SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

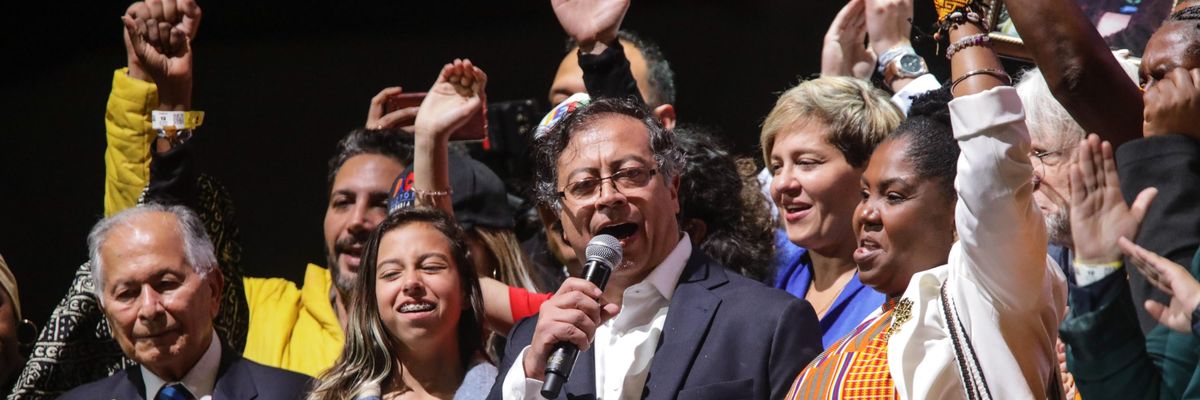

Gustavo Petro, the leftist former mayor of Bogota, celebrates in Bogota after winning Colombia's presidential election on June 19, 2022. (Photo: Juancho Torres/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

The Amazon rainforest, our scientists tell us, essentially works as our world's lungs. If those Amazonian lungs ever stop breathing, so will we.

The Amazon rainforest will never be safe as long as the key nations of the Amazon basin remain so unequal.

This simple relationship just may make Gustavo Petro, the newly elected progressive president of Colombia, one of our planet's most significant heads of state. If he succeeds over the next four years, the Amazon has a shot at survival--and so do the rest of us.

Petro and his environmental activist running mate Francia Marquez have pledged to work with their fellow progressive Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the odds-on favorite to win Brazil's presidential race this coming October, to save the Amazon rainforest. With leadership from Petro and Marquez, that effort may well succeed. Both these veteran activists deeply understand the core reality--economic inequality--that's left the Amazon rainforest so catastrophically vulnerable.

Colombia currently rates as the world's second-most unequal major nation by income, notes a World Bank report published this past fall. The only major nation more unequal than Colombia: Brazil.

Colombia's richest 10 percent are now taking in 11 times the income of the nation's poorest 10 percent, the World Bank details. In the Slovak Republic, by income our globe's most equal nation, the top 10 percent only average triple the income of the poorest 10 percent.

The control over Colombia's land mass tells an even more top-heavy story. The nation's top 1 percent of private landholders own 81 percent of Colombia's acreage.

Taxes in Colombia do precious little to alter this striking maldistribution of income and wealth. The nation's personal income tax only kicks in at about four times Colombia's median income, a rate structure, the World Bank points out, that leaves most all of Colombia's rich paying no more than 10 percent of their actual total income in tax.

Colombia's social welfare programs, meanwhile, "suffer from large leakages to high-income households," and the nation's public pension system generates "subsides that accrue mostly to recipients of high pensions."

Dynamics like these have left Colombia's inequality the world's most entrenched. No nation scores worst on the "intergenerational persistence of earnings," a tag researchers use when they compare what parents earn to what their kids end up making. In a nation with persistently unequal earnings, parents who make over five times what average parents make will have children who make over five times average earnings.

Last fall's World Bank analysis of Colombia's deep-seated inequalities argues that reducing those inequalities makes eminent sense on both moral and economic grounds. Greater equality in Colombia, the World Bank analysts stress, would boost growth and promote social cohesion.

What these analysts don't stress: Greater equality in Colombia would also help save the Earth. The Amazon rainforest will never be safe as long as the key nations of the Amazon basin remain so unequal.

The increasingly concentrated ownership of Colombia's best agricultural land is driving poor farming families ever deeper into the rainforest.

