SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

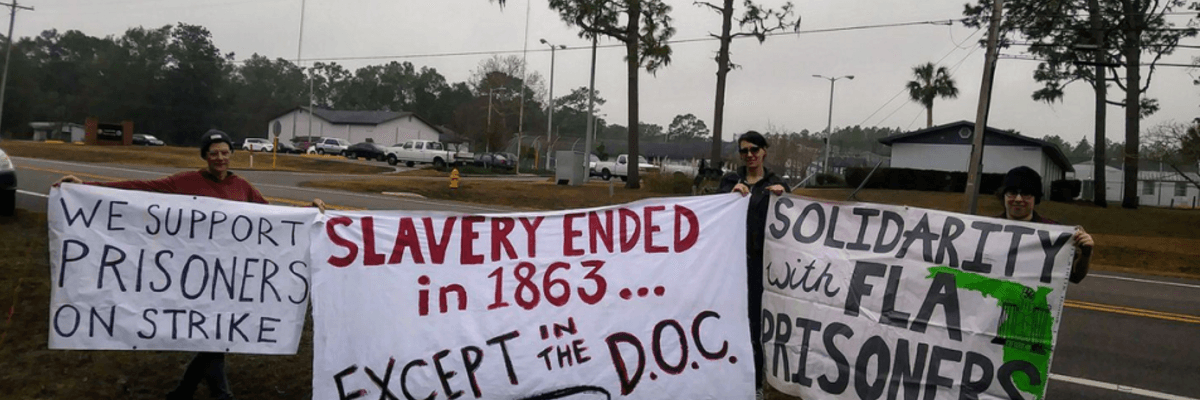

Our nation fought a battle to end slavery because it is obviously wrong, and it's still obviously wrong in prison. (Photo: Screenshot)

Constitution Week commemorates the landmark document that underpins our nation's government and celebrates the rights afforded to us as citizens. But for me and many others, the day is a cruel reminder that there are hundreds of thousands of people behind bars who are excluded from key rights afforded by the US Constitution, including the protection from slavery or involuntary servitude. To the surprise of many, slavery is still permitted by the 13th Amendment when used as criminal punishment.

It's time we send a message to corporations that we will not stand for their exploitation of the most insidious loophole written into our Constitution.

Due to this exception, I was enslaved in prison--forced to work long, hard hours for little pay while others profited handsomely.

For seven years, I was paid pennies an hour for my work in a metal fabrication plant in Stillwater, a Minnesota prison. Alongside over a hundred other incarcerated men, I built large shipping containers used to ship industrial-sized rolls of paper for 3M, a global office supply conglomerate that owns brands like Post-it and Scotch.

It was back-breaking work. We had quotas. If we missed them, we were disciplined.

Despite the intensity of our skilled labor, the starting pay was 50 cents an hour. Every 90 days, we got a small raise, a few more pennies, but most people maxed out at a dollar an hour. For every ten people who worked in the plant, only two could earn as much as $1.50 an hour and just one person was allowed to make it to $2.25 an hour.

Outside of prison, people can generally choose the type of work they do, the hours they work, and the wages they'll work for. Of course not everyone gets their dream job, but employment laws help guarantee wages and other important employment protections. In prison, we have neither choices nor protections.

At Stillwater, if you didn't apply for a job, they issued you a job. If you quit that job, you were disciplined. If you didn't have a job, you weren't allowed to go to recreation with the general population and you lost basic privileges. In fact, you could only come out of your cell for about an hour and a half a day. So, you either worked or you suffered the consequences: punishment on top of punishment.

Unsurprisingly, everyone applied for a job. People would compete over the better paying jobs, those that paid 50 rather than 25 cents an hour. They weren't good jobs and they certainly weren't jobs that prepared us for post-release careers, but they were better than the alternative. The lesser of evils, you might say. We made do with what we had while those we worked for reaped the real benefits.

