'A Feeling It's Gonna Be Huge': Naomi Klein on People's Climate Eve

'The real task for progressive movements,' says author and activist, 'is to convince people that change is possible.'

On the eve of the People's Climate March in New York City and parallel People's Climate Mobilization actions happening in thousands of locations across the planet on Sunday, author and activist Naomi Klein spoke with Common Dreams about the unique and profound historical moment that the crisis of climate change now presents for humanity.

Framed around some of the ideas presented in her new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, Klein talks about why she's optimistic for the future despite the unprecedented challenges that have for too long been ignored by world leaders, industrial elites, and even many of the world's hard-hitting economic and social justice advocates.

"Love will save this place..."

"I think there's this really powerful click going on for a lot of people who've been engaged in economic justice issues for a long time," Klein told Common Dreams. And now, she says, there's an enormous and growing number of people "really ready to jump into the climate fight with both feet" because "they know it's not somebody's else issue."

And the march in New York--now expected to draw well over 100,000 (and possibly twice that) to the streets of Manhattan --Klein argues is vital not because it will achieve anything in an immediate "linear" sense, but because it will powerfully help destroy the "cognitive dissonance of living in a culture where people are absorbing this terrifying news about the destabilization of our [planet]" on the one hand while on the other being surrounded "by messages from popular culture and political leaders who are acting as though nothing is happening."

People all over the world, says Klein, are showing that they now know nothing less than radical solutions will suffice and what these people, organizations, and communities will be saying collectively on Sunday is simple: "We see this as an emergency and we want to act."

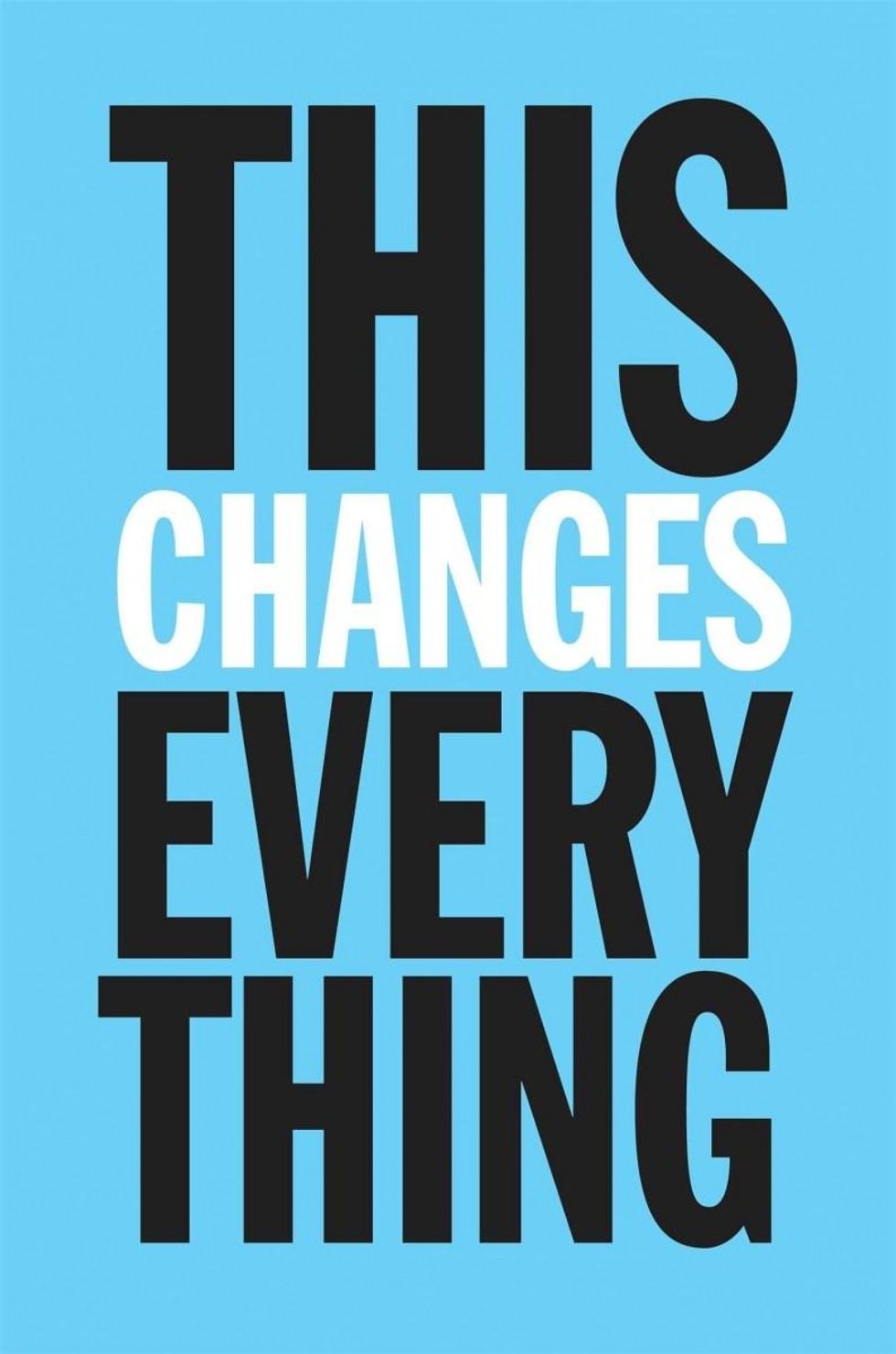

Common Dreams: The cover of the new book makes a statement. First of all, it does not have two hands holding the earth or letters spelled out in leafy greens or flames of red. In fact, the letters are black and blue. We don't judge books by covers, of course, but any significance to those choices?

Naomi Klein: Well, there were other cover designs proposed. It was of those things where I knew what I didn't want, but I didn't know what I wanted. And then Scott Richardson, the artistic director at Random House Canada, designed this cover and as soon as I saw it I said, 'Yeah, that one.'

