SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

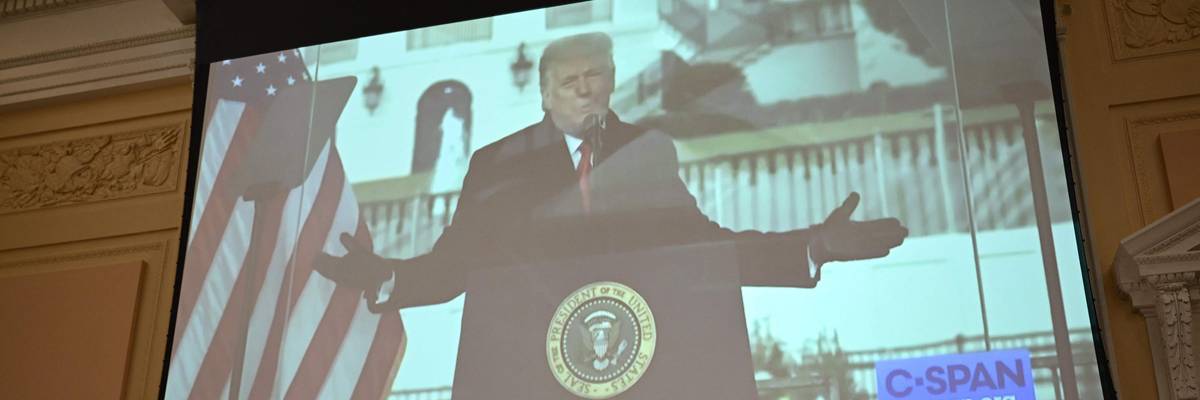

A screen shows former US President Donald Trump speaking on January 6, 2021 during a House Select Committee hearing to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the US Capitol, in the Cannon House Office Building on Capitol Hill in Washington, DC on June 9, 2022. (Photo by Brendan SMIALOWSKI / AFP) (Photo by BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

The House Jan. 6 committee hearings have raised two overarching questions. The first: Will the Justice Department indict and prosecute former President Donald Trump for leading a criminal conspiracy to steal the 2020 presidential election? The second: Will Congress enact essential reforms to protect our democracy from a future presidential coup attempt or insurrectionist attack on the U.S. Capitol?

The first question can ultimately be answered only by Attorney General Merrick Garland. Congress is now considering the second.

A bipartisan group of senators led by Sens. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., proposed two measures on Wednesday that would significantly reform flawed 19th-century laws that still govern U.S. presidential elections. Changes must be made to the Presidential Election Day Act of 1845 and the Electoral Count Act of 1887, into which the 1845 Act was incorporated.

The proposed bills open the door for the Senate to address the grave problems in these laws -- problems alarmingly dramatized by Trump's attempted presidential coup. It is increasingly clear that loopholes in the 1845 Act and problems in the Electoral Count Act were at the heart of Trump's effort to steal the 2020 election.

The Collins-Manchin proposal needs to be carefully vetted to ensure it will prevent future presidential coup attempts. It will also need 10 Republican senators to oppose a filibuster and no opposition from Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell to get through the Senate.

In addition, the Jan. 6 panel's vice chair, Rep. Lynn Cheney, R-Wy., and senior member Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif. issued a statement late Wednesday that the panel would be proposing its own bipartisan fix for repairing the Electoral Count Act.

Congress has the power, under Article 2, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution to determine when presidential electors are chosen. The 1845 Act sets the official quadrennial presidential Election Day on which voters chose the electors. It also provides that if a state "failed to make a choice" on Election Day, then the state's presidential electors may be chosen "in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct." There is no definition of what "failed to make a choice" requires.

This means a state legislature could simply decide that voters "failed to make a choice" based on allegations of widespread voter fraud -- or any other grounds the legislature chooses. It could then substitute its own choice of presidential electors for those voters chose on Election Day.

Sound far-fetched?

It was -- until Trump and coup strategist John Eastman tried to use that loophole to overturn Joe Biden's win.

We heard at the House Jan. 6 committee's June 23 session how the planning and plotting unfolded. Former acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen and former acting Deputy Attorney General Richard Donoghue testified about a letter that Jeffrey Clark, then acting head of the Justice Department's Civil Division, pressed them to sign.

