SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

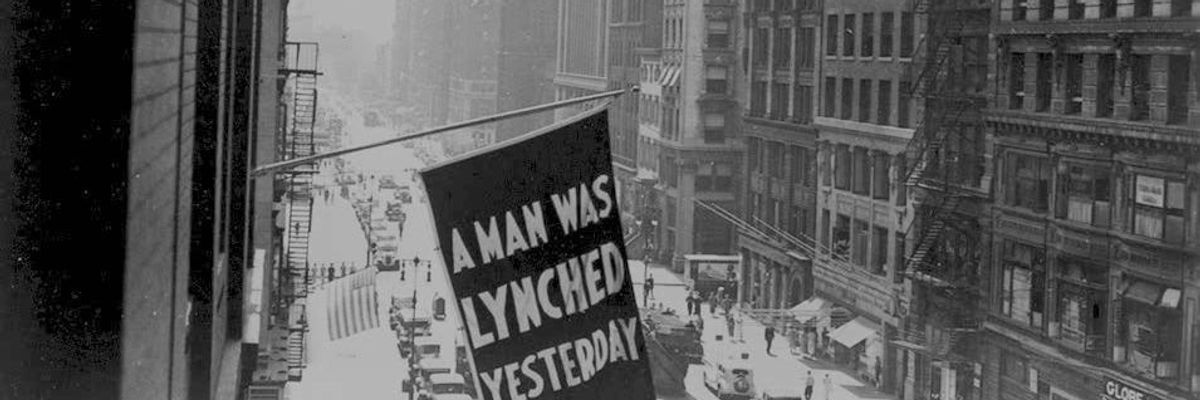

A flag announcing a lynching hangs from the window of the NAACP headquarters on 69 Fifth Ave., New York City. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Capital punishment and ongoing racial injustice in the United States are "direct descendents" of lynching, charges a new study, which found that the pre-World War II practice of "racial terrorism" has had a much more profound impact on race relations in America than previously acknowledged.

The most comprehensive work done on lynching to date, the investigation unearthed a total of 3,959 racially-motivated lynchings during the period between Reconstruction and World War II, which is at least 700 more killings than previously reported.

The report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror (pdf), published Tuesday by the legal nonprofit Equal Justice Institute (EJI), culminates the group's multi-year investigation into lynching in twelve Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia) during that period.

These killings, EJI charges, are a form of terrorism. The "violent and public acts of torture" were widely tolerated, particularly by state and federal officials, and "created a fearful environment where racial subordination and segregation was maintained with limited resistance for decades."

"The failings of this era very much reflect what young people are now saying about police shootings," EJI Director Bryan Stevenson told the Guardian, connecting the widespread acceptance of lynchings historically with the current racial justice movement. "It is about embracing this idea that 'black lives matter.'"

Stevenson continued: "I also think that the lynching era created a narrative of racial difference, a presumption of guilt, a presumption of dangerousness that got assigned to African Americans in particular--and that's the same presumption of guilt that burdens young kids living in urban areas who are sometimes menaced, threatened, or shot and killed by law enforcement officers."

The report documents a number of cases where black individuals were tortured and murdered, often in front of spectators, for such "crimes" as bumping into a white person, wearing their military uniforms after World War I, or not using the appropriate title when addressing a white person.

The report further suggests that the decline of lynching was tied to the rise of capital punishment--"a more palatable form of violence."

Capital punishment, the authors say, remains "rooted in racial terror" and is a "direct descendant of lynching."

Between 1910 and 1950, African Americans fell to just 22 percent of the South's population but constituted 75 percent of those executed there during that time. And today, African Americans compromise less than 13 percent of the nation's population but nearly 42 percent of those currently on death row in America.

The report continues: "Modern death sentences are disproportionately meted out to African Americans accused of crimes against white victims; efforts to combat racial bias and create federal protection against racial bias in the administration of the death penalty remain thwarted by familiar appeals to the rhetoric of states' rights; and regional data demonstrates that the modern death penalty in America mirrors racial violence of the past."

The authors hope that by confronting the reality of the country's racial history, Americans can work toward addressing the contemporary problems that are lynching's legacy.

"We cannot heal the deep wounds inflicted during the era of racial terrorism until we tell the truth about it," Stevenson said.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

Capital punishment and ongoing racial injustice in the United States are "direct descendents" of lynching, charges a new study, which found that the pre-World War II practice of "racial terrorism" has had a much more profound impact on race relations in America than previously acknowledged.

The most comprehensive work done on lynching to date, the investigation unearthed a total of 3,959 racially-motivated lynchings during the period between Reconstruction and World War II, which is at least 700 more killings than previously reported.