In terms of the black and blue --I don't know what you're implying (laughter)--but I love the optimism of the color and I just think it's a smart design because if climate change 'changes everything' then it should push everything else off the cover, including the subtitle and my name. It was interesting because it wasn't a no-brainer for the publisher, particularly for my American publisher, to go with such a risky cover design. But I'm really glad they decided to go with that. I think it was a brave move. It may backfire terribly -- as they pile up in remainder bins -- but that remains to be seen. I think that people like that it looks like a poster--or I least that's what I like about it.

What about the title? Was it clear to you that this was it early on in the project--or did it come at some specific moment along the way?

This project was actually really hard to name, in fact. It went through a few different names. With [my first book] No Logo I had that title right away, from before I even wrote it, whereas this book has gone through several titles. One way to say it is, I guess, is that I knew what I wanted the title to express, before I knew how to express it. The moment itself?... I was just walking home from yoga one day and it came to me.

"What I really think works about the title is that it starts the conversation where the conversation needs to start. "But, of course, its a name that's out there. But I think it's the combination of the subject and the name that's working. And what I really think works about the title is that it starts the conversation where the conversation needs to start.

The title starts the conversation with the idea that there are no non-radical solutions available to us -- that we've left the crisis unaddressed for too long -- so that now we're looking at radical physical change, radical engineering change, or radical economic/political change. And I think when that is put to people they kind of know that. And so that's what I like about it, is that starts the conversation in a good place.

You've said that the urgency of the climate crisis means that we have to break every rule in the free-market playbook. Are there also rules in the Left's playbook that have to be broken?

Yes. There are.

It's why I have a chapter in the book about extractivism as a worldview that is the hallmark of the post-industrial age and is common to both the left and the right, or has been traditionally. And that most of the big battles are not over whether we're going to have an extractivist relationship with the planet, acting as if resources are infinite or as if we don't need to think about the long-term consequences of our depletion of resources and our pollution. Instead, the battles are over really over the distribution of the spoils.

"So people who haven't read the book say, Is she saying that communism is good for the environment? And the answer is: I'm not."Certainly there is a Marxist critique of the ecological contradiction, but in terms of the real world application of those ideas--the way in which they were applied by centralized, industrial socialist states (or states that called themselves socialist)--those states were on the whole just as polluting, but also explicitly at war with nature. Quite literally, as we know, Mao had a "war against nature." And I say in the book that in the Soviet era emissions in the Eastern Bloc states were comparable or even higher than countries like Canada and Australia.

So people who haven't read the book say, "Is she saying that communism is good for the environment?" And the answer is: I'm not. And that's why I"m talking about a shift in worldview. And its a shift in worldview that is beginning and where you see it most starkly is in the conflicts between some of the left governments that have come to power in Latin America and the Indigenous-led movements that helped bring them to power. In [Bolivian President Evo] Morales' second term he's increasingly in conflict with that base over precisely this issue of an extractivist-based policy. And it's complicated because Morales is using the proceeds from his extractivist policies to fight poverty in a very real way. But there are also very real costs to those policies. And, of course, Venezuela is a pretty classic example.

But these conflicts are coming to a head in Brazil over dams; very strong conflicts in Ecuador over oil drilling in the Amazon -- so I think that this question, Does this require the Left to break some of its rules?, the answer is yes, because -- particularly in the United States, the Left is still very much in a Keynesian model, pursuing growth-based policies, it's just that they want to distribute the growth better.

You talk in separate sections of the book about two fetishes that strike you as troubling. One is the "fetish of centrism" that we see in elite policy circles and the "fetish of structurelessness" that exists elsewhere. Could you explain what you mean by both and how they play into the urgency of the climate crisis?

It's interesting because generally on the Left you have that sense of urgency, but that the idea that engaging with the state is so compromised that you can't do it is a barrier to winning political victories that can move us forward at the speed that we need to move forward. But I do see some signs of change on that front.

"I see now that this urgency -- both in the sense of austerity and the crisis of inequality and the ecological crisis -- is driving this generation of activists to get their hands dirty."I see, for instance, the Indignados movement in Spain having an offshoot political party, Podemos, which has a really visionary policy. And in Montreal, Canada, there's a political party there, called Solidaire, and its economic policies are incredibly strong and has environmental policies that directly connect acting on climate and opposing the tar sands and pipelines and opposing the austerity agenda. They have a really strong platform and they have three MPs and strong ties to social movements. And in the U.S., you have an occupy activist becoming a city councilor in Seattle and helping to win the victories for higher minimum wage.

And the example I write about in the book about Germany is a really interesting one in this context. Germany's green transition -- now being held up by pretty much everybody as one of the most staggering green transitions anywhere in the world, where in after a decade and a half they have 25 percent of their electricity coming from renewables and much of it decentralized--that was the result of a movement victory. That was the result of the fact that Germany has a very strong environmental movement, a very strong anti-nuclear movement, but it was a movement that has engaged with policy. And whether they're running for office is not the issue. They are helping to design policy and they are trying to defend that policy now against attempts to erode some of those victories for decentralization and efforts to bring in more big players. And that has something to do with the interplay between social movements, the Left parties, and Parliament -- but I don't think that the "fetish for structurelessness" and this kind of opting out of engaging with policy it was for my generation -- you know, for the Seattle generation. I see now that this urgency -- both in the sense of austerity and the crisis of inequality and the ecological crisis -- is driving this generation of activists to get their hands dirty. Which is good, I think. They're doing it better than we did.

And what about that connection between that anti-globalization movement that rose during the 1990's and the current climate justice movement that many of the same organizations and activists, yourself included, are now engaged so deeply with?

Well, the truth is, I don't think of them as separate issues or different movements. And in the book I talk about the connection between that globalization process that enabled multinationals to search the world for the cheapest possible labor was also simultaneously searching the world for the cheapest energy. Of course, it was. So of course the success of that model has coincided with an emissions explosion. And I think that it's maybe taken us a while to draw these very obvious connections and I think that part of that has to do with our own failures to just get in there on climate.

"I think that it's maybe taken us a while to draw these very obvious connections and I think that part of that has to do with our own failures to just get in there on climate."I think there was this sense, and I've said this before, that for many this was the one issue that you didn't have to deal with because it seem like all these very well-funded, green NGOs were taking care of it. And many people had a lot on their plate so in some ways it was kind of outsourced -- and that was a really bad idea. But I think part of it was also just this weird way in which the whole climate discourse pretended that globalization wasn't happening in that key period in which we were suppose to be fighting climate change.

