SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

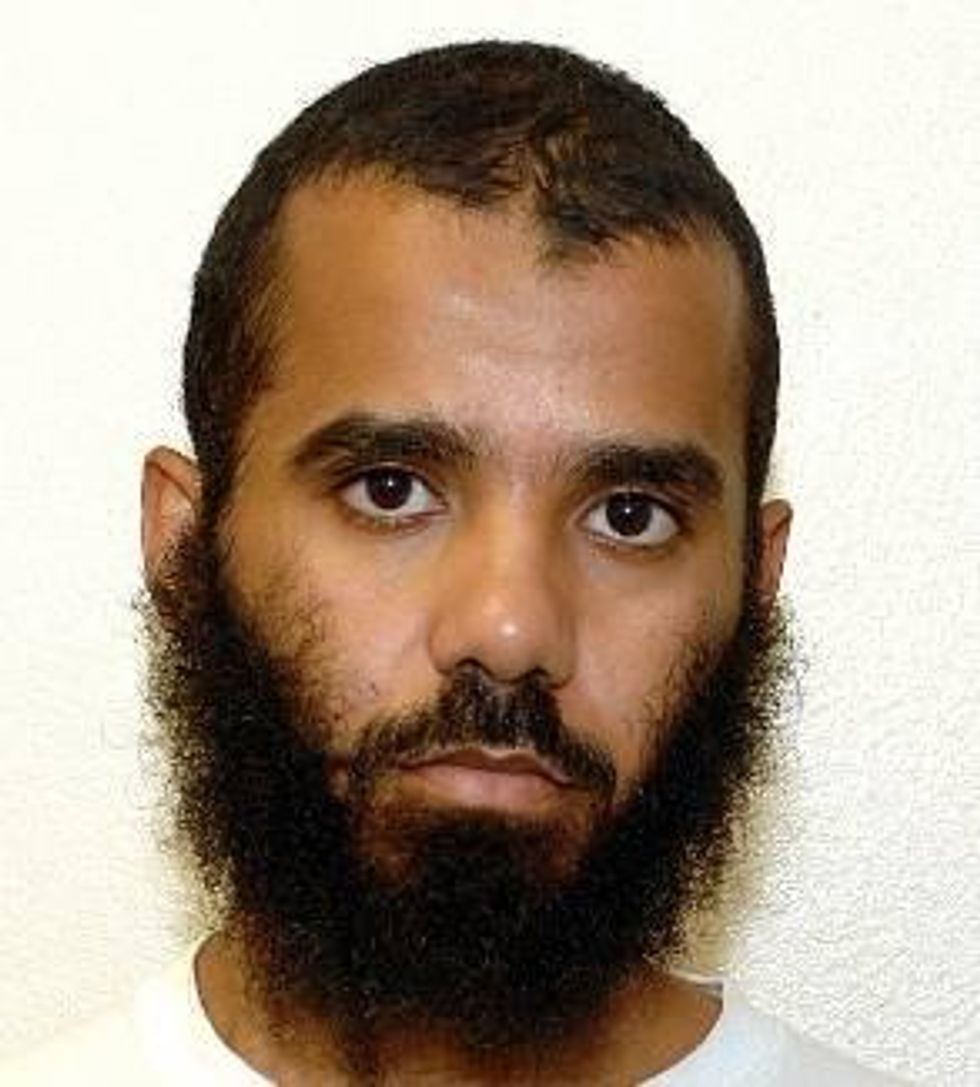

In a strikingly personal piece, Moath al-Alwi expresses his grief, anger, and frustrations after nearly 13 years of being held with no charges by the U.S. government. "I wonder now," he writes, "if the US follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?"

Moath al-Alwi, who has been a prisoner of the U.S. government and detained at the offshore prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba since 2002 without ever being charged with a crime or afforded a trial, has a simple yet urgent question for the American people and the U.S. government: Why am I still here?

