SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

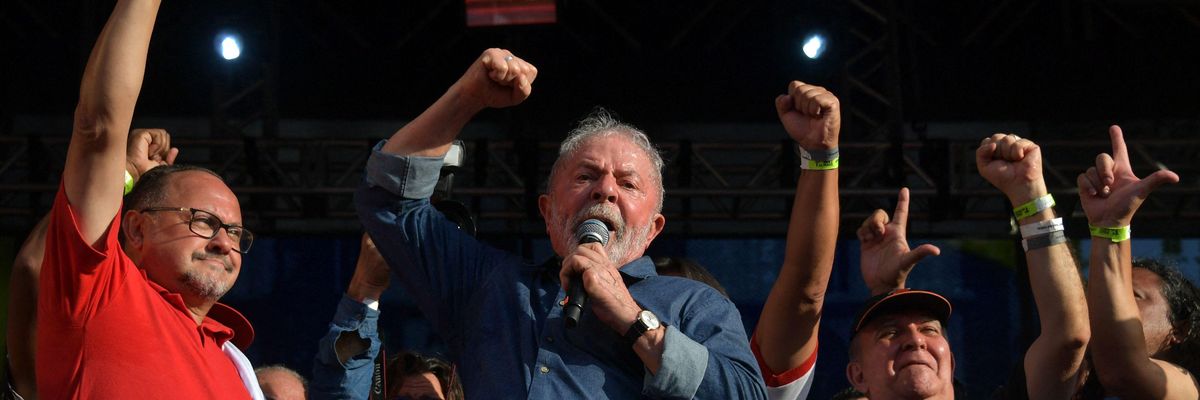

Former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva delivers a speech during a May Day (Labour Day) rally to mark the international day of the workers, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, on May 1, 2022. (Photo: Nelson Almeida/AFP via Getty Images)

In less than a month, Brazilian voters will elect their next president. One might imagine that the unpopular far-right incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, doesn't stand a chance. But Bolsonaro retains the support of some very powerful forces, and he continues to pose a severe threat to Brazilian democracy.

The international community must be ready to act if Bolsonaro or Brazil's military attempt to subvert the election's results.

Since coming to power in 2019, Bolsonaro has seemingly made it his mission to dismantle Brazil's democratic institutions. Almost immediately upon taking office, he stripped Brazil's federal agency for indigenous affairs, FUNAI, of key powers. He subsequently appointed Marcelo Xavier da Silva--a police officer linked to agribusiness--to head the agency, opening the way for the removal of protections of indigenous lands. Likewise, Brazil's main environmental agency, Ibama, has suffered from budget cuts, political interference, and the weakening of regulations. And Bolsonaro--a former army captain--has encouraged the politicization of the armed forces and the regional military police.

If Bolsonaro secures another term in office, these trends will only worsen. After all, elected autocrats tend to escalate their efforts to destroy democracy after their second electoral victory. So, how likely is another Bolsonaro term?

In one recent poll, 59% of respondents said they would never vote for Bolsonaro, and 61% disapproved of his governance. Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who served as president from 2003 to 2010 and was released from prison in 2019 after serving less than two years of a 12-year sentence for passive corruption (which was annulled last year, after the convicting judge's impartiality was impugned), is far more likely to win.

But Bolsonaro's approval rating has recently improved slightly. Moreover, a large segment of Brazil's political class--the so-called "Centrao," which comprises center-right and right-wing parties--has stuck by Bolsonaro, in exchange for ministerial jobs and funding from a highly opaque "secret budget." Notably, Bolsonaro has effectively handed over control of the public budget to House Speaker Arthur Lira, a Bolsonaro ally who has become Brazil's de facto prime minister.

Far from fulfilling his campaign promise to fight corruption and to reform Brazilian politics, Bolsonaro has revived the parties and figures most exposed to the corruption scandals of the last two decades and profoundly degraded Brazilian democracy. And much of the political class has supported him in the process.