For instance, in the accounting system that was established by the UN to stipulate which countries are responsible for which emissions, no country is accountable for the emissions associations with transportation of goods across borders. So all of those freighter ships filled with goods, crossing the oceans, nobody is responsible for those emissions. And that's amazing. Or the fact that we have a system in which countries are responsible for the emissions associated with the goods that we consume, but not the emissions that go into producing or transporting those goods to us, across borders. So the television in your living room, that was made in China, you are accountable for the emissions that go in to turning it on and watching it, but none of the emissions that went into making it are transporting it. The emissions that went into making it are on China's bill and the emissions that went into transporting across the ocean went onto no one's bill.

This all represents, I think, this weird myopia and unwillingness to engage with some of these blatant contradictions between what was going on in the climate negotiations and what was going on simultaneously in the trade negotiations. And now, we see that they were clearly in conflict, because emissions are going up associated with that so-called free-trade explosion and that whole model, but also because many of the things we need to do to get off fossil fuels are being ruled illegal by the World Trade Organization and under agreements like NAFTA.

What are 'Beautiful Solutions'?

Well, I call this a project not a book because while I've been writing the book, my husband Avi Lewis -- who has worked in television for many years for the CBC and Al Jazeera and we also made a documentary together called The Take -- has been making a documentary film on the same topic. So it's not an adaptation of the book, because we've working on this in parallel -- but as I've been writing the book, he's been making this film. And there are points of intersection where we've documented the same thing. For instance, we went to Montana and I documented the fight against coal mining and some of the people doing incredible work, but you'll also meet them in the movie. And this makes me really happy, because maybe in the book there might be one or two quotes from them but in the film they're actual real people and you go to their house, you get to know them and they're amazing. So I think that's really great.

So Avi's going to be coming out with this film in January and we put way more thought into this project than we've been able to in the past. We both see our work as being tools for movements. We believe that the culture we produce should be part of the project of social change--that's what we want anyway. But we've always done this in a pretty ad hoc way. I've always just kind of gotten lucky, you know. No Logo came out just as the Seattle protests were happening and I just got swept up in that wave. And with The Take we had this great experience of the film being screened inside occupied factories and could see it being used as a tool for workers considering forming co-ops and things like that.

"We want to use these moments, to the extent that we can, to open up spaces for the movements that we are working with--and that our work would be impossible without--to speak for themselves."But with this project on climate change we wanted to do it in a more deliberate way. And so we've had something akin to outreach or an engagement strategy from the beginning -- from the earliest days -- where we've been having meetings with the social movements that I'm writing about and that Avi has been filming. And we've talked about how the cultural moments that sometimes come along with the writing of a book or the making of a film can be of more help to movements.

This weekend, for instance, ahead of the People's Climate March in New York we're hosting a summit with a bunch of the climate groups that are in town and one of the things we're going to be talking about -- once the film is done -- is having a series of teach-ins that can be useful to these organizations' members. So part of this project is that we've launched this website and we've partnered with a great editorial team that previously put together a book called "Beautiful Trouble," which looks at resistance strategies. And the next logical step for them was a project called "Beautiful Solutions" where they're documenting the real-world solutions that are emerging, particularly in frontline communities. That book isn't published yet, but they are pre-publishing a bunch of their stuff on the website. So they aren't us and we're aren't them, but we've partnered for this project and we're really excited about both the partnership and the work.

There can be a weird thing that happens when a book gets published -- you know, I've been lucky with my books and I get a certain amount of media attention -- so we want to use these moments, to the extent that we can, to open up spaces for the movements that we are working with--and that our work would be impossible without--to speak for themselves. That's why a few nights ago, at my book launch in New York, you know, I spoke for twenty minutes (not forty-five minutes) and then we had a great panel discussion with some of the terrific climate justice activists from the labor movement and the Indigenous rights movement and people like Esperanza Martinez--who I quote in my book --from Accion Ecologica in Ecuador. This is kind of the model that we're trying to figure out.

So you've had a week now (perhaps more) to talk in depth about your book... and now you're in New York on the eve of the People's Climate March & Mobilization (billed as the "largest climate mobilization in the history of the world") and the Flood Wall Street event in the financial district on Monday. How are you feeling? What are seeing? What's been most striking so far?

I just feel there's this really powerful "click" going on for a lot of people who've been engaged in economic justice issues for a long time. They are now really ready to jump into the climate fight with both feet and they know it's not somebody's else issue. And a lot of friends of mine who for a long time who kind of said, "Oh, that's your thing" or "I know you're doing this climate thing now, but I'll see you afterwards." -- those people are now saying, "Yeah. Of course, I'm going."

"We must find ways to show that we're not so far gone, that we're not so hopeless, that we're not so corrupted, that we're not so greedy and that we still could act to save ourselves."We're talking before the march, but I've got a feeling it's gonna be huge. And I know there's a been a debate about 'Who's marching?' or whether it means anything, but I just think the experience of just seeing how many people feel passionately about this issue is going to be so important to break that sense of isolation and just the cognitive dissonance of living in a culture where you are absorbing this terrifying news about the destabilization of our home, on the one hand, and to be surrounding by messages from popular culture and our political leaders who are acting as though nothing is happening. So I think there's something really important about moments of coming together to say, 'No. We see this as an emergency and we want to act."

So I don't think it's about whether this march is going to accomplish something linear, but I do think that it's going to nourish this movement in a really important way.

And what I have found most striking as I've been talking to journalists for the last couple of weeks is that I was so prepared to have people challenge me about how radical the conclusions are or how radical the changes have to be. Or maybe disagree with me science isn't that alarming. My amazing researchers and I spent a lot of time anticipating those kinds of attacks. But what's actually happened is that I've spent most of my time talking to journalists who want to argue with me about whether there's any hope at all. So they're agreeing with the conclusions about the need for radical change, and what they disagree with is the idea that there's any hope at all.