Why does inequality in Colombia matter so much to our climate future? The increasingly concentrated ownership of Colombia's best agricultural land is driving poor farming families ever deeper into the rainforest. That same concentration has created a labor force desperate enough to take jobs with hustlers getting rich off of cattle-ranching, logging, and various other assaults on the rainforest.

Past presidents of Colombia could have, of course, addressed this desperation with programs to help the nation's most destitute. But paying for those programs would have required higher taxes on Colombia's most affluent, and, until this year, these affluents haven't had to face that particular prospect in quite some time.

In fact, the rich in Colombia haven't faced a national leader interested in seriously taxing them since Jorge Eliecer Gaitan Ayala--the last serious progressive candidate for Colombia's top office before Preto--died in a broad-daylight assassination during his 1948 presidential campaign.

Gustavo Petro and Francia Marquez will now be taking office after running on a platform that places the well-being of Colombia's poor and our global climate above the interests of the affluents who've dominated Colombia for so long. Their proposed agrarian reforms will guarantee rural families the right to land. Petro and Marquez have also pledged to phase out fossil fuels--including oil, Colombia's current top export--and protect their nation's incredibly rich biodiversity, one of the world's most expansive.

On taxes, the Petro government will be upping the ask on Colombia's "4,000 largest fortunes." Petro's initial prime targets include the dividend income that currently goes largely untaxed and wealth transfers abroad. Preto is promising, for instance, to deny government resources to individuals who maintain financial accounts in "tax haven" nations.

"Transfers abroad," notes Nick Corbishley, a British analyst who's traveled widely in South America, "make for an interesting target, given the propensity for wealthy Latin American businesses and families to move their money overseas, particularly to Miami, whenever a government of even mild left-wing persuasion comes into power."

Opposition from the affluent to Preto's environmental and equity agenda has, predictably, already begun to congeal.

"Petro's critics fear that his ambitious plans, including his redistributive policies and his proposal to ban new oil exploration, could ruin Colombia's economy," observes the Washington Post's Samantha Schmidt.

A good many Colombians, Schmidt reminds us, are already experiencing a ruined economy. Almost half of all Colombians are currently "experiencing some type of poverty and struggle to find enough to eat."

Yet Preto's critics, the Post analyst adds, can only see Preto's interest in declaring "an economic state of emergency to combat hunger" as evidence of "his willingness to work around democratic institutions to push through his agenda."

This sort of bogus "concern" for the rule of law has in the past regularly greased the skids for U.S. interventions that have helped topple left-leaning governments in Latin America that have refused to genuflect before their traditional national elites.

But those traditional elites have never faced the broad challenge they face now. If Lula takes the Brazilian presidency this fall, as polls indicate he will, progressives like Preto will be running Latin America's six largest nations.

The Amazon is cheering. We should be too.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The Amazon rainforest, our scientists tell us, essentially works as our world's lungs. If those Amazonian lungs ever stop breathing, so will we.

The Amazon rainforest will never be safe as long as the key nations of the Amazon basin remain so unequal.

This simple relationship just may make Gustavo Petro, the newly elected progressive president of Colombia, one of our planet's most significant heads of state. If he succeeds over the next four years, the Amazon has a shot at survival--and so do the rest of us.

Petro and his environmental activist running mate Francia Marquez have pledged to work with their fellow progressive Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the odds-on favorite to win Brazil's presidential race this coming October, to save the Amazon rainforest. With leadership from Petro and Marquez, that effort may well succeed. Both these veteran activists deeply understand the core reality--economic inequality--that's left the Amazon rainforest so catastrophically vulnerable.

Colombia currently rates as the world's second-most unequal major nation by income, notes a World Bank report published this past fall. The only major nation more unequal than Colombia: Brazil.

Colombia's richest 10 percent are now taking in 11 times the income of the nation's poorest 10 percent, the World Bank details. In the Slovak Republic, by income our globe's most equal nation, the top 10 percent only average triple the income of the poorest 10 percent.

The control over Colombia's land mass tells an even more top-heavy story. The nation's top 1 percent of private landholders own 81 percent of Colombia's acreage.

Taxes in Colombia do precious little to alter this striking maldistribution of income and wealth. The nation's personal income tax only kicks in at about four times Colombia's median income, a rate structure, the World Bank points out, that leaves most all of Colombia's rich paying no more than 10 percent of their actual total income in tax.

Colombia's social welfare programs, meanwhile, "suffer from large leakages to high-income households," and the nation's public pension system generates "subsides that accrue mostly to recipients of high pensions."