Not surprisingly, Bolsonaro has also tried to buy public support, even though Brazilian law prohibits campaign handouts. Amid rising inflation, he has increased monthly stipends to 18 million poor Brazilian families (until December 2022), offered cash to taxi drivers and small farmers, provided transportation subsidies to the elderly, and more. He is also pushing tax cuts, including on fuel.

Even if this is not enough to ensure his re-election in October, Bolsonaro has been showing all the signs of a leader who could well engineer a constitutional coup. Already, he has questioned the integrity of Brazilian institutions and invoked the possibility of electoral fraud. The electronic voting system that Brazil has used successfully for more than 25 years is now apparently "vulnerable to manipulation."

In this sense, Bolsonaro seems to be taking a page out of former US President Donald Trump's playbook. While the January 2021 attack on the US Capitol that Trump incited did not keep him in power, it did not make him or the Republican Party a pariah, either. And whereas the US military was highly unlikely to step in to back a Trump-led coup, the Brazilian military seems more concerned with controlling elections than safeguarding the country. Last year, the defense ministry sent more than 80 questions about the electoral process to Brazil's supreme electoral court (TSE), the body that oversees elections. Then, it announced that it would organize a parallel "inspection plan" for the election, including its own vote count.

Moreover, citizens, activists, and candidates are facing physical threats. Following the murder in June of English journalist Dom Phillips and anthropologist Bruno Pereira in the Amazon, a Workers' Party activist was shot by a Bolsonaro supporter. In this environment of growing political violence, Lula has resolved to wear a bulletproof vest during his public meetings.

Even if Bolsonaro loses by a large margin in October, Brazilian democracy will face a tough stress test. But a Bolsonaro victory--or even a narrow loss--would bode far worse for Brazil. That is why it is so important for democratic forces in Brazil to put aside their differences and form a united front against Bolsonaro and his extremist supporters.

Lula is already working to build this broad front. His most audacious political gesture so far was to invite Geraldo Alckmin--a former governor of Sao Paulo, former leader of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), and Lula's rival in the 2006 presidential election--to be his running mate. But Lula must go even further, inviting all leaders who share his desire to restore democratic normalcy to work together to isolate Bolsonaro and his backers in Congress, the judiciary, and other influential positions. And any candidate with even a remote chance of winning the election--namely, Ciro Gomes and Simone Tebet--should endorse Lula's campaign, in order to help prevent a Bolsonaro victory.

For its part, the international community must be ready to act if Bolsonaro or Brazil's military attempt to subvert the election's results. After all, Brazil's descent into authoritarianism has implications that extend far beyond the country's borders, not least because of the Amazon's critical importance to the future of the planet.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

In less than a month, Brazilian voters will elect their next president. One might imagine that the unpopular far-right incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, doesn't stand a chance. But Bolsonaro retains the support of some very powerful forces, and he continues to pose a severe threat to Brazilian democracy.

The international community must be ready to act if Bolsonaro or Brazil's military attempt to subvert the election's results.

Since coming to power in 2019, Bolsonaro has seemingly made it his mission to dismantle Brazil's democratic institutions. Almost immediately upon taking office, he stripped Brazil's federal agency for indigenous affairs, FUNAI, of key powers. He subsequently appointed Marcelo Xavier da Silva--a police officer linked to agribusiness--to head the agency, opening the way for the removal of protections of indigenous lands. Likewise, Brazil's main environmental agency, Ibama, has suffered from budget cuts, political interference, and the weakening of regulations. And Bolsonaro--a former army captain--has encouraged the politicization of the armed forces and the regional military police.

If Bolsonaro secures another term in office, these trends will only worsen. After all, elected autocrats tend to escalate their efforts to destroy democracy after their second electoral victory. So, how likely is another Bolsonaro term?

In one recent poll, 59% of respondents said they would never vote for Bolsonaro, and 61% disapproved of his governance. Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who served as president from 2003 to 2010 and was released from prison in 2019 after serving less than two years of a 12-year sentence for passive corruption (which was annulled last year, after the convicting judge's impartiality was impugned), is far more likely to win.