So I think it's a pretty extraordinary political moment. And where so many people do recognize the need for profound change and really the task for progressive movements is to convince people that change is possible. We must find ways to show that we're not so far gone, that we're not so hopeless, that we're not so corrupted, that we're not so greedy and that we still could act to save ourselves.

And that means social movements have their work cut out for them--for us. But that's the task, I feel.

And "ferocious love"--what's that?

Well, that was a phrase I wrote for the book, but it's related to a wonderful section of the book about frontline activists. I think one of the best quotes, if not the best quote in the book, is from [Montana goat farmer and anti-coal activist] Alexis Bonogofsky, where she says "Love will save this place."

That could have made a great title for the book.

Yeah... I could start crying just thinking about it.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

On the eve of the People's Climate March in New York City and parallel People's Climate Mobilization actions happening in thousands of locations across the planet on Sunday, author and activist Naomi Klein spoke with Common Dreams about the unique and profound historical moment that the crisis of climate change now presents for humanity.

Framed around some of the ideas presented in her new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, Klein talks about why she's optimistic for the future despite the unprecedented challenges that have for too long been ignored by world leaders, industrial elites, and even many of the world's hard-hitting economic and social justice advocates.

"Love will save this place..."

"I think there's this really powerful click going on for a lot of people who've been engaged in economic justice issues for a long time," Klein told Common Dreams. And now, she says, there's an enormous and growing number of people "really ready to jump into the climate fight with both feet" because "they know it's not somebody's else issue."

And the march in New York--now expected to draw well over 100,000 (and possibly twice that) to the streets of Manhattan --Klein argues is vital not because it will achieve anything in an immediate "linear" sense, but because it will powerfully help destroy the "cognitive dissonance of living in a culture where people are absorbing this terrifying news about the destabilization of our [planet]" on the one hand while on the other being surrounded "by messages from popular culture and political leaders who are acting as though nothing is happening."

People all over the world, says Klein, are showing that they now know nothing less than radical solutions will suffice and what these people, organizations, and communities will be saying collectively on Sunday is simple: "We see this as an emergency and we want to act."

Common Dreams: The cover of the new book makes a statement. First of all, it does not have two hands holding the earth or letters spelled out in leafy greens or flames of red. In fact, the letters are black and blue. We don't judge books by covers, of course, but any significance to those choices?

Naomi Klein: Well, there were other cover designs proposed. It was of those things where I knew what I didn't want, but I didn't know what I wanted. And then Scott Richardson, the artistic director at Random House Canada, designed this cover and as soon as I saw it I said, 'Yeah, that one.'

In terms of the black and blue --I don't know what you're implying (laughter)--but I love the optimism of the color and I just think it's a smart design because if climate change 'changes everything' then it should push everything else off the cover, including the subtitle and my name. It was interesting because it wasn't a no-brainer for the publisher, particularly for my American publisher, to go with such a risky cover design. But I'm really glad they decided to go with that. I think it was a brave move. It may backfire terribly -- as they pile up in remainder bins -- but that remains to be seen. I think that people like that it looks like a poster--or I least that's what I like about it.

What about the title? Was it clear to you that this was it early on in the project--or did it come at some specific moment along the way?

This project was actually really hard to name, in fact. It went through a few different names. With [my first book] No Logo I had that title right away, from before I even wrote it, whereas this book has gone through several titles. One way to say it is, I guess, is that I knew what I wanted the title to express, before I knew how to express it. The moment itself?... I was just walking home from yoga one day and it came to me.

"What I really think works about the title is that it starts the conversation where the conversation needs to start. "But, of course, its a name that's out there. But I think it's the combination of the subject and the name that's working. And what I really think works about the title is that it starts the conversation where the conversation needs to start.

The title starts the conversation with the idea that there are no non-radical solutions available to us -- that we've left the crisis unaddressed for too long -- so that now we're looking at radical physical change, radical engineering change, or radical economic/political change. And I think when that is put to people they kind of know that. And so that's what I like about it, is that starts the conversation in a good place.

You've said that the urgency of the climate crisis means that we have to break every rule in the free-market playbook. Are there also rules in the Left's playbook that have to be broken?

Yes. There are.

It's why I have a chapter in the book about extractivism as a worldview that is the hallmark of the post-industrial age and is common to both the left and the right, or has been traditionally. And that most of the big battles are not over whether we're going to have an extractivist relationship with the planet, acting as if resources are infinite or as if we don't need to think about the long-term consequences of our depletion of resources and our pollution. Instead, the battles are over really over the distribution of the spoils.

"So people who haven't read the book say, Is she saying that communism is good for the environment? And the answer is: I'm not."Certainly there is a Marxist critique of the ecological contradiction, but in terms of the real world application of those ideas--the way in which they were applied by centralized, industrial socialist states (or states that called themselves socialist)--those states were on the whole just as polluting, but also explicitly at war with nature. Quite literally, as we know, Mao had a "war against nature." And I say in the book that in the Soviet era emissions in the Eastern Bloc states were comparable or even higher than countries like Canada and Australia.

So people who haven't read the book say, "Is she saying that communism is good for the environment?" And the answer is: I'm not. And that's why I"m talking about a shift in worldview. And its a shift in worldview that is beginning and where you see it most starkly is in the conflicts between some of the left governments that have come to power in Latin America and the Indigenous-led movements that helped bring them to power. In [Bolivian President Evo] Morales' second term he's increasingly in conflict with that base over precisely this issue of an extractivist-based policy. And it's complicated because Morales is using the proceeds from his extractivist policies to fight poverty in a very real way. But there are also very real costs to those policies. And, of course, Venezuela is a pretty classic example.

But these conflicts are coming to a head in Brazil over dams; very strong conflicts in Ecuador over oil drilling in the Amazon -- so I think that this question, Does this require the Left to break some of its rules?, the answer is yes, because -- particularly in the United States, the Left is still very much in a Keynesian model, pursuing growth-based policies, it's just that they want to distribute the growth better.

You talk in separate sections of the book about two fetishes that strike you as troubling. One is the "fetish of centrism" that we see in elite policy circles and the "fetish of structurelessness" that exists elsewhere. Could you explain what you mean by both and how they play into the urgency of the climate crisis?

