SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

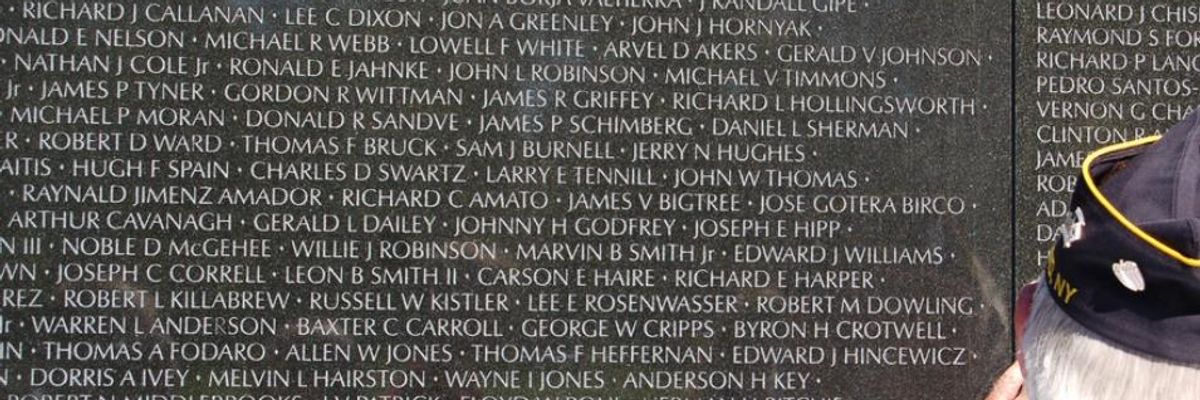

The Vietnam Veterans Memorial. (Photo: Jonathan & Jill)

Four decades after the Vietnam War, roughly 283,000 veterans are still plagued by post-traumatic stress disorder, with few showing any progress towards recovery, according to a study released last week by the American Psychological Association. The average veteran included in the study was 67 years old.

PTSD is characterized by vivid flashbacks, sleep problems, and hyper-arousal. Individuals suffering from the disorder often report that the symptoms interfere with their daily lives, leading to depression, anxiety, and social isolation, among other side effects. The study, which updated information from the early 1980s that brought the disorder to public attention more than 20 years ago, also found that a large percentage of veterans with combat stress commit suicide, particularly if they had preexisting trauma before enlisting. Soldiers who reported abuse as children were three to eight times more likely to have suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Dr. Charles Marmar, an author of both the original study and the follow-up, told the New York Times that a drastic change will be necessary to provide the necessary mental health care to help service members with the disorder. "A significant number of veterans are going to have PTSD for a lifetime unless we do something radically different," said Marmar, who is also chairman of psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center and director of the NYU Cohen Veterans Center.

While the total percentage of Vietnam veterans with PTSD has diminished somewhat, the numbers are not promising -- they've decreased from 15 to 11 percent since the 80s. Many have died from physical problems linked to the disorders, such as heart disease and cancer. Researchers tracked down almost 80 percent of the 2,348 people who participated in the first study, but more than 500 had died. Approximately 18 percent had died by the time they reached retirement age -- twice as many as those who did not have the disorder. Black and Hispanic veterans were also two to three times more likely to develop it.

According to government figures, about 120,000 veterans sought treatment for the condition in 2012 alone. More than 60 percent of soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have been diagnosed with PTSD or other traumatic brain injuries since returning home.

Marmar, who authored the report with Dr. William Schlenger of Massachusetts-based research firm Abt Associates, said the new analysis is part of the first effort to track a large sample of soldiers and other service members throughout their lives, and will likely have implications for future PTSD treatment and programs.

"The study's key takeaway is that for some, PTSD is not going away. It is chronic and prolonged. And for veterans with PTSD, the war is not over," Schlenger told USA Today.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Four decades after the Vietnam War, roughly 283,000 veterans are still plagued by post-traumatic stress disorder, with few showing any progress towards recovery, according to a study released last week by the American Psychological Association. The average veteran included in the study was 67 years old.

