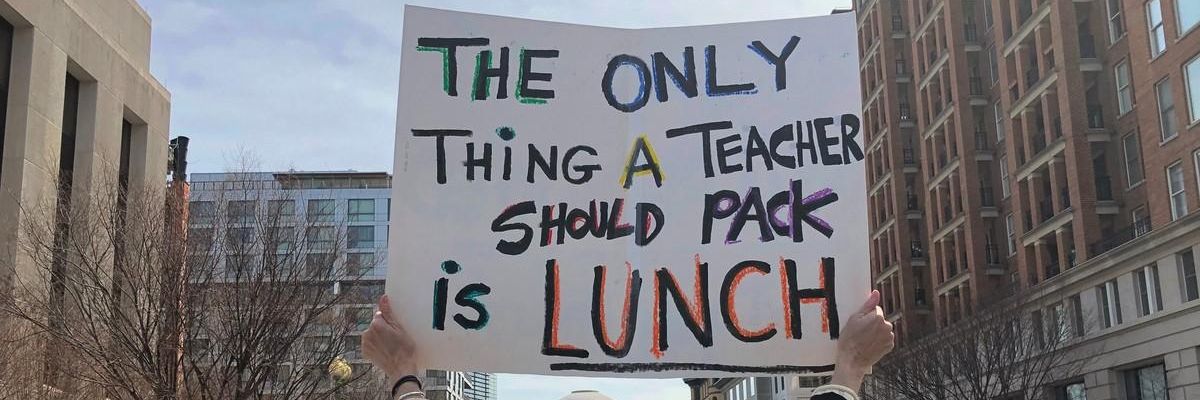

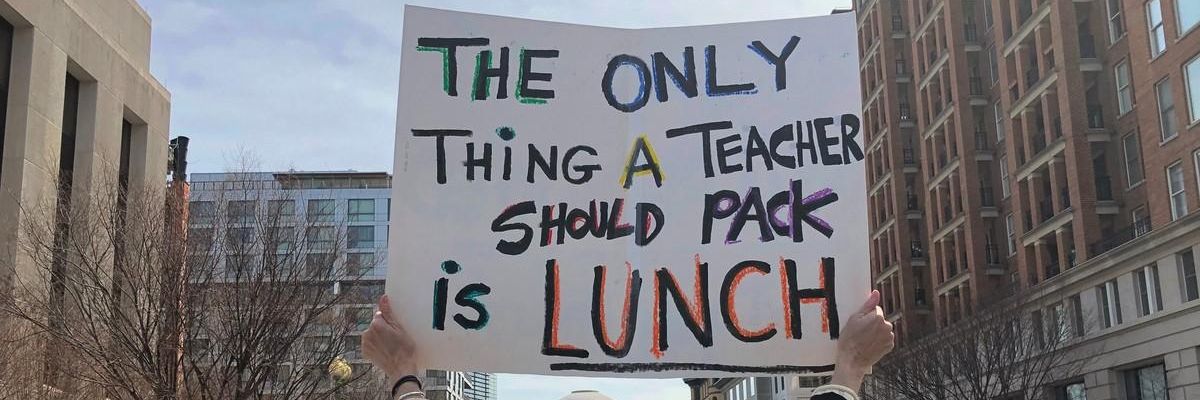

Teachers, students, and parents rally for gun control in Washington, D.C. on March 24, 2018. (Photo: Giles Clarke/Getty Images)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Teachers, students, and parents rally for gun control in Washington, D.C. on March 24, 2018. (Photo: Giles Clarke/Getty Images)

I will never forget the afternoon before my very first day as a middle school teacher in central New Jersey. Textbooks and worksheets sat strewn across my bed in the house I shared with my father. I was 25 years old and had just received my teaching license. My nerves were frayed--as every novice teacher knows, there is absolutely nothing more terrifying than a new classroom full of young people.

This interpretation of a teacher's job responsibilities is nothing more than a way to pass the buck and burden educators with a problem that only our legislators can solve.

On that day before school began, I had been obsessing over classroom procedures, introductory activities, and the first week's lessons that I hoped would be engaging. I did not sleep much the night before and survived my first week of teaching on pure adrenaline. I wondered whether my students would like me and whether they would want to be in my classroom. I was desperate to earn their families' trust and looked forward to the opportunity to forge relationships over the following year.