It's interesting because generally on the Left you have that sense of urgency, but that the idea that engaging with the state is so compromised that you can't do it is a barrier to winning political victories that can move us forward at the speed that we need to move forward. But I do see some signs of change on that front.

"I see now that this urgency -- both in the sense of austerity and the crisis of inequality and the ecological crisis -- is driving this generation of activists to get their hands dirty."I see, for instance, the Indignados movement in Spain having an offshoot political party, Podemos, which has a really visionary policy. And in Montreal, Canada, there's a political party there, called Solidaire, and its economic policies are incredibly strong and has environmental policies that directly connect acting on climate and opposing the tar sands and pipelines and opposing the austerity agenda. They have a really strong platform and they have three MPs and strong ties to social movements. And in the U.S., you have an occupy activist becoming a city councilor in Seattle and helping to win the victories for higher minimum wage.

And the example I write about in the book about Germany is a really interesting one in this context. Germany's green transition -- now being held up by pretty much everybody as one of the most staggering green transitions anywhere in the world, where in after a decade and a half they have 25 percent of their electricity coming from renewables and much of it decentralized--that was the result of a movement victory. That was the result of the fact that Germany has a very strong environmental movement, a very strong anti-nuclear movement, but it was a movement that has engaged with policy. And whether they're running for office is not the issue. They are helping to design policy and they are trying to defend that policy now against attempts to erode some of those victories for decentralization and efforts to bring in more big players. And that has something to do with the interplay between social movements, the Left parties, and Parliament -- but I don't think that the "fetish for structurelessness" and this kind of opting out of engaging with policy it was for my generation -- you know, for the Seattle generation. I see now that this urgency -- both in the sense of austerity and the crisis of inequality and the ecological crisis -- is driving this generation of activists to get their hands dirty. Which is good, I think. They're doing it better than we did.

And what about that connection between that anti-globalization movement that rose during the 1990's and the current climate justice movement that many of the same organizations and activists, yourself included, are now engaged so deeply with?

Well, the truth is, I don't think of them as separate issues or different movements. And in the book I talk about the connection between that globalization process that enabled multinationals to search the world for the cheapest possible labor was also simultaneously searching the world for the cheapest energy. Of course, it was. So of course the success of that model has coincided with an emissions explosion. And I think that it's maybe taken us a while to draw these very obvious connections and I think that part of that has to do with our own failures to just get in there on climate.

"I think that it's maybe taken us a while to draw these very obvious connections and I think that part of that has to do with our own failures to just get in there on climate."I think there was this sense, and I've said this before, that for many this was the one issue that you didn't have to deal with because it seem like all these very well-funded, green NGOs were taking care of it. And many people had a lot on their plate so in some ways it was kind of outsourced -- and that was a really bad idea. But I think part of it was also just this weird way in which the whole climate discourse pretended that globalization wasn't happening in that key period in which we were suppose to be fighting climate change.

For instance, in the accounting system that was established by the UN to stipulate which countries are responsible for which emissions, no country is accountable for the emissions associations with transportation of goods across borders. So all of those freighter ships filled with goods, crossing the oceans, nobody is responsible for those emissions. And that's amazing. Or the fact that we have a system in which countries are responsible for the emissions associated with the goods that we consume, but not the emissions that go into producing or transporting those goods to us, across borders. So the television in your living room, that was made in China, you are accountable for the emissions that go in to turning it on and watching it, but none of the emissions that went into making it are transporting it. The emissions that went into making it are on China's bill and the emissions that went into transporting across the ocean went onto no one's bill.

This all represents, I think, this weird myopia and unwillingness to engage with some of these blatant contradictions between what was going on in the climate negotiations and what was going on simultaneously in the trade negotiations. And now, we see that they were clearly in conflict, because emissions are going up associated with that so-called free-trade explosion and that whole model, but also because many of the things we need to do to get off fossil fuels are being ruled illegal by the World Trade Organization and under agreements like NAFTA.

What are 'Beautiful Solutions'?

Well, I call this a project not a book because while I've been writing the book, my husband Avi Lewis -- who has worked in television for many years for the CBC and Al Jazeera and we also made a documentary together called The Take -- has been making a documentary film on the same topic. So it's not an adaptation of the book, because we've working on this in parallel -- but as I've been writing the book, he's been making this film. And there are points of intersection where we've documented the same thing. For instance, we went to Montana and I documented the fight against coal mining and some of the people doing incredible work, but you'll also meet them in the movie. And this makes me really happy, because maybe in the book there might be one or two quotes from them but in the film they're actual real people and you go to their house, you get to know them and they're amazing. So I think that's really great.

So Avi's going to be coming out with this film in January and we put way more thought into this project than we've been able to in the past. We both see our work as being tools for movements. We believe that the culture we produce should be part of the project of social change--that's what we want anyway. But we've always done this in a pretty ad hoc way. I've always just kind of gotten lucky, you know. No Logo came out just as the Seattle protests were happening and I just got swept up in that wave. And with The Take we had this great experience of the film being screened inside occupied factories and could see it being used as a tool for workers considering forming co-ops and things like that.

"We want to use these moments, to the extent that we can, to open up spaces for the movements that we are working with--and that our work would be impossible without--to speak for themselves."But with this project on climate change we wanted to do it in a more deliberate way. And so we've had something akin to outreach or an engagement strategy from the beginning -- from the earliest days -- where we've been having meetings with the social movements that I'm writing about and that Avi has been filming. And we've talked about how the cultural moments that sometimes come along with the writing of a book or the making of a film can be of more help to movements.

This weekend, for instance, ahead of the People's Climate March in New York we're hosting a summit with a bunch of the climate groups that are in town and one of the things we're going to be talking about -- once the film is done -- is having a series of teach-ins that can be useful to these organizations' members. So part of this project is that we've launched this website and we've partnered with a great editorial team that previously put together a book called "Beautiful Trouble," which looks at resistance strategies. And the next logical step for them was a project called "Beautiful Solutions" where they're documenting the real-world solutions that are emerging, particularly in frontline communities. That book isn't published yet, but they are pre-publishing a bunch of their stuff on the website. So they aren't us and we're aren't them, but we've partnered for this project and we're really excited about both the partnership and the work.