"The world may turn a blind eye and find this number small. But for each of us here, the cost of our indefinite and unfair imprisonment is beyond immeasurable. Our families have lost fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons to this hell on earth. Many of us have unnecessarily lost over a decade of our already short time in this world, yearning to be free again."

--Moath al-Alwi

If the war in Afghanistan is now over, as he has heard President Obama and other lawmakers say many times, the Yemeni national wonders what possible reason could the U.S. have in keeping a man like himself--guilty of no crime--locked away on an island prison for nearly thirteen years.

Despite the protests of dedicated human rights and legal activists in the U.S. and around the world, the fact that the U.S. government continues to justify the "indefinite detention" of human beings for a war that has become detached from geographical boundaries and has no end date, remains one of the most glaring, yet ignored, realities of post-9/11 America.

In a strikingly personal piece that has now appeared in both Al-Jazeera English and The Nation, al-Alwi expresses his grief, anger, and frustrations. "I wonder now," he writes, "if the U.S. follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?"

Un-edited and in full, his missive to those who hold him captive follows:

I hear the war in Afghanistan is over.

This war was supposedly the reason I remained trapped, rotting in this endless horror at Guantanamo Bay. I write this letter today to ask, if this war has ended, why am I still here? Why has nothing changed?

Amid falling bombs and mass hysteria, I fled Afghanistan for safety when the US launched its military operations in 2001. I was abducted despite never fighting against the United States, was sold into US military custody, and then imprisoned, tortured, and abused at Guantanamo since 2002 without ever being charged with a single crime.

I protest this injustice by hunger striking, refusing food and sometimes water.One of Guantanamo's long-term hunger strikers, I am a frail man now, weighing only 96 pounds (44kg) at 5'5" (1.68m).

Recently, my latest strike surpassed its second year. My health is deteriorating rapidly, but my intention to continue my strike is steadfast. I do not want to kill myself. My religion prohibits suicide. But despite daily bouts of violent vomiting and sharp pain, I will not eat or drink to peacefully protest against the injustice of this place. My protest is the one form of control I have of my own life and I vow to continue it until I am free.

I remain on lockdown alone in my cell 22 hours a day. Despite my condition, prison authorities unleash an entire riot squad of six giant guards to forcibly extract me from my cell, restrain me onto a chair and brutally force-feed me daily. They push a thick tube down my nose until I bleed, after which I vomit.

This gruesome procedure may not be written about so much any more, but it remains my everyday reality. It is painful. And it is bewildering. How can I possibly resist anyone, let alone these men? Hunger striking is a form of peaceful and civil disobedience. It is not a crime. So why am I being punished? Why not humanely tube-feed me instead?

My time here has been ridden with unanswered questions. Two years ago, as I attempted to pray, a sudden raid was ordered and a guard deliberately shot me without warning or provocation. Once again, I was not resisting. So why did he shoot? My clothes, torn, were soaked in my own blood. I want the government to ask the guard who shot me to account for his actions.

I began to wonder if shooting without any provocation is legal in the US. But now I realise that US police officers get away with ruthlessly killing black people all the time.

I wonder now if the US follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?

For us at Guantanamo, this place is not fit for any living, breathing, human being. The US seems to want to smother us, to kill us slowly as we are left in a vacuum of uncertainty wondering if we will ever be free.

I have lived the past 13 years in this despair, at the cost of my dignity, paying the price for the US government's political theatre. Meanwhile, little has changed for the 122 men remaining at Guantanamo.

The world may turn a blind eye and find this number small. But for each of us here, the cost of our indefinite and unfair imprisonment is beyond immeasurable. Our families have lost fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons to this hell on earth. Many of us have unnecessarily lost over a decade of our already short time in this world, yearning to be free again.

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Moath al-Alwi, who has been a prisoner of the U.S. government and detained at the offshore prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba since 2002 without ever being charged with a crime or afforded a trial, has a simple yet urgent question for the American people and the U.S. government: Why am I still here?