But Bolsonaro's approval rating has recently improved slightly. Moreover, a large segment of Brazil's political class--the so-called "Centrao," which comprises center-right and right-wing parties--has stuck by Bolsonaro, in exchange for ministerial jobs and funding from a highly opaque "secret budget." Notably, Bolsonaro has effectively handed over control of the public budget to House Speaker Arthur Lira, a Bolsonaro ally who has become Brazil's de facto prime minister.

Far from fulfilling his campaign promise to fight corruption and to reform Brazilian politics, Bolsonaro has revived the parties and figures most exposed to the corruption scandals of the last two decades and profoundly degraded Brazilian democracy. And much of the political class has supported him in the process.

Not surprisingly, Bolsonaro has also tried to buy public support, even though Brazilian law prohibits campaign handouts. Amid rising inflation, he has increased monthly stipends to 18 million poor Brazilian families (until December 2022), offered cash to taxi drivers and small farmers, provided transportation subsidies to the elderly, and more. He is also pushing tax cuts, including on fuel.

Even if this is not enough to ensure his re-election in October, Bolsonaro has been showing all the signs of a leader who could well engineer a constitutional coup. Already, he has questioned the integrity of Brazilian institutions and invoked the possibility of electoral fraud. The electronic voting system that Brazil has used successfully for more than 25 years is now apparently "vulnerable to manipulation."

In this sense, Bolsonaro seems to be taking a page out of former US President Donald Trump's playbook. While the January 2021 attack on the US Capitol that Trump incited did not keep him in power, it did not make him or the Republican Party a pariah, either. And whereas the US military was highly unlikely to step in to back a Trump-led coup, the Brazilian military seems more concerned with controlling elections than safeguarding the country. Last year, the defense ministry sent more than 80 questions about the electoral process to Brazil's supreme electoral court (TSE), the body that oversees elections. Then, it announced that it would organize a parallel "inspection plan" for the election, including its own vote count.

Moreover, citizens, activists, and candidates are facing physical threats. Following the murder in June of English journalist Dom Phillips and anthropologist Bruno Pereira in the Amazon, a Workers' Party activist was shot by a Bolsonaro supporter. In this environment of growing political violence, Lula has resolved to wear a bulletproof vest during his public meetings.

Even if Bolsonaro loses by a large margin in October, Brazilian democracy will face a tough stress test. But a Bolsonaro victory--or even a narrow loss--would bode far worse for Brazil. That is why it is so important for democratic forces in Brazil to put aside their differences and form a united front against Bolsonaro and his extremist supporters.

Lula is already working to build this broad front. His most audacious political gesture so far was to invite Geraldo Alckmin--a former governor of Sao Paulo, former leader of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), and Lula's rival in the 2006 presidential election--to be his running mate. But Lula must go even further, inviting all leaders who share his desire to restore democratic normalcy to work together to isolate Bolsonaro and his backers in Congress, the judiciary, and other influential positions. And any candidate with even a remote chance of winning the election--namely, Ciro Gomes and Simone Tebet--should endorse Lula's campaign, in order to help prevent a Bolsonaro victory.

For its part, the international community must be ready to act if Bolsonaro or Brazil's military attempt to subvert the election's results. After all, Brazil's descent into authoritarianism has implications that extend far beyond the country's borders, not least because of the Amazon's critical importance to the future of the planet.

In less than a month, Brazilian voters will elect their next president. One might imagine that the unpopular far-right incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, doesn't stand a chance. But Bolsonaro retains the support of some very powerful forces, and he continues to pose a severe threat to Brazilian democracy.

The international community must be ready to act if Bolsonaro or Brazil's military attempt to subvert the election's results.

Since coming to power in 2019, Bolsonaro has seemingly made it his mission to dismantle Brazil's democratic institutions. Almost immediately upon taking office, he stripped Brazil's federal agency for indigenous affairs, FUNAI, of key powers. He subsequently appointed Marcelo Xavier da Silva--a police officer linked to agribusiness--to head the agency, opening the way for the removal of protections of indigenous lands. Likewise, Brazil's main environmental agency, Ibama, has suffered from budget cuts, political interference, and the weakening of regulations. And Bolsonaro--a former army captain--has encouraged the politicization of the armed forces and the regional military police.