There can be a weird thing that happens when a book gets published -- you know, I've been lucky with my books and I get a certain amount of media attention -- so we want to use these moments, to the extent that we can, to open up spaces for the movements that we are working with--and that our work would be impossible without--to speak for themselves. That's why a few nights ago, at my book launch in New York, you know, I spoke for twenty minutes (not forty-five minutes) and then we had a great panel discussion with some of the terrific climate justice activists from the labor movement and the Indigenous rights movement and people like Esperanza Martinez--who I quote in my book --from Accion Ecologica in Ecuador. This is kind of the model that we're trying to figure out.

So you've had a week now (perhaps more) to talk in depth about your book... and now you're in New York on the eve of the People's Climate March & Mobilization (billed as the "largest climate mobilization in the history of the world") and the Flood Wall Street event in the financial district on Monday. How are you feeling? What are seeing? What's been most striking so far?

I just feel there's this really powerful "click" going on for a lot of people who've been engaged in economic justice issues for a long time. They are now really ready to jump into the climate fight with both feet and they know it's not somebody's else issue. And a lot of friends of mine who for a long time who kind of said, "Oh, that's your thing" or "I know you're doing this climate thing now, but I'll see you afterwards." -- those people are now saying, "Yeah. Of course, I'm going."

"We must find ways to show that we're not so far gone, that we're not so hopeless, that we're not so corrupted, that we're not so greedy and that we still could act to save ourselves."We're talking before the march, but I've got a feeling it's gonna be huge. And I know there's a been a debate about 'Who's marching?' or whether it means anything, but I just think the experience of just seeing how many people feel passionately about this issue is going to be so important to break that sense of isolation and just the cognitive dissonance of living in a culture where you are absorbing this terrifying news about the destabilization of our home, on the one hand, and to be surrounding by messages from popular culture and our political leaders who are acting as though nothing is happening. So I think there's something really important about moments of coming together to say, 'No. We see this as an emergency and we want to act."

So I don't think it's about whether this march is going to accomplish something linear, but I do think that it's going to nourish this movement in a really important way.

And what I have found most striking as I've been talking to journalists for the last couple of weeks is that I was so prepared to have people challenge me about how radical the conclusions are or how radical the changes have to be. Or maybe disagree with me science isn't that alarming. My amazing researchers and I spent a lot of time anticipating those kinds of attacks. But what's actually happened is that I've spent most of my time talking to journalists who want to argue with me about whether there's any hope at all. So they're agreeing with the conclusions about the need for radical change, and what they disagree with is the idea that there's any hope at all.

So I think it's a pretty extraordinary political moment. And where so many people do recognize the need for profound change and really the task for progressive movements is to convince people that change is possible. We must find ways to show that we're not so far gone, that we're not so hopeless, that we're not so corrupted, that we're not so greedy and that we still could act to save ourselves.

And that means social movements have their work cut out for them--for us. But that's the task, I feel.

And "ferocious love"--what's that?

Well, that was a phrase I wrote for the book, but it's related to a wonderful section of the book about frontline activists. I think one of the best quotes, if not the best quote in the book, is from [Montana goat farmer and anti-coal activist] Alexis Bonogofsky, where she says "Love will save this place."

That could have made a great title for the book.

Yeah... I could start crying just thinking about it.

On the eve of the People's Climate March in New York City and parallel People's Climate Mobilization actions happening in thousands of locations across the planet on Sunday, author and activist Naomi Klein spoke with Common Dreams about the unique and profound historical moment that the crisis of climate change now presents for humanity.

Framed around some of the ideas presented in her new book, This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. The Climate, Klein talks about why she's optimistic for the future despite the unprecedented challenges that have for too long been ignored by world leaders, industrial elites, and even many of the world's hard-hitting economic and social justice advocates.

"Love will save this place..."

"I think there's this really powerful click going on for a lot of people who've been engaged in economic justice issues for a long time," Klein told Common Dreams. And now, she says, there's an enormous and growing number of people "really ready to jump into the climate fight with both feet" because "they know it's not somebody's else issue."

And the march in New York--now expected to draw well over 100,000 (and possibly twice that) to the streets of Manhattan --Klein argues is vital not because it will achieve anything in an immediate "linear" sense, but because it will powerfully help destroy the "cognitive dissonance of living in a culture where people are absorbing this terrifying news about the destabilization of our [planet]" on the one hand while on the other being surrounded "by messages from popular culture and political leaders who are acting as though nothing is happening."

People all over the world, says Klein, are showing that they now know nothing less than radical solutions will suffice and what these people, organizations, and communities will be saying collectively on Sunday is simple: "We see this as an emergency and we want to act."

Common Dreams: The cover of the new book makes a statement. First of all, it does not have two hands holding the earth or letters spelled out in leafy greens or flames of red. In fact, the letters are black and blue. We don't judge books by covers, of course, but any significance to those choices?

Naomi Klein: Well, there were other cover designs proposed. It was of those things where I knew what I didn't want, but I didn't know what I wanted. And then Scott Richardson, the artistic director at Random House Canada, designed this cover and as soon as I saw it I said, 'Yeah, that one.'

In terms of the black and blue --I don't know what you're implying (laughter)--but I love the optimism of the color and I just think it's a smart design because if climate change 'changes everything' then it should push everything else off the cover, including the subtitle and my name. It was interesting because it wasn't a no-brainer for the publisher, particularly for my American publisher, to go with such a risky cover design. But I'm really glad they decided to go with that. I think it was a brave move. It may backfire terribly -- as they pile up in remainder bins -- but that remains to be seen. I think that people like that it looks like a poster--or I least that's what I like about it.

What about the title? Was it clear to you that this was it early on in the project--or did it come at some specific moment along the way?

This project was actually really hard to name, in fact. It went through a few different names. With [my first book] No Logo I had that title right away, from before I even wrote it, whereas this book has gone through several titles. One way to say it is, I guess, is that I knew what I wanted the title to express, before I knew how to express it. The moment itself?... I was just walking home from yoga one day and it came to me.

