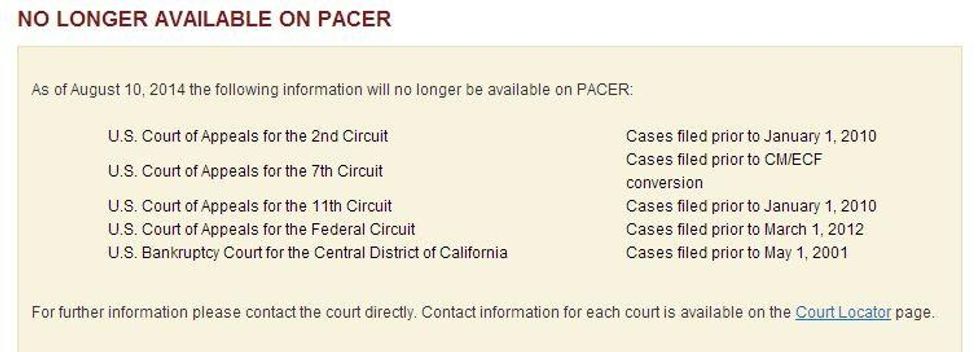

A decade of records from four U.S. appeals courts and one bankruptcy court were lost earlier this month when the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) quietly deleted a massive amount of data that was "incompatible" with an impending upgrade.

"As of August 10, the following information will no longer be available on PACER," read a statement on the company's website, which was published after the files were wiped on August 11. The statement was re-written a few days later to say, "[T]he judiciary is no longer able to provide electronic access to the closed cases on those systems. The dockets and documents in these cases can be obtained directly from the relevant court."

The relevant courts in question are in New York City, Washington, D.C., Chicago, Atlanta, and Los Angeles. The Administrative Office defended the decision by noting that the cases that were removed were closed and that many had not been accessed in several years. Karen Redmond, a spokesperson for the Administrative Office, told Common Dreams, "Some of these cases have been closed for over 13 years. Anything that's open remains available at the courts."

But Brian Carver, co-founder of Free Law Project and an assistant professor at University of California at Berkeley School of Information, said many of the files were "very relevant and very recent" and others were landmark civil rights cases. "If these five courts don't provide some kind of accommodation... it will be extremely problematic for practitioners, for researchers, for the public who just want to find out about a big case," Carver told Common Dreams. "PACER is so difficult and so expensive that its usage statistics should tell us nothing about the importance of these files."

Lawyers, researchers, or any member of the public would have to physically visit the courthouses to see the dockets. The AO does not have a plan to provide access to the documents for those who cannot travel to the courthouses at any given time, Redmond said. However, it seems that some individual courts have made efforts to respond to individual requests -- in the case of the Second Circuit, which lost all files entered before January 2010, the clerk's office is willing to email documents for a $30 fee per case.

PACER also charges 10 cents per search and per page downloaded. Critics of the system have pointed to the government raising PACER's fees without making it easier to navigate. California Watch writes:

[L]awmakers on the House Appropriations Committee have allowed the courts to invest in a wider range of informationtechnology projects using fees collected from PACER...

"Given the lack of oversight for what the fees are being used for, the incentive for the courts is to raise fees," said Stephen Schultze, associate director of Princeton University's Center for Information Technology Policy.

In response to the dump, several lawyers and nonprofit organizations sent letters to Chief Judges of the courts to ask for access to the documents. Among them were Free Law Project and Public.Resource.Org, which told the judges that they wanted to conduct privacy research and add the files to a separate online archive that they would manage to "provide public access to historians, lawyers, journalists, and others."

"We would like to provide public access to these important court records which have permanent historical value," wrote Carl Malamud, head of Public.Resource.Org.

Free Law Project partners with Princeton's Center for Information Technology Policy to operate the RECAP platform, a crowd-sourced project which hosts free archives of court files that have been obtained through PACER.

"What appears on PACER dockets is far more than just the court decision," Carver told Common Dreams. "It's that secondary material that's irreplaceable."

Redmond said she did not know whether the AO had a plan to restore the files. "I'm not ruling it out, but it would require some time and personnel to do... which we're a little short of," she told Common Dreams.