When the world's nations convene in Durban in November in the latest attempt to inch towards a global deal to tackle climate change, one fundamental principle will, as ever, underlie the negotiations.

Is is the contention that while rich, industrialised nations caused climate change through past carbon emissions, it is the developing world that is bearing the brunt. It follows from that, developing nations say, that the rich nations must therefore pay to enable the developing nations to both develop cleanly and adapt to the impacts of global warming.

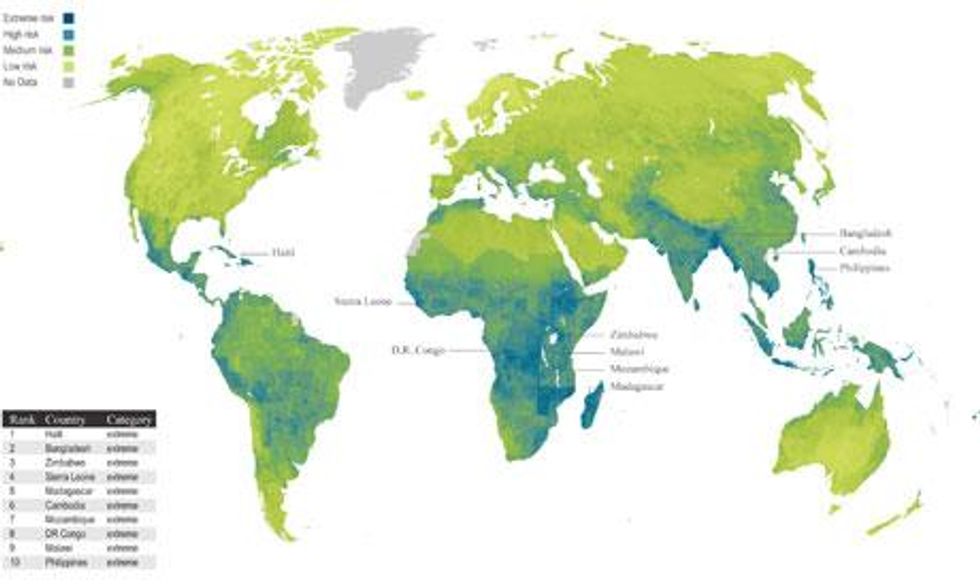

The point is starkly illustrated in a new map of climate vulnerability (above): the rich global north has low vulnerability, the poor global south has high vulnerability. The map is produced by risk analysts Maplecroft by combining measures of the risk of climate change impacts, such as storms, floods, and droughts, with the social and financial ability of both communities and governments to cope. The top three most vulnerable nations reflect all these factors: Haiti, Bangladesh, Zimbabwe.

But it is not until you go all the way down 103 on the list, out of 193 nations, that you encounter the first major developed nation: Greece. The first 102 nations are all developing ones. Italy is next, at 124, and like Greece ranks relatively highly due to the risk of drought. The UK is at 178 and the country on Earth least vulnerable to climate change, according to Maplecroft, is Iceland.

"Large areas of north America and northern Europe are not so exposed to actual climate risk, and are very well placed to deal with it," explains Charlie Beldon, principal analyst at Maplecroft.

The vulnerability index has been calculated down to a resolution of 25km2 and Beldon says at this scale the vulnerability of the developing world's fast growing cities becomes clear. "A lot of big cities have developed in exposed areas such as flood plains, such as in south east Asia, and in developing economies they so don't have the capacity to adapt."

Of the world's 20 fastest growing cities, six are classified as 'extreme risk' by Maplecroft, including Calcutta in India, Manila in the Philippines, Jakarta in Indonesia and Dhaka and Chittagong in Bangladesh. Addis Ababa in Ethiopia also features. A further 10 are rated as 'high risk' including Guangdong, Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai, Karachi and Lagos.

"Cities such as Manila, Jakarta and Calcutta are vital centres of economic growth in key emerging markets, but heat waves, flooding, water shortages and increasingly severe and frequent storm events may well increase as climate changes takes hold," says Beldon.

With the world on the verge of a population of seven billion people, the rapid urbanisation of many developing countries remains one of the major demographic trends, but piles on risk because of the higher pressure on resources, such as water, and city infrastructure, like roads and hospitals.

Helen Hodge, head of maps and indices at Maplecroft, says it is not only local populations at risk from climate change impacts, serious though that is. The breaking of international supply chains for businesses working in a globalised world is also a big risk, she says.

"The recent flooding in Bangkok shows how very large multinationals can have long supply chains put at risk," she says, noting that Thailand is the world's largest producer of hard-disk computer drives.

China, the world's workshop, sits almost exactly halfway in the vulnerability index at 98 out of 193. That's appropriate, as China now sits awkwardly between the nations getting rich on carbon emissions and those suffering from its effects. And that's the other major contention that will underpin the UN climate talks in Durban.