"What I really think works about the title is that it starts the conversation where the conversation needs to start. "But, of course, its a name that's out there. But I think it's the combination of the subject and the name that's working. And what I really think works about the title is that it starts the conversation where the conversation needs to start.

The title starts the conversation with the idea that there are no non-radical solutions available to us -- that we've left the crisis unaddressed for too long -- so that now we're looking at radical physical change, radical engineering change, or radical economic/political change. And I think when that is put to people they kind of know that. And so that's what I like about it, is that starts the conversation in a good place.

You've said that the urgency of the climate crisis means that we have to break every rule in the free-market playbook. Are there also rules in the Left's playbook that have to be broken?

Yes. There are.

It's why I have a chapter in the book about extractivism as a worldview that is the hallmark of the post-industrial age and is common to both the left and the right, or has been traditionally. And that most of the big battles are not over whether we're going to have an extractivist relationship with the planet, acting as if resources are infinite or as if we don't need to think about the long-term consequences of our depletion of resources and our pollution. Instead, the battles are over really over the distribution of the spoils.

"So people who haven't read the book say, Is she saying that communism is good for the environment? And the answer is: I'm not."Certainly there is a Marxist critique of the ecological contradiction, but in terms of the real world application of those ideas--the way in which they were applied by centralized, industrial socialist states (or states that called themselves socialist)--those states were on the whole just as polluting, but also explicitly at war with nature. Quite literally, as we know, Mao had a "war against nature." And I say in the book that in the Soviet era emissions in the Eastern Bloc states were comparable or even higher than countries like Canada and Australia.

So people who haven't read the book say, "Is she saying that communism is good for the environment?" And the answer is: I'm not. And that's why I"m talking about a shift in worldview. And its a shift in worldview that is beginning and where you see it most starkly is in the conflicts between some of the left governments that have come to power in Latin America and the Indigenous-led movements that helped bring them to power. In [Bolivian President Evo] Morales' second term he's increasingly in conflict with that base over precisely this issue of an extractivist-based policy. And it's complicated because Morales is using the proceeds from his extractivist policies to fight poverty in a very real way. But there are also very real costs to those policies. And, of course, Venezuela is a pretty classic example.

But these conflicts are coming to a head in Brazil over dams; very strong conflicts in Ecuador over oil drilling in the Amazon -- so I think that this question, Does this require the Left to break some of its rules?, the answer is yes, because -- particularly in the United States, the Left is still very much in a Keynesian model, pursuing growth-based policies, it's just that they want to distribute the growth better.

You talk in separate sections of the book about two fetishes that strike you as troubling. One is the "fetish of centrism" that we see in elite policy circles and the "fetish of structurelessness" that exists elsewhere. Could you explain what you mean by both and how they play into the urgency of the climate crisis?

It's interesting because generally on the Left you have that sense of urgency, but that the idea that engaging with the state is so compromised that you can't do it is a barrier to winning political victories that can move us forward at the speed that we need to move forward. But I do see some signs of change on that front.

"I see now that this urgency -- both in the sense of austerity and the crisis of inequality and the ecological crisis -- is driving this generation of activists to get their hands dirty."I see, for instance, the Indignados movement in Spain having an offshoot political party, Podemos, which has a really visionary policy. And in Montreal, Canada, there's a political party there, called Solidaire, and its economic policies are incredibly strong and has environmental policies that directly connect acting on climate and opposing the tar sands and pipelines and opposing the austerity agenda. They have a really strong platform and they have three MPs and strong ties to social movements. And in the U.S., you have an occupy activist becoming a city councilor in Seattle and helping to win the victories for higher minimum wage.

And the example I write about in the book about Germany is a really interesting one in this context. Germany's green transition -- now being held up by pretty much everybody as one of the most staggering green transitions anywhere in the world, where in after a decade and a half they have 25 percent of their electricity coming from renewables and much of it decentralized--that was the result of a movement victory. That was the result of the fact that Germany has a very strong environmental movement, a very strong anti-nuclear movement, but it was a movement that has engaged with policy. And whether they're running for office is not the issue. They are helping to design policy and they are trying to defend that policy now against attempts to erode some of those victories for decentralization and efforts to bring in more big players. And that has something to do with the interplay between social movements, the Left parties, and Parliament -- but I don't think that the "fetish for structurelessness" and this kind of opting out of engaging with policy it was for my generation -- you know, for the Seattle generation. I see now that this urgency -- both in the sense of austerity and the crisis of inequality and the ecological crisis -- is driving this generation of activists to get their hands dirty. Which is good, I think. They're doing it better than we did.

And what about that connection between that anti-globalization movement that rose during the 1990's and the current climate justice movement that many of the same organizations and activists, yourself included, are now engaged so deeply with?

Well, the truth is, I don't think of them as separate issues or different movements. And in the book I talk about the connection between that globalization process that enabled multinationals to search the world for the cheapest possible labor was also simultaneously searching the world for the cheapest energy. Of course, it was. So of course the success of that model has coincided with an emissions explosion. And I think that it's maybe taken us a while to draw these very obvious connections and I think that part of that has to do with our own failures to just get in there on climate.

"I think that it's maybe taken us a while to draw these very obvious connections and I think that part of that has to do with our own failures to just get in there on climate."I think there was this sense, and I've said this before, that for many this was the one issue that you didn't have to deal with because it seem like all these very well-funded, green NGOs were taking care of it. And many people had a lot on their plate so in some ways it was kind of outsourced -- and that was a really bad idea. But I think part of it was also just this weird way in which the whole climate discourse pretended that globalization wasn't happening in that key period in which we were suppose to be fighting climate change.

For instance, in the accounting system that was established by the UN to stipulate which countries are responsible for which emissions, no country is accountable for the emissions associations with transportation of goods across borders. So all of those freighter ships filled with goods, crossing the oceans, nobody is responsible for those emissions. And that's amazing. Or the fact that we have a system in which countries are responsible for the emissions associated with the goods that we consume, but not the emissions that go into producing or transporting those goods to us, across borders. So the television in your living room, that was made in China, you are accountable for the emissions that go in to turning it on and watching it, but none of the emissions that went into making it are transporting it. The emissions that went into making it are on China's bill and the emissions that went into transporting across the ocean went onto no one's bill.

