SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

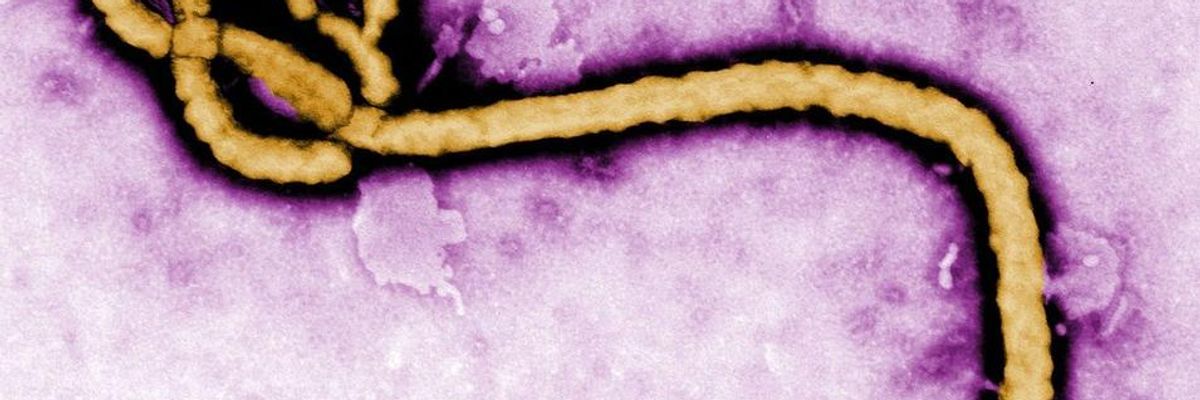

The Ebola virus under a microscope. It may not come in the form of a global pandemic, but outbreaks of viruses like West Nile, Dengue Fever, and Ebola are signaling that global warming is already having dramatic impacts in the development and spread of such diseases, according to zoological researchers Daniel Brooks and Eric Hoberg. (Photo: Frederick A. Murphy / CDC handout via EPA file)

An overall hotter planet and a rapidly-changing climate are altering the range of pathogens and increasing the appearance of infectious diseases, warns a new research paper published this week.

It may not come in the form of a global pandemic, but outbreaks of viruses like West Nile, and Ebola are signaling that global warming is already having dramatic impacts in the development and spread of such diseases, according to zoological researchers Daniel Brooks and Eric Hoberg. Increasing the level of concern is the impact rising temperatures may have on the emergence of previously unknown pathogens introduced to new regions or human environs.

"It's not that there's going to be one 'Andromeda Strain' that will wipe everybody out on the planet," explained Brooks, making reference to the 1971 science fiction novel by Michael Crichton. "There are going to be a lot of localized outbreaks putting pressure on medical and veterinary health systems. It will be the death of a thousand cuts."

In the study, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B on Monday, Brooks and Hoberg, who work for the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the U.S. National Parasite Collection respectively, warn that rising global temperatures have upended the balance of biodiversity of ecosystems which in turn threaten both human and animal populations across the planet.

While Brooks' research has focused on how parasites and pathogens operate in tropical regions, Hoberg has performed similar studies in the Arctic. "Over the last 30 years, the places we've been working have been heavily impacted by climate change," Brooks said in a recent interview. "Even though I was in the tropics and he was in the Arctic, we could see something was happening."

According to Science World Report:

In both of these regions, the scientists witnessed the arrival of species that hadn't previously lived in the area and the departure of others. This means that as animals change locations, they're exposed to new parasites and pathogens.

For example, after humans hunted capuchin and spider monkeys out of existence in some regions of Costa Rica, their parasites switched to howler monkeys. In addition, lungworms have moved northward and have shifted hosts from caribou to muskoxen in the Canadian Arctic.

What their research claims to show is that theses parasites, many of which carry the most dangerous pathogens, are much more capable of switching hosts than previously thought.

"Even though a parasite might have a very specialized relationship with one particular host in one particular place, there are other hosts that may be as susceptible," said Brooks. "West Nile Virus is a good example - no longer an acute problem for humans or wildlife in North America, it nonetheless is here to stay."

According to the abstract of the research paper, "Episodic shifts in climate and environmental settings, in conjunction with ecological mechanisms and host switching, are often critical determinants of parasite diversification, a view counter to more than a century of coevolutionary thinking about the nature of complex host-parasite assemblages."

Offering a warning that more must be done to recognize and combat the threat, Brooks stated, "We have to admit we're not winning the war against emerging diseases. We're not anticipating them. We're not paying attention to their basic biology, where they might come from and the potential for new pathogens to be introduced."

Common Dreams is powered by optimists who believe in the power of informed and engaged citizens to ignite and enact change to make the world a better place. We're hundreds of thousands strong, but every single supporter makes the difference. Your contribution supports this bold media model—free, independent, and dedicated to reporting the facts every day. Stand with us in the fight for economic equality, social justice, human rights, and a more sustainable future. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover the issues the corporate media never will. |

An overall hotter planet and a rapidly-changing climate are altering the range of pathogens and increasing the appearance of infectious diseases, warns a new research paper published this week.

It may not come in the form of a global pandemic, but outbreaks of viruses like West Nile, and Ebola are signaling that global warming is already having dramatic impacts in the development and spread of such diseases, according to zoological researchers Daniel Brooks and Eric Hoberg. Increasing the level of concern is the impact rising temperatures may have on the emergence of previously unknown pathogens introduced to new regions or human environs.

"It's not that there's going to be one 'Andromeda Strain' that will wipe everybody out on the planet," explained Brooks, making reference to the 1971 science fiction novel by Michael Crichton. "There are going to be a lot of localized outbreaks putting pressure on medical and veterinary health systems. It will be the death of a thousand cuts."

In the study, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B on Monday, Brooks and Hoberg, who work for the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the U.S. National Parasite Collection respectively, warn that rising global temperatures have upended the balance of biodiversity of ecosystems which in turn threaten both human and animal populations across the planet.

While Brooks' research has focused on how parasites and pathogens operate in tropical regions, Hoberg has performed similar studies in the Arctic. "Over the last 30 years, the places we've been working have been heavily impacted by climate change," Brooks said in a recent interview. "Even though I was in the tropics and he was in the Arctic, we could see something was happening."

According to Science World Report:

In both of these regions, the scientists witnessed the arrival of species that hadn't previously lived in the area and the departure of others. This means that as animals change locations, they're exposed to new parasites and pathogens.

For example, after humans hunted capuchin and spider monkeys out of existence in some regions of Costa Rica, their parasites switched to howler monkeys. In addition, lungworms have moved northward and have shifted hosts from caribou to muskoxen in the Canadian Arctic.

What their research claims to show is that theses parasites, many of which carry the most dangerous pathogens, are much more capable of switching hosts than previously thought.

"Even though a parasite might have a very specialized relationship with one particular host in one particular place, there are other hosts that may be as susceptible," said Brooks. "West Nile Virus is a good example - no longer an acute problem for humans or wildlife in North America, it nonetheless is here to stay."

According to the abstract of the research paper, "Episodic shifts in climate and environmental settings, in conjunction with ecological mechanisms and host switching, are often critical determinants of parasite diversification, a view counter to more than a century of coevolutionary thinking about the nature of complex host-parasite assemblages."

Offering a warning that more must be done to recognize and combat the threat, Brooks stated, "We have to admit we're not winning the war against emerging diseases. We're not anticipating them. We're not paying attention to their basic biology, where they might come from and the potential for new pathogens to be introduced."

An overall hotter planet and a rapidly-changing climate are altering the range of pathogens and increasing the appearance of infectious diseases, warns a new research paper published this week.

It may not come in the form of a global pandemic, but outbreaks of viruses like West Nile, and Ebola are signaling that global warming is already having dramatic impacts in the development and spread of such diseases, according to zoological researchers Daniel Brooks and Eric Hoberg. Increasing the level of concern is the impact rising temperatures may have on the emergence of previously unknown pathogens introduced to new regions or human environs.

"It's not that there's going to be one 'Andromeda Strain' that will wipe everybody out on the planet," explained Brooks, making reference to the 1971 science fiction novel by Michael Crichton. "There are going to be a lot of localized outbreaks putting pressure on medical and veterinary health systems. It will be the death of a thousand cuts."

In the study, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B on Monday, Brooks and Hoberg, who work for the Harold W. Manter Laboratory of Parasitology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and the U.S. National Parasite Collection respectively, warn that rising global temperatures have upended the balance of biodiversity of ecosystems which in turn threaten both human and animal populations across the planet.

While Brooks' research has focused on how parasites and pathogens operate in tropical regions, Hoberg has performed similar studies in the Arctic. "Over the last 30 years, the places we've been working have been heavily impacted by climate change," Brooks said in a recent interview. "Even though I was in the tropics and he was in the Arctic, we could see something was happening."

According to Science World Report:

In both of these regions, the scientists witnessed the arrival of species that hadn't previously lived in the area and the departure of others. This means that as animals change locations, they're exposed to new parasites and pathogens.

For example, after humans hunted capuchin and spider monkeys out of existence in some regions of Costa Rica, their parasites switched to howler monkeys. In addition, lungworms have moved northward and have shifted hosts from caribou to muskoxen in the Canadian Arctic.

What their research claims to show is that theses parasites, many of which carry the most dangerous pathogens, are much more capable of switching hosts than previously thought.

"Even though a parasite might have a very specialized relationship with one particular host in one particular place, there are other hosts that may be as susceptible," said Brooks. "West Nile Virus is a good example - no longer an acute problem for humans or wildlife in North America, it nonetheless is here to stay."

According to the abstract of the research paper, "Episodic shifts in climate and environmental settings, in conjunction with ecological mechanisms and host switching, are often critical determinants of parasite diversification, a view counter to more than a century of coevolutionary thinking about the nature of complex host-parasite assemblages."

Offering a warning that more must be done to recognize and combat the threat, Brooks stated, "We have to admit we're not winning the war against emerging diseases. We're not anticipating them. We're not paying attention to their basic biology, where they might come from and the potential for new pathogens to be introduced."