I was not preoccupied with escape routes, closets and cabinets in which to hide from bullets, or fears that a gunman might make his way into the school and down the hall to my English Language Arts classroom.

This was 16 years ago. My formal teacher preparation did not include workshops and simulations that dealt with the possibility of my demise the way teachers and students are now required to, with highly choreographed active attacker drills.

While we certainly had lockdown procedures, at that time they felt like a formality rather than a necessity. In 2006--the year I began my teaching career--there were 11 school shootings, and they all seemed to occur worlds away from my New Jersey classroom. There have so far been 29 school shootings this year, and 118 since 2018, according to Education Week, which tracks school climate and safety.

I think most educators are now bonded by the same fear: It is no longer a question of if a school is rocked by shooting, but when. That leaves me with a burning, seething rage at a small but powerful group of politicians for allowing this travesty to continue unabated.

I now teach students at the college level. My job is centred on preparing future teachers to take charge of their own classrooms, an experience that culminates in state licensure. This process requires that they develop expertise in content, current theories and methods for effective teaching. Our simulations involve classroom read-alouds, Socratic questioning techniques and debates and discussions about themes in novels.

They do not involve teaching future teachers how to disarm and overtake a school attacker. That should not be the job of teachers. Politicians--not teachers--are the ones who should be losing sleep as they figure out how to solve this crisis. This is why we vote for them; this is why we pay their salaries with our tax dollars.

But congressmen such as Texas Senator Ted Cruz and former President Donald Trump want to arm teachers in their classrooms as the answer to the gun violence epidemic. This interpretation of a teacher's job responsibilities is nothing more than a way to pass the buck and burden educators with a problem that only our legislators can solve.

Yet our politicians continue to bury their heads in the sand. For instance, Michigan Republicans have blocked all efforts to institute reasonable gun control measures in the wake of the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, Texas, in May.

This move was a stinging slap in the face, considering that Michigan was the site of another recent mass shooting last December when a high school student murdered four of his peers at Oxford High School.

This move was a stinging slap in the face, considering that Michigan was the site of another recent mass shooting last December when a high school student murdered four of his peers at Oxford High School.

Texas teachers have protested loudly against Ted Cruz's response to the Uvalde school shooting, even marching to his office in Austin. Our priorities are clear: Teachers want safe classrooms where they can focus on the work of teaching and learning. Only in the United States is this considered a tall order.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

I will never forget the afternoon before my very first day as a middle school teacher in central New Jersey. Textbooks and worksheets sat strewn across my bed in the house I shared with my father. I was 25 years old and had just received my teaching license. My nerves were frayed--as every novice teacher knows, there is absolutely nothing more terrifying than a new classroom full of young people.

This interpretation of a teacher's job responsibilities is nothing more than a way to pass the buck and burden educators with a problem that only our legislators can solve.

On that day before school began, I had been obsessing over classroom procedures, introductory activities, and the first week's lessons that I hoped would be engaging. I did not sleep much the night before and survived my first week of teaching on pure adrenaline. I wondered whether my students would like me and whether they would want to be in my classroom. I was desperate to earn their families' trust and looked forward to the opportunity to forge relationships over the following year.

I was not preoccupied with escape routes, closets and cabinets in which to hide from bullets, or fears that a gunman might make his way into the school and down the hall to my English Language Arts classroom.

This was 16 years ago. My formal teacher preparation did not include workshops and simulations that dealt with the possibility of my demise the way teachers and students are now required to, with highly choreographed active attacker drills.

While we certainly had lockdown procedures, at that time they felt like a formality rather than a necessity. In 2006--the year I began my teaching career--there were 11 school shootings, and they all seemed to occur worlds away from my New Jersey classroom. There have so far been 29 school shootings this year, and 118 since 2018, according to Education Week, which tracks school climate and safety.

I think most educators are now bonded by the same fear: It is no longer a question of if a school is rocked by shooting, but when. That leaves me with a burning, seething rage at a small but powerful group of politicians for allowing this travesty to continue unabated.

I now teach students at the college level. My job is centred on preparing future teachers to take charge of their own classrooms, an experience that culminates in state licensure. This process requires that they develop expertise in content, current theories and methods for effective teaching. Our simulations involve classroom read-alouds, Socratic questioning techniques and debates and discussions about themes in novels.