If Bolsonaro secures another term in office, these trends will only worsen. After all, elected autocrats tend to escalate their efforts to destroy democracy after their second electoral victory. So, how likely is another Bolsonaro term?

In one recent poll, 59% of respondents said they would never vote for Bolsonaro, and 61% disapproved of his governance. Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who served as president from 2003 to 2010 and was released from prison in 2019 after serving less than two years of a 12-year sentence for passive corruption (which was annulled last year, after the convicting judge's impartiality was impugned), is far more likely to win.

But Bolsonaro's approval rating has recently improved slightly. Moreover, a large segment of Brazil's political class--the so-called "Centrao," which comprises center-right and right-wing parties--has stuck by Bolsonaro, in exchange for ministerial jobs and funding from a highly opaque "secret budget." Notably, Bolsonaro has effectively handed over control of the public budget to House Speaker Arthur Lira, a Bolsonaro ally who has become Brazil's de facto prime minister.

Far from fulfilling his campaign promise to fight corruption and to reform Brazilian politics, Bolsonaro has revived the parties and figures most exposed to the corruption scandals of the last two decades and profoundly degraded Brazilian democracy. And much of the political class has supported him in the process.

Not surprisingly, Bolsonaro has also tried to buy public support, even though Brazilian law prohibits campaign handouts. Amid rising inflation, he has increased monthly stipends to 18 million poor Brazilian families (until December 2022), offered cash to taxi drivers and small farmers, provided transportation subsidies to the elderly, and more. He is also pushing tax cuts, including on fuel.

Even if this is not enough to ensure his re-election in October, Bolsonaro has been showing all the signs of a leader who could well engineer a constitutional coup. Already, he has questioned the integrity of Brazilian institutions and invoked the possibility of electoral fraud. The electronic voting system that Brazil has used successfully for more than 25 years is now apparently "vulnerable to manipulation."

In this sense, Bolsonaro seems to be taking a page out of former US President Donald Trump's playbook. While the January 2021 attack on the US Capitol that Trump incited did not keep him in power, it did not make him or the Republican Party a pariah, either. And whereas the US military was highly unlikely to step in to back a Trump-led coup, the Brazilian military seems more concerned with controlling elections than safeguarding the country. Last year, the defense ministry sent more than 80 questions about the electoral process to Brazil's supreme electoral court (TSE), the body that oversees elections. Then, it announced that it would organize a parallel "inspection plan" for the election, including its own vote count.

Moreover, citizens, activists, and candidates are facing physical threats. Following the murder in June of English journalist Dom Phillips and anthropologist Bruno Pereira in the Amazon, a Workers' Party activist was shot by a Bolsonaro supporter. In this environment of growing political violence, Lula has resolved to wear a bulletproof vest during his public meetings.

Even if Bolsonaro loses by a large margin in October, Brazilian democracy will face a tough stress test. But a Bolsonaro victory--or even a narrow loss--would bode far worse for Brazil. That is why it is so important for democratic forces in Brazil to put aside their differences and form a united front against Bolsonaro and his extremist supporters.

Lula is already working to build this broad front. His most audacious political gesture so far was to invite Geraldo Alckmin--a former governor of Sao Paulo, former leader of the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), and Lula's rival in the 2006 presidential election--to be his running mate. But Lula must go even further, inviting all leaders who share his desire to restore democratic normalcy to work together to isolate Bolsonaro and his backers in Congress, the judiciary, and other influential positions. And any candidate with even a remote chance of winning the election--namely, Ciro Gomes and Simone Tebet--should endorse Lula's campaign, in order to help prevent a Bolsonaro victory.

For its part, the international community must be ready to act if Bolsonaro or Brazil's military attempt to subvert the election's results. After all, Brazil's descent into authoritarianism has implications that extend far beyond the country's borders, not least because of the Amazon's critical importance to the future of the planet.