PTSD is characterized by vivid flashbacks, sleep problems, and hyper-arousal. Individuals suffering from the disorder often report that the symptoms interfere with their daily lives, leading to depression, anxiety, and social isolation, among other side effects. The study, which updated information from the early 1980s that brought the disorder to public attention more than 20 years ago, also found that a large percentage of veterans with combat stress commit suicide, particularly if they had preexisting trauma before enlisting. Soldiers who reported abuse as children were three to eight times more likely to have suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Dr. Charles Marmar, an author of both the original study and the follow-up, told the New York Times that a drastic change will be necessary to provide the necessary mental health care to help service members with the disorder. "A significant number of veterans are going to have PTSD for a lifetime unless we do something radically different," said Marmar, who is also chairman of psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center and director of the NYU Cohen Veterans Center.

While the total percentage of Vietnam veterans with PTSD has diminished somewhat, the numbers are not promising -- they've decreased from 15 to 11 percent since the 80s. Many have died from physical problems linked to the disorders, such as heart disease and cancer. Researchers tracked down almost 80 percent of the 2,348 people who participated in the first study, but more than 500 had died. Approximately 18 percent had died by the time they reached retirement age -- twice as many as those who did not have the disorder. Black and Hispanic veterans were also two to three times more likely to develop it.

According to government figures, about 120,000 veterans sought treatment for the condition in 2012 alone. More than 60 percent of soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have been diagnosed with PTSD or other traumatic brain injuries since returning home.

Marmar, who authored the report with Dr. William Schlenger of Massachusetts-based research firm Abt Associates, said the new analysis is part of the first effort to track a large sample of soldiers and other service members throughout their lives, and will likely have implications for future PTSD treatment and programs.

"The study's key takeaway is that for some, PTSD is not going away. It is chronic and prolonged. And for veterans with PTSD, the war is not over," Schlenger told USA Today.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Four decades after the Vietnam War, roughly 283,000 veterans are still plagued by post-traumatic stress disorder, with few showing any progress towards recovery, according to a study released last week by the American Psychological Association. The average veteran included in the study was 67 years old.

PTSD is characterized by vivid flashbacks, sleep problems, and hyper-arousal. Individuals suffering from the disorder often report that the symptoms interfere with their daily lives, leading to depression, anxiety, and social isolation, among other side effects. The study, which updated information from the early 1980s that brought the disorder to public attention more than 20 years ago, also found that a large percentage of veterans with combat stress commit suicide, particularly if they had preexisting trauma before enlisting. Soldiers who reported abuse as children were three to eight times more likely to have suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Dr. Charles Marmar, an author of both the original study and the follow-up, told the New York Times that a drastic change will be necessary to provide the necessary mental health care to help service members with the disorder. "A significant number of veterans are going to have PTSD for a lifetime unless we do something radically different," said Marmar, who is also chairman of psychiatry at NYU Langone Medical Center and director of the NYU Cohen Veterans Center.

While the total percentage of Vietnam veterans with PTSD has diminished somewhat, the numbers are not promising -- they've decreased from 15 to 11 percent since the 80s. Many have died from physical problems linked to the disorders, such as heart disease and cancer. Researchers tracked down almost 80 percent of the 2,348 people who participated in the first study, but more than 500 had died. Approximately 18 percent had died by the time they reached retirement age -- twice as many as those who did not have the disorder. Black and Hispanic veterans were also two to three times more likely to develop it.

According to government figures, about 120,000 veterans sought treatment for the condition in 2012 alone. More than 60 percent of soldiers who served in Iraq and Afghanistan have been diagnosed with PTSD or other traumatic brain injuries since returning home.

Marmar, who authored the report with Dr. William Schlenger of Massachusetts-based research firm Abt Associates, said the new analysis is part of the first effort to track a large sample of soldiers and other service members throughout their lives, and will likely have implications for future PTSD treatment and programs.

"The study's key takeaway is that for some, PTSD is not going away. It is chronic and prolonged. And for veterans with PTSD, the war is not over," Schlenger told USA Today.

The study was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs.