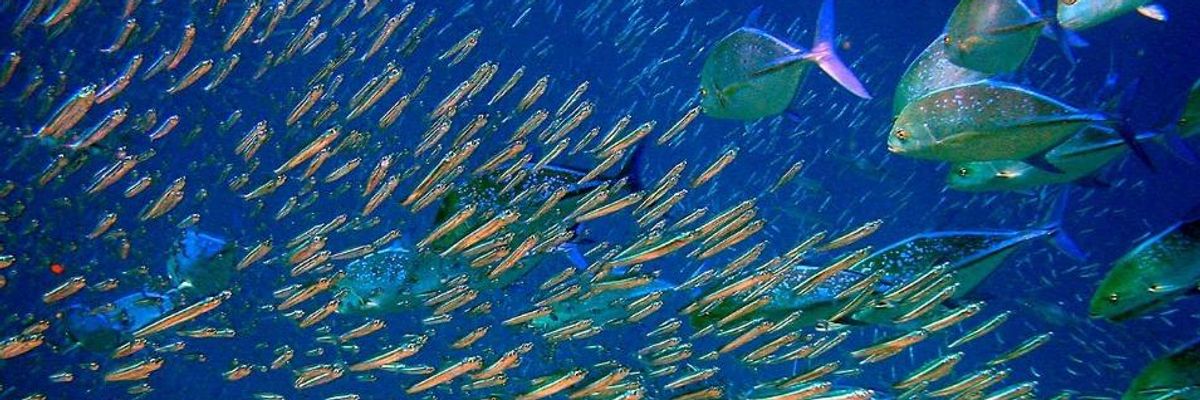

Mass die-offs of birds, fish, and marine invertebrates have grown increasingly frequent and severe, hiking at a rate of approximately one major mortality event per year over the past seven decades, according to a new study published by Yale, UC Berkeley, and University of San Diego researchers.

"While this might not seem like much, one additional mass mortality event per year over 70 years translates into a considerable increase in the number of these events being reported each year," said study co-lead author Adam Siepielski, an assistant professor of biology at the University of San Diego, in a statement about the study, which was published earlier this month in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"Going from one event to 70 each year is a substantial increase, especially given the increased magnitudes of mass mortality events for some of these organisms, Siepielski added.

The researchers define mass mortality events as "rapidly occurring catastrophic demographic events" that eliminate more than 90 percent of a population, kill more than a billion animals, or produce "700 million tons of dead biomass in a single event." For the study, they evaluated 727 mass die-offs of almost 2,500 animal species since 1940.

"This is the first attempt to quantify patterns in the frequency, magnitude and cause of such mass kill events," said study senior author Stephanie Carlson, an associate professor at the University of California, Berkeley's Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management.

The researchers concluded that, even when they account for improvements in reporting such mass die-off events, there is still an increase for birds, fish, and marine invertebrates.

Disease is responsible for 26 percent of such die-offs, making it the number one cause over the past 70 years. Direct human impact on the environment, including contamination, comes in a close second at 19 percent. Furthermore, a report summary notes, "Biotoxicity triggered by events such as algae blooms accounted for a significant proportion of deaths, and processes directly influenced by climate -- including weather extremes, thermal stress, oxygen stress or starvation -- collectively contributed to about 25 percent of mass mortality events."

According to the study, the mass kill events of the greatest magnitude "were those that resulted from multiple stressors, starvation, and disease."

Carlson explained, "In our studies, we have come across mass kills of federal fish species during the summer drought season as small streams dry up. The majority of studies we reviewed were of fish. When oxygen levels are depressed in the water column, the impact can affect a variety of species."

However, the report concludes that mass die-offs involving mammals appear to be unchanged, while the frequency of such events with respect to reptiles and amphibians appears to be decreasing.