"The world may turn a blind eye and find this number small. But for each of us here, the cost of our indefinite and unfair imprisonment is beyond immeasurable. Our families have lost fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons to this hell on earth. Many of us have unnecessarily lost over a decade of our already short time in this world, yearning to be free again."

--Moath al-Alwi

If the war in Afghanistan is now over, as he has heard President Obama and other lawmakers say many times, the Yemeni national wonders what possible reason could the U.S. have in keeping a man like himself--guilty of no crime--locked away on an island prison for nearly thirteen years.

Despite the protests of dedicated human rights and legal activists in the U.S. and around the world, the fact that the U.S. government continues to justify the "indefinite detention" of human beings for a war that has become detached from geographical boundaries and has no end date, remains one of the most glaring, yet ignored, realities of post-9/11 America.

In a strikingly personal piece that has now appeared in both Al-Jazeera English and The Nation, al-Alwi expresses his grief, anger, and frustrations. "I wonder now," he writes, "if the U.S. follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?"

Un-edited and in full, his missive to those who hold him captive follows:

I hear the war in Afghanistan is over.

This war was supposedly the reason I remained trapped, rotting in this endless horror at Guantanamo Bay. I write this letter today to ask, if this war has ended, why am I still here? Why has nothing changed?

Amid falling bombs and mass hysteria, I fled Afghanistan for safety when the US launched its military operations in 2001. I was abducted despite never fighting against the United States, was sold into US military custody, and then imprisoned, tortured, and abused at Guantanamo since 2002 without ever being charged with a single crime.

I protest this injustice by hunger striking, refusing food and sometimes water.One of Guantanamo's long-term hunger strikers, I am a frail man now, weighing only 96 pounds (44kg) at 5'5" (1.68m).

Recently, my latest strike surpassed its second year. My health is deteriorating rapidly, but my intention to continue my strike is steadfast. I do not want to kill myself. My religion prohibits suicide. But despite daily bouts of violent vomiting and sharp pain, I will not eat or drink to peacefully protest against the injustice of this place. My protest is the one form of control I have of my own life and I vow to continue it until I am free.

I remain on lockdown alone in my cell 22 hours a day. Despite my condition, prison authorities unleash an entire riot squad of six giant guards to forcibly extract me from my cell, restrain me onto a chair and brutally force-feed me daily. They push a thick tube down my nose until I bleed, after which I vomit.

This gruesome procedure may not be written about so much any more, but it remains my everyday reality. It is painful. And it is bewildering. How can I possibly resist anyone, let alone these men? Hunger striking is a form of peaceful and civil disobedience. It is not a crime. So why am I being punished? Why not humanely tube-feed me instead?

My time here has been ridden with unanswered questions. Two years ago, as I attempted to pray, a sudden raid was ordered and a guard deliberately shot me without warning or provocation. Once again, I was not resisting. So why did he shoot? My clothes, torn, were soaked in my own blood. I want the government to ask the guard who shot me to account for his actions.

I began to wonder if shooting without any provocation is legal in the US. But now I realise that US police officers get away with ruthlessly killing black people all the time.

I wonder now if the US follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?

For us at Guantanamo, this place is not fit for any living, breathing, human being. The US seems to want to smother us, to kill us slowly as we are left in a vacuum of uncertainty wondering if we will ever be free.

I have lived the past 13 years in this despair, at the cost of my dignity, paying the price for the US government's political theatre. Meanwhile, little has changed for the 122 men remaining at Guantanamo.

The world may turn a blind eye and find this number small. But for each of us here, the cost of our indefinite and unfair imprisonment is beyond immeasurable. Our families have lost fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons to this hell on earth. Many of us have unnecessarily lost over a decade of our already short time in this world, yearning to be free again.

Moath al-Alwi, who has been a prisoner of the U.S. government and detained at the offshore prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba since 2002 without ever being charged with a crime or afforded a trial, has a simple yet urgent question for the American people and the U.S. government: Why am I still here?