They do not involve teaching future teachers how to disarm and overtake a school attacker. That should not be the job of teachers. Politicians--not teachers--are the ones who should be losing sleep as they figure out how to solve this crisis. This is why we vote for them; this is why we pay their salaries with our tax dollars.

But congressmen such as Texas Senator Ted Cruz and former President Donald Trump want to arm teachers in their classrooms as the answer to the gun violence epidemic. This interpretation of a teacher's job responsibilities is nothing more than a way to pass the buck and burden educators with a problem that only our legislators can solve.

Yet our politicians continue to bury their heads in the sand. For instance, Michigan Republicans have blocked all efforts to institute reasonable gun control measures in the wake of the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, Texas, in May.

This move was a stinging slap in the face, considering that Michigan was the site of another recent mass shooting last December when a high school student murdered four of his peers at Oxford High School.

This move was a stinging slap in the face, considering that Michigan was the site of another recent mass shooting last December when a high school student murdered four of his peers at Oxford High School.

Texas teachers have protested loudly against Ted Cruz's response to the Uvalde school shooting, even marching to his office in Austin. Our priorities are clear: Teachers want safe classrooms where they can focus on the work of teaching and learning. Only in the United States is this considered a tall order.

I will never forget the afternoon before my very first day as a middle school teacher in central New Jersey. Textbooks and worksheets sat strewn across my bed in the house I shared with my father. I was 25 years old and had just received my teaching license. My nerves were frayed--as every novice teacher knows, there is absolutely nothing more terrifying than a new classroom full of young people.

This interpretation of a teacher's job responsibilities is nothing more than a way to pass the buck and burden educators with a problem that only our legislators can solve.

On that day before school began, I had been obsessing over classroom procedures, introductory activities, and the first week's lessons that I hoped would be engaging. I did not sleep much the night before and survived my first week of teaching on pure adrenaline. I wondered whether my students would like me and whether they would want to be in my classroom. I was desperate to earn their families' trust and looked forward to the opportunity to forge relationships over the following year.

I was not preoccupied with escape routes, closets and cabinets in which to hide from bullets, or fears that a gunman might make his way into the school and down the hall to my English Language Arts classroom.

This was 16 years ago. My formal teacher preparation did not include workshops and simulations that dealt with the possibility of my demise the way teachers and students are now required to, with highly choreographed active attacker drills.

While we certainly had lockdown procedures, at that time they felt like a formality rather than a necessity. In 2006--the year I began my teaching career--there were 11 school shootings, and they all seemed to occur worlds away from my New Jersey classroom. There have so far been 29 school shootings this year, and 118 since 2018, according to Education Week, which tracks school climate and safety.

I think most educators are now bonded by the same fear: It is no longer a question of if a school is rocked by shooting, but when. That leaves me with a burning, seething rage at a small but powerful group of politicians for allowing this travesty to continue unabated.

I now teach students at the college level. My job is centred on preparing future teachers to take charge of their own classrooms, an experience that culminates in state licensure. This process requires that they develop expertise in content, current theories and methods for effective teaching. Our simulations involve classroom read-alouds, Socratic questioning techniques and debates and discussions about themes in novels.

They do not involve teaching future teachers how to disarm and overtake a school attacker. That should not be the job of teachers. Politicians--not teachers--are the ones who should be losing sleep as they figure out how to solve this crisis. This is why we vote for them; this is why we pay their salaries with our tax dollars.

But congressmen such as Texas Senator Ted Cruz and former President Donald Trump want to arm teachers in their classrooms as the answer to the gun violence epidemic. This interpretation of a teacher's job responsibilities is nothing more than a way to pass the buck and burden educators with a problem that only our legislators can solve.

Yet our politicians continue to bury their heads in the sand. For instance, Michigan Republicans have blocked all efforts to institute reasonable gun control measures in the wake of the Robb Elementary School shooting in Uvalde, Texas, in May.

This move was a stinging slap in the face, considering that Michigan was the site of another recent mass shooting last December when a high school student murdered four of his peers at Oxford High School.

This move was a stinging slap in the face, considering that Michigan was the site of another recent mass shooting last December when a high school student murdered four of his peers at Oxford High School.

Texas teachers have protested loudly against Ted Cruz's response to the Uvalde school shooting, even marching to his office in Austin. Our priorities are clear: Teachers want safe classrooms where they can focus on the work of teaching and learning. Only in the United States is this considered a tall order.