This all represents, I think, this weird myopia and unwillingness to engage with some of these blatant contradictions between what was going on in the climate negotiations and what was going on simultaneously in the trade negotiations. And now, we see that they were clearly in conflict, because emissions are going up associated with that so-called free-trade explosion and that whole model, but also because many of the things we need to do to get off fossil fuels are being ruled illegal by the World Trade Organization and under agreements like NAFTA.

What are 'Beautiful Solutions'?

Well, I call this a project not a book because while I've been writing the book, my husband Avi Lewis -- who has worked in television for many years for the CBC and Al Jazeera and we also made a documentary together called The Take -- has been making a documentary film on the same topic. So it's not an adaptation of the book, because we've working on this in parallel -- but as I've been writing the book, he's been making this film. And there are points of intersection where we've documented the same thing. For instance, we went to Montana and I documented the fight against coal mining and some of the people doing incredible work, but you'll also meet them in the movie. And this makes me really happy, because maybe in the book there might be one or two quotes from them but in the film they're actual real people and you go to their house, you get to know them and they're amazing. So I think that's really great.

So Avi's going to be coming out with this film in January and we put way more thought into this project than we've been able to in the past. We both see our work as being tools for movements. We believe that the culture we produce should be part of the project of social change--that's what we want anyway. But we've always done this in a pretty ad hoc way. I've always just kind of gotten lucky, you know. No Logo came out just as the Seattle protests were happening and I just got swept up in that wave. And with The Take we had this great experience of the film being screened inside occupied factories and could see it being used as a tool for workers considering forming co-ops and things like that.

"We want to use these moments, to the extent that we can, to open up spaces for the movements that we are working with--and that our work would be impossible without--to speak for themselves."But with this project on climate change we wanted to do it in a more deliberate way. And so we've had something akin to outreach or an engagement strategy from the beginning -- from the earliest days -- where we've been having meetings with the social movements that I'm writing about and that Avi has been filming. And we've talked about how the cultural moments that sometimes come along with the writing of a book or the making of a film can be of more help to movements.

This weekend, for instance, ahead of the People's Climate March in New York we're hosting a summit with a bunch of the climate groups that are in town and one of the things we're going to be talking about -- once the film is done -- is having a series of teach-ins that can be useful to these organizations' members. So part of this project is that we've launched this website and we've partnered with a great editorial team that previously put together a book called "Beautiful Trouble," which looks at resistance strategies. And the next logical step for them was a project called "Beautiful Solutions" where they're documenting the real-world solutions that are emerging, particularly in frontline communities. That book isn't published yet, but they are pre-publishing a bunch of their stuff on the website. So they aren't us and we're aren't them, but we've partnered for this project and we're really excited about both the partnership and the work.

There can be a weird thing that happens when a book gets published -- you know, I've been lucky with my books and I get a certain amount of media attention -- so we want to use these moments, to the extent that we can, to open up spaces for the movements that we are working with--and that our work would be impossible without--to speak for themselves. That's why a few nights ago, at my book launch in New York, you know, I spoke for twenty minutes (not forty-five minutes) and then we had a great panel discussion with some of the terrific climate justice activists from the labor movement and the Indigenous rights movement and people like Esperanza Martinez--who I quote in my book --from Accion Ecologica in Ecuador. This is kind of the model that we're trying to figure out.

So you've had a week now (perhaps more) to talk in depth about your book... and now you're in New York on the eve of the People's Climate March & Mobilization (billed as the "largest climate mobilization in the history of the world") and the Flood Wall Street event in the financial district on Monday. How are you feeling? What are seeing? What's been most striking so far?

I just feel there's this really powerful "click" going on for a lot of people who've been engaged in economic justice issues for a long time. They are now really ready to jump into the climate fight with both feet and they know it's not somebody's else issue. And a lot of friends of mine who for a long time who kind of said, "Oh, that's your thing" or "I know you're doing this climate thing now, but I'll see you afterwards." -- those people are now saying, "Yeah. Of course, I'm going."

"We must find ways to show that we're not so far gone, that we're not so hopeless, that we're not so corrupted, that we're not so greedy and that we still could act to save ourselves."We're talking before the march, but I've got a feeling it's gonna be huge. And I know there's a been a debate about 'Who's marching?' or whether it means anything, but I just think the experience of just seeing how many people feel passionately about this issue is going to be so important to break that sense of isolation and just the cognitive dissonance of living in a culture where you are absorbing this terrifying news about the destabilization of our home, on the one hand, and to be surrounding by messages from popular culture and our political leaders who are acting as though nothing is happening. So I think there's something really important about moments of coming together to say, 'No. We see this as an emergency and we want to act."

So I don't think it's about whether this march is going to accomplish something linear, but I do think that it's going to nourish this movement in a really important way.

And what I have found most striking as I've been talking to journalists for the last couple of weeks is that I was so prepared to have people challenge me about how radical the conclusions are or how radical the changes have to be. Or maybe disagree with me science isn't that alarming. My amazing researchers and I spent a lot of time anticipating those kinds of attacks. But what's actually happened is that I've spent most of my time talking to journalists who want to argue with me about whether there's any hope at all. So they're agreeing with the conclusions about the need for radical change, and what they disagree with is the idea that there's any hope at all.

So I think it's a pretty extraordinary political moment. And where so many people do recognize the need for profound change and really the task for progressive movements is to convince people that change is possible. We must find ways to show that we're not so far gone, that we're not so hopeless, that we're not so corrupted, that we're not so greedy and that we still could act to save ourselves.

And that means social movements have their work cut out for them--for us. But that's the task, I feel.

And "ferocious love"--what's that?

Well, that was a phrase I wrote for the book, but it's related to a wonderful section of the book about frontline activists. I think one of the best quotes, if not the best quote in the book, is from [Montana goat farmer and anti-coal activist] Alexis Bonogofsky, where she says "Love will save this place."

That could have made a great title for the book.

Yeah... I could start crying just thinking about it.