Dynamics like these have left Colombia's inequality the world's most entrenched. No nation scores worst on the "intergenerational persistence of earnings," a tag researchers use when they compare what parents earn to what their kids end up making. In a nation with persistently unequal earnings, parents who make over five times what average parents make will have children who make over five times average earnings.

Last fall's World Bank analysis of Colombia's deep-seated inequalities argues that reducing those inequalities makes eminent sense on both moral and economic grounds. Greater equality in Colombia, the World Bank analysts stress, would boost growth and promote social cohesion.

What these analysts don't stress: Greater equality in Colombia would also help save the Earth. The Amazon rainforest will never be safe as long as the key nations of the Amazon basin remain so unequal.

The increasingly concentrated ownership of Colombia's best agricultural land is driving poor farming families ever deeper into the rainforest.

Why does inequality in Colombia matter so much to our climate future? The increasingly concentrated ownership of Colombia's best agricultural land is driving poor farming families ever deeper into the rainforest. That same concentration has created a labor force desperate enough to take jobs with hustlers getting rich off of cattle-ranching, logging, and various other assaults on the rainforest.

Past presidents of Colombia could have, of course, addressed this desperation with programs to help the nation's most destitute. But paying for those programs would have required higher taxes on Colombia's most affluent, and, until this year, these affluents haven't had to face that particular prospect in quite some time.

In fact, the rich in Colombia haven't faced a national leader interested in seriously taxing them since Jorge Eliecer Gaitan Ayala--the last serious progressive candidate for Colombia's top office before Preto--died in a broad-daylight assassination during his 1948 presidential campaign.

Gustavo Petro and Francia Marquez will now be taking office after running on a platform that places the well-being of Colombia's poor and our global climate above the interests of the affluents who've dominated Colombia for so long. Their proposed agrarian reforms will guarantee rural families the right to land. Petro and Marquez have also pledged to phase out fossil fuels--including oil, Colombia's current top export--and protect their nation's incredibly rich biodiversity, one of the world's most expansive.

On taxes, the Petro government will be upping the ask on Colombia's "4,000 largest fortunes." Petro's initial prime targets include the dividend income that currently goes largely untaxed and wealth transfers abroad. Preto is promising, for instance, to deny government resources to individuals who maintain financial accounts in "tax haven" nations.

"Transfers abroad," notes Nick Corbishley, a British analyst who's traveled widely in South America, "make for an interesting target, given the propensity for wealthy Latin American businesses and families to move their money overseas, particularly to Miami, whenever a government of even mild left-wing persuasion comes into power."

Opposition from the affluent to Preto's environmental and equity agenda has, predictably, already begun to congeal.

"Petro's critics fear that his ambitious plans, including his redistributive policies and his proposal to ban new oil exploration, could ruin Colombia's economy," observes the Washington Post's Samantha Schmidt.

A good many Colombians, Schmidt reminds us, are already experiencing a ruined economy. Almost half of all Colombians are currently "experiencing some type of poverty and struggle to find enough to eat."

Yet Preto's critics, the Post analyst adds, can only see Preto's interest in declaring "an economic state of emergency to combat hunger" as evidence of "his willingness to work around democratic institutions to push through his agenda."

This sort of bogus "concern" for the rule of law has in the past regularly greased the skids for U.S. interventions that have helped topple left-leaning governments in Latin America that have refused to genuflect before their traditional national elites.

But those traditional elites have never faced the broad challenge they face now. If Lula takes the Brazilian presidency this fall, as polls indicate he will, progressives like Preto will be running Latin America's six largest nations.

The Amazon is cheering. We should be too.

The Amazon rainforest, our scientists tell us, essentially works as our world's lungs. If those Amazonian lungs ever stop breathing, so will we.

The Amazon rainforest will never be safe as long as the key nations of the Amazon basin remain so unequal.

This simple relationship just may make Gustavo Petro, the newly elected progressive president of Colombia, one of our planet's most significant heads of state. If he succeeds over the next four years, the Amazon has a shot at survival--and so do the rest of us.

Petro and his environmental activist running mate Francia Marquez have pledged to work with their fellow progressive Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, the odds-on favorite to win Brazil's presidential race this coming October, to save the Amazon rainforest. With leadership from Petro and Marquez, that effort may well succeed. Both these veteran activists deeply understand the core reality--economic inequality--that's left the Amazon rainforest so catastrophically vulnerable.

Colombia currently rates as the world's second-most unequal major nation by income, notes a World Bank report published this past fall. The only major nation more unequal than Colombia: Brazil.