After my release, I learned that an estimated $14 billion in wages are stolen every year from incarcerated workers across the country. This devastating reality is made possible by an exception written into the Thirteenth Amendment of U.S. the Constitution, which prohibits slavery except as punishment for crime.

When I look back on my time at Stillwater with what I know now, the words of the exception clause in the Thirteenth Amendment contradict the promise of emancipation. Our nation fought a battle to end slavery because it is obviously wrong, and it's still obviously wrong in prison.

Thankfully there are campaigns igniting across the country to abolish slavery, for all, including those in prison. States like Colorado, Utah, and Nebraska recently amended their state constitutions to remove any exception to the abolition of slavery, and many others are going to the ballot this November do the same. And last year, Senator Jeff Merkley (OR) and Congresswoman Nikema Williams (GA-05) introduced the Abolition Amendment in Congress to end the exception in the Thirteenth Amendment.

While these critical fights continue, one thing that we can all do immediately is to stop supporting brands like 3M that use prison slavery and contribute to the expansion of mass incarceration with our hard earned dollars. It's time we send a message to corporations that we will not stand for their exploitation of the most insidious loophole written into our Constitution. Together, we can truly abolish slavery in our country without exception, so that next year we're celebrating the Constitutional rights of all.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Constitution Week commemorates the landmark document that underpins our nation's government and celebrates the rights afforded to us as citizens. But for me and many others, the day is a cruel reminder that there are hundreds of thousands of people behind bars who are excluded from key rights afforded by the US Constitution, including the protection from slavery or involuntary servitude. To the surprise of many, slavery is still permitted by the 13th Amendment when used as criminal punishment.

It's time we send a message to corporations that we will not stand for their exploitation of the most insidious loophole written into our Constitution.

Due to this exception, I was enslaved in prison--forced to work long, hard hours for little pay while others profited handsomely.

For seven years, I was paid pennies an hour for my work in a metal fabrication plant in Stillwater, a Minnesota prison. Alongside over a hundred other incarcerated men, I built large shipping containers used to ship industrial-sized rolls of paper for 3M, a global office supply conglomerate that owns brands like Post-it and Scotch.

It was back-breaking work. We had quotas. If we missed them, we were disciplined.

Despite the intensity of our skilled labor, the starting pay was 50 cents an hour. Every 90 days, we got a small raise, a few more pennies, but most people maxed out at a dollar an hour. For every ten people who worked in the plant, only two could earn as much as $1.50 an hour and just one person was allowed to make it to $2.25 an hour.

Outside of prison, people can generally choose the type of work they do, the hours they work, and the wages they'll work for. Of course not everyone gets their dream job, but employment laws help guarantee wages and other important employment protections. In prison, we have neither choices nor protections.

At Stillwater, if you didn't apply for a job, they issued you a job. If you quit that job, you were disciplined. If you didn't have a job, you weren't allowed to go to recreation with the general population and you lost basic privileges. In fact, you could only come out of your cell for about an hour and a half a day. So, you either worked or you suffered the consequences: punishment on top of punishment.

Unsurprisingly, everyone applied for a job. People would compete over the better paying jobs, those that paid 50 rather than 25 cents an hour. They weren't good jobs and they certainly weren't jobs that prepared us for post-release careers, but they were better than the alternative. The lesser of evils, you might say. We made do with what we had while those we worked for reaped the real benefits.

After my release, I learned that an estimated $14 billion in wages are stolen every year from incarcerated workers across the country. This devastating reality is made possible by an exception written into the Thirteenth Amendment of U.S. the Constitution, which prohibits slavery except as punishment for crime.

When I look back on my time at Stillwater with what I know now, the words of the exception clause in the Thirteenth Amendment contradict the promise of emancipation. Our nation fought a battle to end slavery because it is obviously wrong, and it's still obviously wrong in prison.