The report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror (pdf), published Tuesday by the legal nonprofit Equal Justice Institute (EJI), culminates the group's multi-year investigation into lynching in twelve Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia) during that period.

These killings, EJI charges, are a form of terrorism. The "violent and public acts of torture" were widely tolerated, particularly by state and federal officials, and "created a fearful environment where racial subordination and segregation was maintained with limited resistance for decades."

"The failings of this era very much reflect what young people are now saying about police shootings," EJI Director Bryan Stevenson told the Guardian, connecting the widespread acceptance of lynchings historically with the current racial justice movement. "It is about embracing this idea that 'black lives matter.'"

Stevenson continued: "I also think that the lynching era created a narrative of racial difference, a presumption of guilt, a presumption of dangerousness that got assigned to African Americans in particular--and that's the same presumption of guilt that burdens young kids living in urban areas who are sometimes menaced, threatened, or shot and killed by law enforcement officers."

The report documents a number of cases where black individuals were tortured and murdered, often in front of spectators, for such "crimes" as bumping into a white person, wearing their military uniforms after World War I, or not using the appropriate title when addressing a white person.

The report further suggests that the decline of lynching was tied to the rise of capital punishment--"a more palatable form of violence."

Capital punishment, the authors say, remains "rooted in racial terror" and is a "direct descendant of lynching."

Between 1910 and 1950, African Americans fell to just 22 percent of the South's population but constituted 75 percent of those executed there during that time. And today, African Americans compromise less than 13 percent of the nation's population but nearly 42 percent of those currently on death row in America.

The report continues: "Modern death sentences are disproportionately meted out to African Americans accused of crimes against white victims; efforts to combat racial bias and create federal protection against racial bias in the administration of the death penalty remain thwarted by familiar appeals to the rhetoric of states' rights; and regional data demonstrates that the modern death penalty in America mirrors racial violence of the past."

The authors hope that by confronting the reality of the country's racial history, Americans can work toward addressing the contemporary problems that are lynching's legacy.

"We cannot heal the deep wounds inflicted during the era of racial terrorism until we tell the truth about it," Stevenson said.

Capital punishment and ongoing racial injustice in the United States are "direct descendents" of lynching, charges a new study, which found that the pre-World War II practice of "racial terrorism" has had a much more profound impact on race relations in America than previously acknowledged.

The most comprehensive work done on lynching to date, the investigation unearthed a total of 3,959 racially-motivated lynchings during the period between Reconstruction and World War II, which is at least 700 more killings than previously reported.

The report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror (pdf), published Tuesday by the legal nonprofit Equal Justice Institute (EJI), culminates the group's multi-year investigation into lynching in twelve Southern states (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia) during that period.

These killings, EJI charges, are a form of terrorism. The "violent and public acts of torture" were widely tolerated, particularly by state and federal officials, and "created a fearful environment where racial subordination and segregation was maintained with limited resistance for decades."

"The failings of this era very much reflect what young people are now saying about police shootings," EJI Director Bryan Stevenson told the Guardian, connecting the widespread acceptance of lynchings historically with the current racial justice movement. "It is about embracing this idea that 'black lives matter.'"

Stevenson continued: "I also think that the lynching era created a narrative of racial difference, a presumption of guilt, a presumption of dangerousness that got assigned to African Americans in particular--and that's the same presumption of guilt that burdens young kids living in urban areas who are sometimes menaced, threatened, or shot and killed by law enforcement officers."

The report documents a number of cases where black individuals were tortured and murdered, often in front of spectators, for such "crimes" as bumping into a white person, wearing their military uniforms after World War I, or not using the appropriate title when addressing a white person.

The report further suggests that the decline of lynching was tied to the rise of capital punishment--"a more palatable form of violence."

Capital punishment, the authors say, remains "rooted in racial terror" and is a "direct descendant of lynching."

Between 1910 and 1950, African Americans fell to just 22 percent of the South's population but constituted 75 percent of those executed there during that time. And today, African Americans compromise less than 13 percent of the nation's population but nearly 42 percent of those currently on death row in America.

The report continues: "Modern death sentences are disproportionately meted out to African Americans accused of crimes against white victims; efforts to combat racial bias and create federal protection against racial bias in the administration of the death penalty remain thwarted by familiar appeals to the rhetoric of states' rights; and regional data demonstrates that the modern death penalty in America mirrors racial violence of the past."

The authors hope that by confronting the reality of the country's racial history, Americans can work toward addressing the contemporary problems that are lynching's legacy.

"We cannot heal the deep wounds inflicted during the era of racial terrorism until we tell the truth about it," Stevenson said.