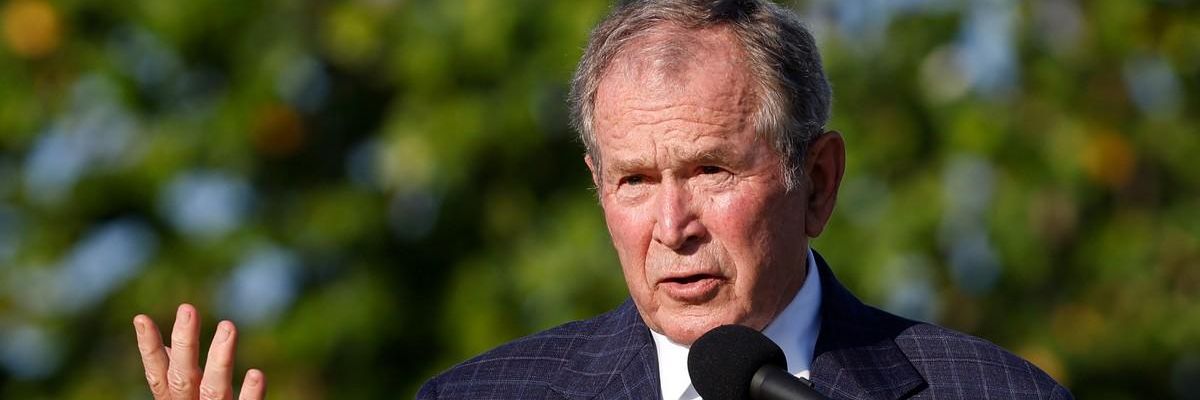

In 2004, high-ranking staffers in the George W. Bush administration spearheaded a holistic review of the president's emergency powers. Their goal was to refresh a set of secret plans known as "presidential emergency action documents," or PEADs, the continuity-of-government playbook that emerged under President Dwight Eisenhower as a response to the threat of nuclear war.

We have been left to wonder whether existing documents still green-light the violation of Americans' constitutional rights and civil liberties, or if modern sensibilities and understandings of the law have moderated their approach.

Those documents had been revised previously, but they took on new significance in the wake of 9/11. Their review was, as one Bush official saw it, an "urgent and compelling security effort, especially in light of ongoing threats."

In response to Freedom of Information Act requests, the George W. Bush Presidential Library turned over to the Brennan Center more than 500 pages generated during this review and subsequent reviews in 2006 and 2008. (Another 6,000 pages were withheld in full because they are classified.) The released records shed troubling new light on the powers that modern presidents claim they possess in moments of crisis--powers that appear to lack oversight from Congress, the courts, or the public.

Origins

Faced with the possibility of a Soviet nuclear strike, mid- to late-20th-century presidents crafted a collection of pre-planned emergency actions. Although none has ever been leaked, declassified, or deployed, we know that some early drafts rested on broad claims to inherent executive power. Official reports from the 1960s indicate that various PEADs authorized the president to suspend habeas corpus, detain "dangerous persons" within the United States, censor news media, and prevent international travel. (The Brennan Center's repository of related materials, spanning the administrations of 12 presidents, can be found here.)

Beyond that period, however, our knowledge of PEADs' content fades. We have been left to wonder whether existing documents still green-light the violation of Americans' constitutional rights and civil liberties, or if modern sensibilities and understandings of the law have moderated their approach.

Equipped with the latest tranche of presidential records, we now know that at least some of the most disturbing aspects of early-Cold War emergency action documents persisted as of 2008. Although the library withheld almost all substantive information about the PEADs under review, we have been able to reconstruct the broad contours of several of them.

Controlling communications

At least one of the documents under review was designed to implement the emergency authorities contained in Section 706 of the Communications Act. During World War II, Congress granted the president authority to shut down or seize control of "any facility or station for wire communication" upon proclamation "that there exists a state or threat of war involving the United States."

This frighteningly expansive language was, at the time, hemmed in by Americans' limited use of telephone calls and telegrams. Today, however, a president willing to test the limits of his or her authority might interpret "wire communications" to encompass the internet--and therefore claim a "kill switch" over vast swaths of electronic communication.

And indeed, Bush administration officials repeatedly highlighted the statute's flexibility: it was "very broad," as one official in the National Security Council scribbled, and it extended "broader than common carriers in FCC [Federal Communications Commission] juris[diction]."

Previously, it was a matter of speculation as to whether any emergency action documents purported to implement this authority. But Bush officials evidently examined at least one such document as part of their review, a Communications Act PEAD that appears to have predated the administration. And the library's records suggest that the administration added three more documents on the same subject.

Detention authority

The records indicate that at least one presidential emergency action document pertained to the suspension of habeas corpus. An internal memorandum from June 2008 specified that a document under the Justice Department's jurisdiction was "[s]till being revised by OLC [Office of Legal Counsel], in light of recent Supreme Court opinion." Examining the Court's rulings over the previous months, it is evident that this must refer to the landmark decision in Boumediene v. Bush, which recognized Guantanamo Bay prisoners' constitutional right to challenge their detention in court. This strongly suggests that the early-Cold War PEADs purporting to suspend habeas corpus had survived, at least in some form, and were part of the Bush administration's review.

The result of the administration's post-Boumediene revision is unknown. Significantly, though, it doesn't appear that any emergency action documents were withdrawn or cancelled. To the contrary, eight PEADs were added, bringing the total number to 56.

Inhibiting the right to travel

Restricting the use of U.S. passports--a reported feature of some early presidential emergency action documents--remained on the table as of 2008. Records generated by the Bush administration's review highlighted a provision of law from 1978 that allows the government to curtail international movement based on "war," "armed hostilities," or "imminent danger to the public health or the physical safety of United States travellers."

Although presidents have used this statute to ban travel to Lebanon, Iraq, Libya, and North Korea, a more sweeping abrogation of the right to travel would represent a stark break from modern historical practice.

Triggering other emergency powers

The national emergency declared after 9/11 -- which is still in effect today and continues to prop up the United States' military presence across the globe--was cited in connection with one or more PEADs.

A national emergency declaration unlocks enhanced authorities contained in more than 120 provisions of law. Bush invoked several such authorities, but several dozen others were--and still are--available to the president as a result of Proclamation 7463. Presumably, the reference to the proclamation during the administration's review implies the existence of documents designed to implement other statutory emergency powers, which run the gamut from anodyne to alarming, nearly four years after the attacks.

As with any archival expedition, the silences are often the most telling. William Arkin, a noted expert on PEADs, reviewed the new materials disclosed by the library and observed that they relate primarily to civil agencies--few, if any, touch on the role of the military in times of crisis. He suggests that this "black side" would have been discussed at a higher level of classification. By implication, the most daring claims to presidential power may have been entirely excluded from this tranche of documents.

Also missing from the records is any evidence that the Bush administration communicated--much less collaborated--with Congress during its review. We have previously noted that presidents have kept PEADs secret, not only from the American public but from lawmakers as well. This lack of disclosure effectively blocks a coequal branch of government from overseeing emergency protocols.

With Congress unable to serve its constitutional role as a check on the executive branch, there remains the possibility that modern PEADs, like their historical predecessors, sacrifice Americans' constitutional rights and the rule of law in the name of emergency planning. Congress should pass Sen. Ed Markey's REIGN Act, which has been incorporated into the Protecting Our Democracy Act and the National Security Reforms and Accountability Act, to bring these shadowy powers to account.