest wheat producers in India, playing a crucial role in ensuring food security of this densely populated country. Wheat, a winter crop, is reported to be sensitive to heat stress because of rising temperatures and climate change. However, in previous studies, the sensitivity of wheat yield has been mainly explored with respect to the magnitude of temperature. Here, based on statistical analysis of observed temperature and actual wheat production data, we show that the magnitude, frequency, and areal extent of agricultural heat stress events are increasing in India's wheat belt, with frequency showing the most pronounced trend... Under climate change, chances of below-average wheat production rise by 8%-27% in the worst-case scenario."

So the authors are saying that high-powered modeling shows that not only increased average temperatures in India but also more frequent extreme heatwaves have the potential of reducing wheat yields by as much as 27%. They say this is a worst-case scenario, but at the moment we are heading for the worst case scenario of the climate emergency, since nobody is significantly reducing their carbon dioxide emissions, which jumped up last year.

I've lived in India in March and April, and I remember them as blisteringly hot. Admittedly, June before the monsoon rains come is the worst. Even once the rains come, it is still torrid, but you get a little relief until the heat begins subsiding in September. My experiences in India were as a student, so I didn't have air conditioning, and it was a long time ago, when most people there didn't because of the expense. Evaporative or "desert" coolers, which blew air through water and straw, were popular in the hot dry months before the monsoon, though I never felt they did a very good job.

But in the succeeding 40 years, things have changed for the worse, as average global surface temperatures rise because we are burning gasoline, methane gas, and petroleum, which are greenhouse gases that keep the sun's heat from radiating back into space. That is stupid of us, just as stupid as fighting wars over territory that we are making worthless by wrecking the Earth. Oil is behind both catastrophes, war and the climate disaster.