"The world may turn a blind eye and find this number small. But for each of us here, the cost of our indefinite and unfair imprisonment is beyond immeasurable. Our families have lost fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons to this hell on earth. Many of us have unnecessarily lost over a decade of our already short time in this world, yearning to be free again."

--Moath al-Alwi

If the war in Afghanistan is now over, as he has heard President Obama and other lawmakers say many times, the Yemeni national wonders what possible reason could the U.S. have in keeping a man like himself--guilty of no crime--locked away on an island prison for nearly thirteen years.

Despite the protests of dedicated human rights and legal activists in the U.S. and around the world, the fact that the U.S. government continues to justify the "indefinite detention" of human beings for a war that has become detached from geographical boundaries and has no end date, remains one of the most glaring, yet ignored, realities of post-9/11 America.

In a strikingly personal piece that has now appeared in both Al-Jazeera English and The Nation, al-Alwi expresses his grief, anger, and frustrations. "I wonder now," he writes, "if the U.S. follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?"

Un-edited and in full, his missive to those who hold him captive follows:

I hear the war in Afghanistan is over.

This war was supposedly the reason I remained trapped, rotting in this endless horror at Guantanamo Bay. I write this letter today to ask, if this war has ended, why am I still here? Why has nothing changed?

Amid falling bombs and mass hysteria, I fled Afghanistan for safety when the US launched its military operations in 2001. I was abducted despite never fighting against the United States, was sold into US military custody, and then imprisoned, tortured, and abused at Guantanamo since 2002 without ever being charged with a single crime.

I protest this injustice by hunger striking, refusing food and sometimes water.One of Guantanamo's long-term hunger strikers, I am a frail man now, weighing only 96 pounds (44kg) at 5'5" (1.68m).

Recently, my latest strike surpassed its second year. My health is deteriorating rapidly, but my intention to continue my strike is steadfast. I do not want to kill myself. My religion prohibits suicide. But despite daily bouts of violent vomiting and sharp pain, I will not eat or drink to peacefully protest against the injustice of this place. My protest is the one form of control I have of my own life and I vow to continue it until I am free.

I remain on lockdown alone in my cell 22 hours a day. Despite my condition, prison authorities unleash an entire riot squad of six giant guards to forcibly extract me from my cell, restrain me onto a chair and brutally force-feed me daily. They push a thick tube down my nose until I bleed, after which I vomit.

This gruesome procedure may not be written about so much any more, but it remains my everyday reality. It is painful. And it is bewildering. How can I possibly resist anyone, let alone these men? Hunger striking is a form of peaceful and civil disobedience. It is not a crime. So why am I being punished? Why not humanely tube-feed me instead?

My time here has been ridden with unanswered questions. Two years ago, as I attempted to pray, a sudden raid was ordered and a guard deliberately shot me without warning or provocation. Once again, I was not resisting. So why did he shoot? My clothes, torn, were soaked in my own blood. I want the government to ask the guard who shot me to account for his actions.

I began to wonder if shooting without any provocation is legal in the US. But now I realise that US police officers get away with ruthlessly killing black people all the time.

I wonder now if the US follows any rule of law at all: the Geneva Conventions or even its own Constitution. Where is the freedom and justice for all that it so proudly boasts to the world?

For us at Guantanamo, this place is not fit for any living, breathing, human being. The US seems to want to smother us, to kill us slowly as we are left in a vacuum of uncertainty wondering if we will ever be free.

I have lived the past 13 years in this despair, at the cost of my dignity, paying the price for the US government's political theatre. Meanwhile, little has changed for the 122 men remaining at Guantanamo.

The world may turn a blind eye and find this number small. But for each of us here, the cost of our indefinite and unfair imprisonment is beyond immeasurable. Our families have lost fathers, brothers, husbands, and sons to this hell on earth. Many of us have unnecessarily lost over a decade of our already short time in this world, yearning to be free again.