Thankfully there are campaigns igniting across the country to abolish slavery, for all, including those in prison. States like Colorado, Utah, and Nebraska recently amended their state constitutions to remove any exception to the abolition of slavery, and many others are going to the ballot this November do the same. And last year, Senator Jeff Merkley (OR) and Congresswoman Nikema Williams (GA-05) introduced the Abolition Amendment in Congress to end the exception in the Thirteenth Amendment.

While these critical fights continue, one thing that we can all do immediately is to stop supporting brands like 3M that use prison slavery and contribute to the expansion of mass incarceration with our hard earned dollars. It's time we send a message to corporations that we will not stand for their exploitation of the most insidious loophole written into our Constitution. Together, we can truly abolish slavery in our country without exception, so that next year we're celebrating the Constitutional rights of all.

Constitution Week commemorates the landmark document that underpins our nation's government and celebrates the rights afforded to us as citizens. But for me and many others, the day is a cruel reminder that there are hundreds of thousands of people behind bars who are excluded from key rights afforded by the US Constitution, including the protection from slavery or involuntary servitude. To the surprise of many, slavery is still permitted by the 13th Amendment when used as criminal punishment.

It's time we send a message to corporations that we will not stand for their exploitation of the most insidious loophole written into our Constitution.

Due to this exception, I was enslaved in prison--forced to work long, hard hours for little pay while others profited handsomely.

For seven years, I was paid pennies an hour for my work in a metal fabrication plant in Stillwater, a Minnesota prison. Alongside over a hundred other incarcerated men, I built large shipping containers used to ship industrial-sized rolls of paper for 3M, a global office supply conglomerate that owns brands like Post-it and Scotch.

It was back-breaking work. We had quotas. If we missed them, we were disciplined.

Despite the intensity of our skilled labor, the starting pay was 50 cents an hour. Every 90 days, we got a small raise, a few more pennies, but most people maxed out at a dollar an hour. For every ten people who worked in the plant, only two could earn as much as $1.50 an hour and just one person was allowed to make it to $2.25 an hour.

Outside of prison, people can generally choose the type of work they do, the hours they work, and the wages they'll work for. Of course not everyone gets their dream job, but employment laws help guarantee wages and other important employment protections. In prison, we have neither choices nor protections.

At Stillwater, if you didn't apply for a job, they issued you a job. If you quit that job, you were disciplined. If you didn't have a job, you weren't allowed to go to recreation with the general population and you lost basic privileges. In fact, you could only come out of your cell for about an hour and a half a day. So, you either worked or you suffered the consequences: punishment on top of punishment.

Unsurprisingly, everyone applied for a job. People would compete over the better paying jobs, those that paid 50 rather than 25 cents an hour. They weren't good jobs and they certainly weren't jobs that prepared us for post-release careers, but they were better than the alternative. The lesser of evils, you might say. We made do with what we had while those we worked for reaped the real benefits.

After my release, I learned that an estimated $14 billion in wages are stolen every year from incarcerated workers across the country. This devastating reality is made possible by an exception written into the Thirteenth Amendment of U.S. the Constitution, which prohibits slavery except as punishment for crime.

When I look back on my time at Stillwater with what I know now, the words of the exception clause in the Thirteenth Amendment contradict the promise of emancipation. Our nation fought a battle to end slavery because it is obviously wrong, and it's still obviously wrong in prison.

Thankfully there are campaigns igniting across the country to abolish slavery, for all, including those in prison. States like Colorado, Utah, and Nebraska recently amended their state constitutions to remove any exception to the abolition of slavery, and many others are going to the ballot this November do the same. And last year, Senator Jeff Merkley (OR) and Congresswoman Nikema Williams (GA-05) introduced the Abolition Amendment in Congress to end the exception in the Thirteenth Amendment.

While these critical fights continue, one thing that we can all do immediately is to stop supporting brands like 3M that use prison slavery and contribute to the expansion of mass incarceration with our hard earned dollars. It's time we send a message to corporations that we will not stand for their exploitation of the most insidious loophole written into our Constitution. Together, we can truly abolish slavery in our country without exception, so that next year we're celebrating the Constitutional rights of all.