Colombia's richest 10 percent are now taking in 11 times the income of the nation's poorest 10 percent, the World Bank details. In the Slovak Republic, by income our globe's most equal nation, the top 10 percent only average triple the income of the poorest 10 percent.

The control over Colombia's land mass tells an even more top-heavy story. The nation's top 1 percent of private landholders own 81 percent of Colombia's acreage.

Taxes in Colombia do precious little to alter this striking maldistribution of income and wealth. The nation's personal income tax only kicks in at about four times Colombia's median income, a rate structure, the World Bank points out, that leaves most all of Colombia's rich paying no more than 10 percent of their actual total income in tax.

Colombia's social welfare programs, meanwhile, "suffer from large leakages to high-income households," and the nation's public pension system generates "subsides that accrue mostly to recipients of high pensions."

Dynamics like these have left Colombia's inequality the world's most entrenched. No nation scores worst on the "intergenerational persistence of earnings," a tag researchers use when they compare what parents earn to what their kids end up making. In a nation with persistently unequal earnings, parents who make over five times what average parents make will have children who make over five times average earnings.

Last fall's World Bank analysis of Colombia's deep-seated inequalities argues that reducing those inequalities makes eminent sense on both moral and economic grounds. Greater equality in Colombia, the World Bank analysts stress, would boost growth and promote social cohesion.

What these analysts don't stress: Greater equality in Colombia would also help save the Earth. The Amazon rainforest will never be safe as long as the key nations of the Amazon basin remain so unequal.

The increasingly concentrated ownership of Colombia's best agricultural land is driving poor farming families ever deeper into the rainforest.

Why does inequality in Colombia matter so much to our climate future? The increasingly concentrated ownership of Colombia's best agricultural land is driving poor farming families ever deeper into the rainforest. That same concentration has created a labor force desperate enough to take jobs with hustlers getting rich off of cattle-ranching, logging, and various other assaults on the rainforest.

Past presidents of Colombia could have, of course, addressed this desperation with programs to help the nation's most destitute. But paying for those programs would have required higher taxes on Colombia's most affluent, and, until this year, these affluents haven't had to face that particular prospect in quite some time.

In fact, the rich in Colombia haven't faced a national leader interested in seriously taxing them since Jorge Eliecer Gaitan Ayala--the last serious progressive candidate for Colombia's top office before Preto--died in a broad-daylight assassination during his 1948 presidential campaign.

Gustavo Petro and Francia Marquez will now be taking office after running on a platform that places the well-being of Colombia's poor and our global climate above the interests of the affluents who've dominated Colombia for so long. Their proposed agrarian reforms will guarantee rural families the right to land. Petro and Marquez have also pledged to phase out fossil fuels--including oil, Colombia's current top export--and protect their nation's incredibly rich biodiversity, one of the world's most expansive.

On taxes, the Petro government will be upping the ask on Colombia's "4,000 largest fortunes." Petro's initial prime targets include the dividend income that currently goes largely untaxed and wealth transfers abroad. Preto is promising, for instance, to deny government resources to individuals who maintain financial accounts in "tax haven" nations.

"Transfers abroad," notes Nick Corbishley, a British analyst who's traveled widely in South America, "make for an interesting target, given the propensity for wealthy Latin American businesses and families to move their money overseas, particularly to Miami, whenever a government of even mild left-wing persuasion comes into power."

Opposition from the affluent to Preto's environmental and equity agenda has, predictably, already begun to congeal.

"Petro's critics fear that his ambitious plans, including his redistributive policies and his proposal to ban new oil exploration, could ruin Colombia's economy," observes the Washington Post's Samantha Schmidt.

A good many Colombians, Schmidt reminds us, are already experiencing a ruined economy. Almost half of all Colombians are currently "experiencing some type of poverty and struggle to find enough to eat."

Yet Preto's critics, the Post analyst adds, can only see Preto's interest in declaring "an economic state of emergency to combat hunger" as evidence of "his willingness to work around democratic institutions to push through his agenda."

This sort of bogus "concern" for the rule of law has in the past regularly greased the skids for U.S. interventions that have helped topple left-leaning governments in Latin America that have refused to genuflect before their traditional national elites.

But those traditional elites have never faced the broad challenge they face now. If Lula takes the Brazilian presidency this fall, as polls indicate he will, progressives like Preto will be running Latin America's six largest nations.

The Amazon is cheering. We should be too.