When will students and recent college graduates shake off the burden of increasingly higher student debt and demand a system that serves them instead of making them servants?

The amount of personal debt being accrued by college students in the nation's private and public colleges continues to rise at shocking rates with current graduates of four-year schools exiting with a national average of nearly $30,000 in loans to repay, according to a new report released Thursday.

"To put it bluntly, there is no fiscal reason why the U.S. student debt crisis should exist."

--Raul Carrillo, Modern Money Network

Using available data from private non-profit and public schools in all fifty states for the 2013 academic year, the Project on Student Debt at The Institute for College Access & Success (TICAS) found that the level of debt varies from state to state, but that of the nearly 70 percent of graduates who take out a loan to pay for colllege, the burden continues to grow. According to the report (pdf), the average bachelor-degree graduate--along with a diploma of increasingly questionable value-- leaves school with and an average of $28,400 in personal debt. That number is a full 2 percent increase over 2012.

Notably, for-profit colleges--which have been widely criticized for burdening vulnerable students with out-sized private debt--were not included in the TICAS report because those schools nearly universally decline to share their student loan and debt figures with the public.

Among the schools that were covered, however, there was clear variation in the level of student debt depending on the college itself and its geographic location.

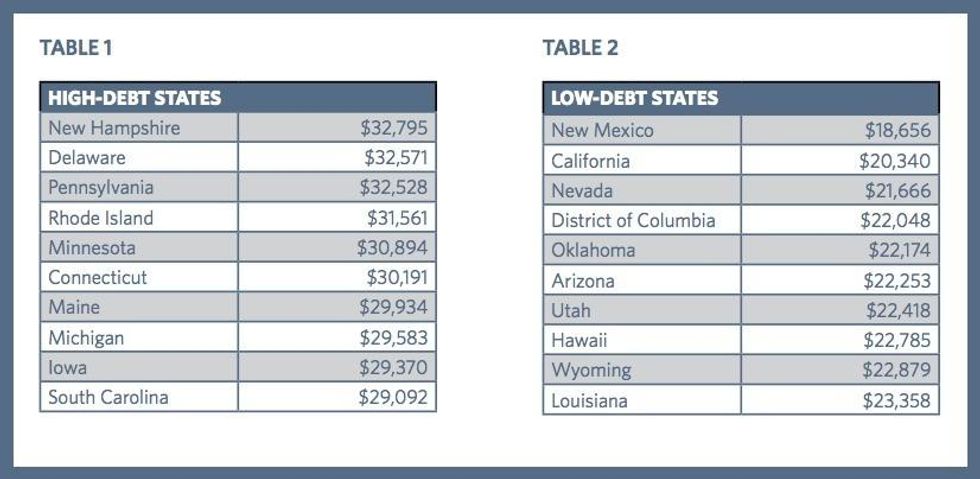

At nearly 20 percent of colleges, the report showed, average debt levels for students increased by 10 percent or more over the previous year. As in 2012, about 20 percent of all new graduates' debt was in private loans, which are typically more costly and provide far fewer consumer protections and repayment options than safer federal student loans. The rate of debt also varied between states. "At the state level," the report reads, "borrowers' average debt at graduation ranges from $18,656 to $32,795, with six states topping $30,000 and only one under $20,000. Nearly all the highest debt states are in the Northeast and Midwest, with the lowest debt states in the West and South."

In a separate but related study released on Wednesday, new research and polling that focused on the financial burdens of higher-education among recent college graduates--titled Millennials & College Planning--found that today's students are increasingly "having to let finances dictate their futures."

"One-third of those with student loans are shelling out over $300 per month and five percent are actually paying more than $1000 per month."

The report, coordinated by Junior Achievement USA and PwC US and prepared by New York-based research firm YPulse, found several key trends among recent graduates (aged 18-29), including:

- For 60 percent of Millennials, financial aid is a deciding factor in their school choice. Among those not attending their first choice school this year, 62 percent said it was because they couldn't afford it.

- College tuition and loans top the list of money matters that are worrying Millennials ages 18-29, with one in five (21 percent) claiming it as their family's main financial problem.

- One-third of those students with loans are shelling out over $300 per month and five percent are actually paying more than $1000 per month.

- Nearly one-in-four Millennials (24 percent) believe their student loan debt will ultimately be forgiven.

