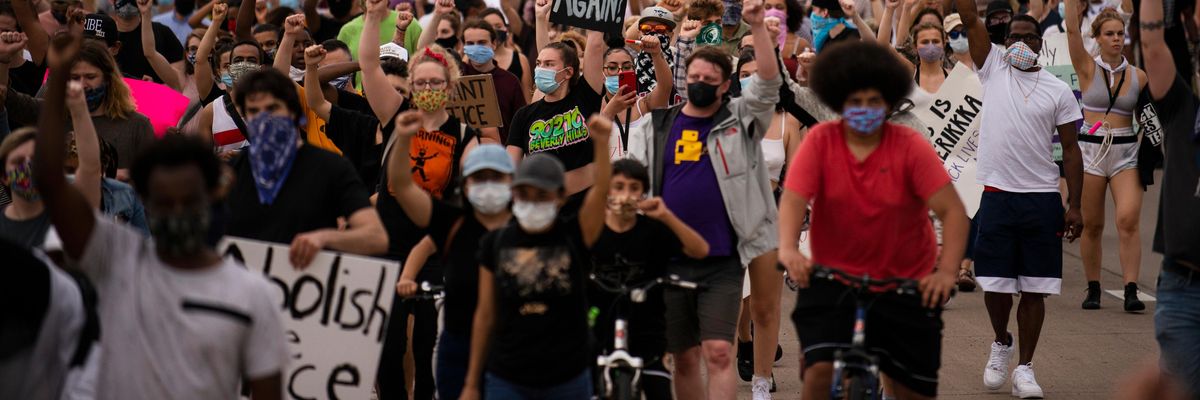

Two years ago, mass protests in the wake of George Floyd's murder by Minneapolis police galvanized Americans to confront the disparate impact that a broken system of policing, arrest and incarceration had on Black and Brown communities. For the first time in a generation, nearly all Americans favored change to the criminal justice system. Today, it looks like the pendulum has swung away from reform. Police budgets have mostly grown--even in Biden's federal budget--but conservatives blame "defunding" and reform prosecutors for rises in crime.

Has the reform movement failed? On the contrary: it's hardly even been tried.

Local governments have yet to make the necessary investments in alternatives to incarceration that can create a lasting link between renewed justice and safety and reform measures. Meanwhile, anti-reform voices have defined reform as a terrifying absence of action. They tell a story about progressive prosecutors who won't use gang enhancements, judges who won't set cash bail, and (without evidence) local governments who defund the police. We understand this as stopping harm. They talk about it like it's unilateral disarmament.

I understand the importance of laying down the tools of mass incarceration. As a teenager, I saw up close the harm that they do. My own baby brother was churned through this system, suffering trauma when he needed help. As the leader of a social justice foundation in Los Angeles, I see its effects on the communities we work with.

But a story about what we should stop doing cannot inspire hope or vanquish fear. Instead, we need to talk about the positive actions that complement criminal justice reform.

It would be a tragedy if we doubled down on more police and more punishment before we've even tried reform.

And there, we are in luck. Because in Los Angeles, as in many of the communities where reform is under attack, there are many. They've been overlooked in the premature obituaries for reform. Call them alternatives to incarceration at the community level.

Even partially implemented, they're showing results. Los Angeles has too often been a laboratory for the worst approaches to policing and prosecution before launching them nationwide. Decades of activism have reversed that momentum, seeding experiments in restorative justice and early intervention. Years of work are paying off in legislation and funded programs that are changing lives.

In 2019, LA County's groundbreaking Alternatives to Incarceration report drew a roadmap for moving from a system of punishment to one built upon care and services by "minimizing contact with law enforcement and directing people to health services instead of jail." In 2020, the Youth Justice Reimagined report pushed this vision even farther, proposing to fully dismantle the detention and probation system that locked young people up, replacing it with a new Department of Youth Development that would emphasize therapeutic, age-appropriate treatment in the communities where young people live instead of uprooting them and sending them to harsh facilities, miles from the people who care about them. Research shows that these programs actually prevent crime and make us all safer, whereas punishment and incarceration increase recidivism, and make us less safe.

The results we have seen are nothing short of transformative. Consider the story of Ezekiel, who had a life sentence commuted because of a 2016 measure that allowed judicial discretion over youth sentencing. Returning home to Los Angeles, he received one-on-one counseling support, mentorship, and housing through the Anti-Recidivism Coalition (ARC). Today, he is a youth leader on policy issues around youth criminal justice. Or take Tommy: incarcerated as a juvenile, he found employment in the construction sector with the support of ARC, and pivoted towards mentorship as a vocation. He now works as a program associate at the foundation I lead, where he is working to transform the system that thankfully did not derail his life permanently.

Even more compelling are the stories we don't hear--the vast number of youth who, following diversion, never face law enforcement again. One study measured diversion programs as 2.5 times better at preventing recidivism than jail or prison.

These real successes make it possible to fulfill the promise of the protests. We can reduce the harm created by the system by curtailing cash bail, ending sentencing enhancements, and stopping prosecution of low-level misdemeanors. But it will require growing the infrastructure of community-based care to reduce violence and to create true public safety through mental health support, housing, and other social services. They will only succeed with the investment of resources and time. And rolling back either prematurely will turn a fear of rising crime into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Research supports this entire agenda. Mass incarceration and violent over-policing have failed. Their effects are horrifyingly racist. They don't reduce crime; they do perpetuate trauma. Meanwhile, the success of youth diversion, to take one example, is matched by services and housing for adults. A study by the RAND Corporation found that 86% of participants removed from jail into LA County's Office of Diversion and Reentry Housing program had no new felony convictions, despite a high prevalence of factors such as mental health and substance use disorders.

Here in Los Angeles, these programs have yet to reach their full potential. They need funding and staffing, and will need years of consistent political support to undo the damage of the disaster that preceded them. Many aspects are still in the too-often-neglected implementation stage and will only succeed if the people who suffered the abuses of heavy-handed policing and disproportionate jailing keep their seats at the table and ensure that these resources go where they are most needed.

It would be a tragedy if we doubled down on more police and more punishment before we've even tried reform. The voices of paranoia and fear want you to think that reformers ending harmful policies creates a vacuum where violence rises. The fact is, the communities most affected by persistent violence, poverty, and over-policing have created alternatives to incarceration that will replace that vacuum with safer, healthier cities. Let's build them together.