The letter claimed -- falsely -- that the Justice Department had identified significant concerns about voting irregularities in multiple states, including Georgia. Once the letter was signed, Clark, working on behalf of Trump, planned to send it to Georgia's governor, House speaker and Senate president pro tempore -- all Republicans.

To solve this fabricated problem, the letter proposed that a special session of the Georgia Legislature be called. It would then "evaluate the irregularities" and "take whatever action is necessary" to ensure that the correct slate of electors is sent to Congress -- that is, the Trump slate, even though Biden won the state.

The letter cited the loophole in the 1845 Act as the basis for the Georgia Legislature to override voters and choose its own presidential electors.

Most critically, the letter cited the loophole in the 1845 Act as the basis for the Georgia Legislature to override voters and choose its own presidential electors. The letter said the act "explicitly recognizes the power that State Legislatures have to appoint electors" when voters "failed to make a choice" on Election Day.

Clark's proposed effort also involved the Justice Department sending similar letters to other battleground states with Republican-controlled legislatures.

Rosen and Donoghue flatly refused to sign the letter -- and a constitutional crisis was averted.

The blueprint, however, set forth a path for future coup plotters to follow. They would not even need the Justice Department. State legislatures could do it themselves -- and many in key battleground states are now controlled by Republicans.

The 1845 Act's "failure to choose" loophole is a ticking time bomb. Reform is essential to remove it and take away state legislatures' ability to override the voters' choice.

A second serious problem in the 19th-century laws was illustrated by Trump's January 2021 phone call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. Trump spent an hour pressuring the state official to change Georgia's presidential vote count. "All I want to do is this," Trump said in the call. "I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have because we won the state."

In other words, Trump tried to get Raffensperger to rig the vote. Raffensperger refused.

Trump's call certainly appears to violate both federal and Georgia state law. But this case shows how a rogue secretary of state or other empowered state official could certify the wrong presidential electors or refuse to certify any electors.

A presidential nominee adversely affected by such an action must be able to effectively challenge this in the courts. Precise reform provisions in the Electoral Count Act must be clearly spelled out to avoid any vagueness that could create ambiguities -- and thus create new opportunities to overturn a presidential election.

The reforms must provide a specific cause of action to challenge a wrongful certification or a failure to certify. They should also provide the right to expedited federal court review.

And the adversely affected presidential candidate must be provided with timely relief, because a new president is required to be certified on Jan. 6, only two months after Election Day. This does not leave much time for legal proceedings.

The plot to steal the 2020 presidential election was eye-opening. Congress must act now to ensure that any future attempt to steal the presidency does not succeed where this first one failed.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

The House Jan. 6 committee hearings have raised two overarching questions. The first: Will the Justice Department indict and prosecute former President Donald Trump for leading a criminal conspiracy to steal the 2020 presidential election? The second: Will Congress enact essential reforms to protect our democracy from a future presidential coup attempt or insurrectionist attack on the U.S. Capitol?

The first question can ultimately be answered only by Attorney General Merrick Garland. Congress is now considering the second.

A bipartisan group of senators led by Sens. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., proposed two measures on Wednesday that would significantly reform flawed 19th-century laws that still govern U.S. presidential elections. Changes must be made to the Presidential Election Day Act of 1845 and the Electoral Count Act of 1887, into which the 1845 Act was incorporated.

The proposed bills open the door for the Senate to address the grave problems in these laws -- problems alarmingly dramatized by Trump's attempted presidential coup. It is increasingly clear that loopholes in the 1845 Act and problems in the Electoral Count Act were at the heart of Trump's effort to steal the 2020 election.

The Collins-Manchin proposal needs to be carefully vetted to ensure it will prevent future presidential coup attempts. It will also need 10 Republican senators to oppose a filibuster and no opposition from Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell to get through the Senate.

In addition, the Jan. 6 panel's vice chair, Rep. Lynn Cheney, R-Wy., and senior member Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif. issued a statement late Wednesday that the panel would be proposing its own bipartisan fix for repairing the Electoral Count Act.