Though told by society that the key to a bright and prosperous future is largely dependent on getting a degree, the new generation is becoming increasingly skeptical of that claim. According to the authors of this report: "While high school graduates are hard-pressed to find gainful employment with just a diploma, we see a new Catch-22 emerging: As the number of people attending college increases, the value of its education decreases. Some Millennials say 'a four-year college degree isn't as valuable as it used to be,' but continue with their higher education in order to have a real chance in the job market."

And though the survey section of the report, as noted, asked graduates about the idea of loan or debt "forgiveness," the report itself does not delve into the issue with any detail.

Forgive all student debt? Why not, says Common Dreams contributor Robert Shetterly, who in an essay on the subject posted Thursday says it is time to break the chains that student loan debt has placed on a generation of young people. As the portrait artist and writer explains:

Thom Hartmann points out that the best thing this country could do is forgive all--all $1.18 trillion!--in student debt because it would repay the country many times over. The huge expense of the GI Bill after WW II was a great investment for the government; better educated vets got better jobs, were more entrepreneurial, and paid taxes worth significantly more than the cost of the program. Hartmann says we have created a "lost generation" of debt-saddled, young people lost not only to themselves but unable to help build a more vibrant country. He calls for a Jubilee of Debt Forgiveness that would trigger an American Renaissance of young people free to be creative, take risks, explore ideas and lives without owing a pound of flesh to the banks. So we write off $ 1 trillion? Why not? The Iraq War will cost several times that when it's finally tallied up. What benefits to society did it bring? Unless you have a lot of stock in Halliburton or Lockheed Martin, it would be hard to name a single plus.

One trillion given to students and the promise of free higher education would revitalize this country and be repaid many times over. Our country's greatest asset is the energy and creativity of our young people. Why allow that energy to be siphoned off to increase the wealth of a handful of millionaires? Isn't that a form of cultural suicide?

More importantly, forgiving this debt and creating a free educational system would signal a change in values. We've allowed this country to favor the market and the making of profit over every other value. We have been sacrificing the lives of our children and the benefits they can offer to the health of a democratic society by shackling them to debt, turning them into another natural resource to be mined for profit. Our survival as a nation and as a species depends not on profit but on creativity.

However, in a piece written for YES! Magazine, also published this week, Raul Carrillo, co-organizer for The Modern Money Network (MMN), offered a solution that goes beyond debt forgiveness by arguing that instead of private or publicly funded college loans, the federal government should simply pay the tuition for those seeking high-education.

"To put it bluntly," writes Carrillo, "there is no fiscal reason why the U.S. student debt crisis should exist."

"You may find this argument hard to believe," he continues, recognizing that "the way most politicians and journalists talk about the national debt and deficit spending makes free higher education sound impossible." Carillo says there's another way of looking at the crisis of student debt and funding of higher education--"a vision advocated by a growing movement of economists, lawyers, students, and financial practitioners who deal with the institutional nuts and bolts of the economy on a day-to-day basis."

In simplest terms, Carillo's argument rests on the idea that the U.S. federal government, capable of printing its own money, is simply "not broke" in the way that deficit hawks, who always find money for war and prisons and tax breaks for corporations, say it is. The demand should be that government print money into existence on behalf something good, a public investment, like education. He writes:

If money should be owed for higher education at all, perhaps the federal government should owe us. After all, Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution entrusts the federal government with a monopoly to create, spend, and regulate money for the "general welfare of the United States." And in the era of modern money, there's no good economic reason for students' pockets to be so shallow when the government's are so deep.

When the federal government lists a deficit, that indicates a surplus for American citizens, as well as foreign businesses that sell us goods. In other words, the government's red ink is the public's black ink. Despite what organizations with wholesome and appealing names like Fix the Debt, The Can Kicks Back, and Up To Us, might claim, the "national debt" is not a burden for young people. Indeed, advocating for smaller federal deficits hurts student debtors. Even in the future, it offers them no tangible benefits.

As the Nobel-winning economist Paul Samuelson once acknowledged, the "superstition" that the budget must be balanced at all times is part of an "old fashioned religion," meant to hush people who might otherwise demand the government create more money. Young people should beware of anyone who tells them that their chief worry for the future is the government's debt, rather than their own.