Congress has the power, under Article 2, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution to determine when presidential electors are chosen. The 1845 Act sets the official quadrennial presidential Election Day on which voters chose the electors. It also provides that if a state "failed to make a choice" on Election Day, then the state's presidential electors may be chosen "in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct." There is no definition of what "failed to make a choice" requires.

This means a state legislature could simply decide that voters "failed to make a choice" based on allegations of widespread voter fraud -- or any other grounds the legislature chooses. It could then substitute its own choice of presidential electors for those voters chose on Election Day.

Sound far-fetched?

It was -- until Trump and coup strategist John Eastman tried to use that loophole to overturn Joe Biden's win.

We heard at the House Jan. 6 committee's June 23 session how the planning and plotting unfolded. Former acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen and former acting Deputy Attorney General Richard Donoghue testified about a letter that Jeffrey Clark, then acting head of the Justice Department's Civil Division, pressed them to sign.

The letter claimed -- falsely -- that the Justice Department had identified significant concerns about voting irregularities in multiple states, including Georgia. Once the letter was signed, Clark, working on behalf of Trump, planned to send it to Georgia's governor, House speaker and Senate president pro tempore -- all Republicans.

To solve this fabricated problem, the letter proposed that a special session of the Georgia Legislature be called. It would then "evaluate the irregularities" and "take whatever action is necessary" to ensure that the correct slate of electors is sent to Congress -- that is, the Trump slate, even though Biden won the state.

The letter cited the loophole in the 1845 Act as the basis for the Georgia Legislature to override voters and choose its own presidential electors.

Most critically, the letter cited the loophole in the 1845 Act as the basis for the Georgia Legislature to override voters and choose its own presidential electors. The letter said the act "explicitly recognizes the power that State Legislatures have to appoint electors" when voters "failed to make a choice" on Election Day.

Clark's proposed effort also involved the Justice Department sending similar letters to other battleground states with Republican-controlled legislatures.

Rosen and Donoghue flatly refused to sign the letter -- and a constitutional crisis was averted.

The blueprint, however, set forth a path for future coup plotters to follow. They would not even need the Justice Department. State legislatures could do it themselves -- and many in key battleground states are now controlled by Republicans.

The 1845 Act's "failure to choose" loophole is a ticking time bomb. Reform is essential to remove it and take away state legislatures' ability to override the voters' choice.

A second serious problem in the 19th-century laws was illustrated by Trump's January 2021 phone call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. Trump spent an hour pressuring the state official to change Georgia's presidential vote count. "All I want to do is this," Trump said in the call. "I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have because we won the state."

In other words, Trump tried to get Raffensperger to rig the vote. Raffensperger refused.

Trump's call certainly appears to violate both federal and Georgia state law. But this case shows how a rogue secretary of state or other empowered state official could certify the wrong presidential electors or refuse to certify any electors.

A presidential nominee adversely affected by such an action must be able to effectively challenge this in the courts. Precise reform provisions in the Electoral Count Act must be clearly spelled out to avoid any vagueness that could create ambiguities -- and thus create new opportunities to overturn a presidential election.

The reforms must provide a specific cause of action to challenge a wrongful certification or a failure to certify. They should also provide the right to expedited federal court review.

And the adversely affected presidential candidate must be provided with timely relief, because a new president is required to be certified on Jan. 6, only two months after Election Day. This does not leave much time for legal proceedings.

The plot to steal the 2020 presidential election was eye-opening. Congress must act now to ensure that any future attempt to steal the presidency does not succeed where this first one failed.

The House Jan. 6 committee hearings have raised two overarching questions. The first: Will the Justice Department indict and prosecute former President Donald Trump for leading a criminal conspiracy to steal the 2020 presidential election? The second: Will Congress enact essential reforms to protect our democracy from a future presidential coup attempt or insurrectionist attack on the U.S. Capitol?

The first question can ultimately be answered only by Attorney General Merrick Garland. Congress is now considering the second.

A bipartisan group of senators led by Sens. Susan Collins, R-Maine, and Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., proposed two measures on Wednesday that would significantly reform flawed 19th-century laws that still govern U.S. presidential elections. Changes must be made to the Presidential Election Day Act of 1845 and the Electoral Count Act of 1887, into which the 1845 Act was incorporated.

The proposed bills open the door for the Senate to address the grave problems in these laws -- problems alarmingly dramatized by Trump's attempted presidential coup. It is increasingly clear that loopholes in the 1845 Act and problems in the Electoral Count Act were at the heart of Trump's effort to steal the 2020 election.

The Collins-Manchin proposal needs to be carefully vetted to ensure it will prevent future presidential coup attempts. It will also need 10 Republican senators to oppose a filibuster and no opposition from Senate Republican Leader Mitch McConnell to get through the Senate.

In addition, the Jan. 6 panel's vice chair, Rep. Lynn Cheney, R-Wy., and senior member Rep. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif. issued a statement late Wednesday that the panel would be proposing its own bipartisan fix for repairing the Electoral Count Act.

Congress has the power, under Article 2, Section 1, Clause 4 of the Constitution to determine when presidential electors are chosen. The 1845 Act sets the official quadrennial presidential Election Day on which voters chose the electors. It also provides that if a state "failed to make a choice" on Election Day, then the state's presidential electors may be chosen "in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct." There is no definition of what "failed to make a choice" requires.

This means a state legislature could simply decide that voters "failed to make a choice" based on allegations of widespread voter fraud -- or any other grounds the legislature chooses. It could then substitute its own choice of presidential electors for those voters chose on Election Day.

Sound far-fetched?

It was -- until Trump and coup strategist John Eastman tried to use that loophole to overturn Joe Biden's win.

We heard at the House Jan. 6 committee's June 23 session how the planning and plotting unfolded. Former acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen and former acting Deputy Attorney General Richard Donoghue testified about a letter that Jeffrey Clark, then acting head of the Justice Department's Civil Division, pressed them to sign.

The letter claimed -- falsely -- that the Justice Department had identified significant concerns about voting irregularities in multiple states, including Georgia. Once the letter was signed, Clark, working on behalf of Trump, planned to send it to Georgia's governor, House speaker and Senate president pro tempore -- all Republicans.

To solve this fabricated problem, the letter proposed that a special session of the Georgia Legislature be called. It would then "evaluate the irregularities" and "take whatever action is necessary" to ensure that the correct slate of electors is sent to Congress -- that is, the Trump slate, even though Biden won the state.

The letter cited the loophole in the 1845 Act as the basis for the Georgia Legislature to override voters and choose its own presidential electors.

Most critically, the letter cited the loophole in the 1845 Act as the basis for the Georgia Legislature to override voters and choose its own presidential electors. The letter said the act "explicitly recognizes the power that State Legislatures have to appoint electors" when voters "failed to make a choice" on Election Day.

Clark's proposed effort also involved the Justice Department sending similar letters to other battleground states with Republican-controlled legislatures.

Rosen and Donoghue flatly refused to sign the letter -- and a constitutional crisis was averted.

The blueprint, however, set forth a path for future coup plotters to follow. They would not even need the Justice Department. State legislatures could do it themselves -- and many in key battleground states are now controlled by Republicans.

The 1845 Act's "failure to choose" loophole is a ticking time bomb. Reform is essential to remove it and take away state legislatures' ability to override the voters' choice.

A second serious problem in the 19th-century laws was illustrated by Trump's January 2021 phone call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. Trump spent an hour pressuring the state official to change Georgia's presidential vote count. "All I want to do is this," Trump said in the call. "I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have because we won the state."

In other words, Trump tried to get Raffensperger to rig the vote. Raffensperger refused.

Trump's call certainly appears to violate both federal and Georgia state law. But this case shows how a rogue secretary of state or other empowered state official could certify the wrong presidential electors or refuse to certify any electors.

A presidential nominee adversely affected by such an action must be able to effectively challenge this in the courts. Precise reform provisions in the Electoral Count Act must be clearly spelled out to avoid any vagueness that could create ambiguities -- and thus create new opportunities to overturn a presidential election.

The reforms must provide a specific cause of action to challenge a wrongful certification or a failure to certify. They should also provide the right to expedited federal court review.

And the adversely affected presidential candidate must be provided with timely relief, because a new president is required to be certified on Jan. 6, only two months after Election Day. This does not leave much time for legal proceedings.

The plot to steal the 2020 presidential election was eye-opening. Congress must act now to ensure that any future attempt to steal the presidency does not succeed where this first one failed.