SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

"This culture of corruption and unethical, uncaring behavior predated Flint by at least [eight] years," said lead expert Marc Edwards. (Photo: Joyce Zhu/FlintWaterStudy.org)

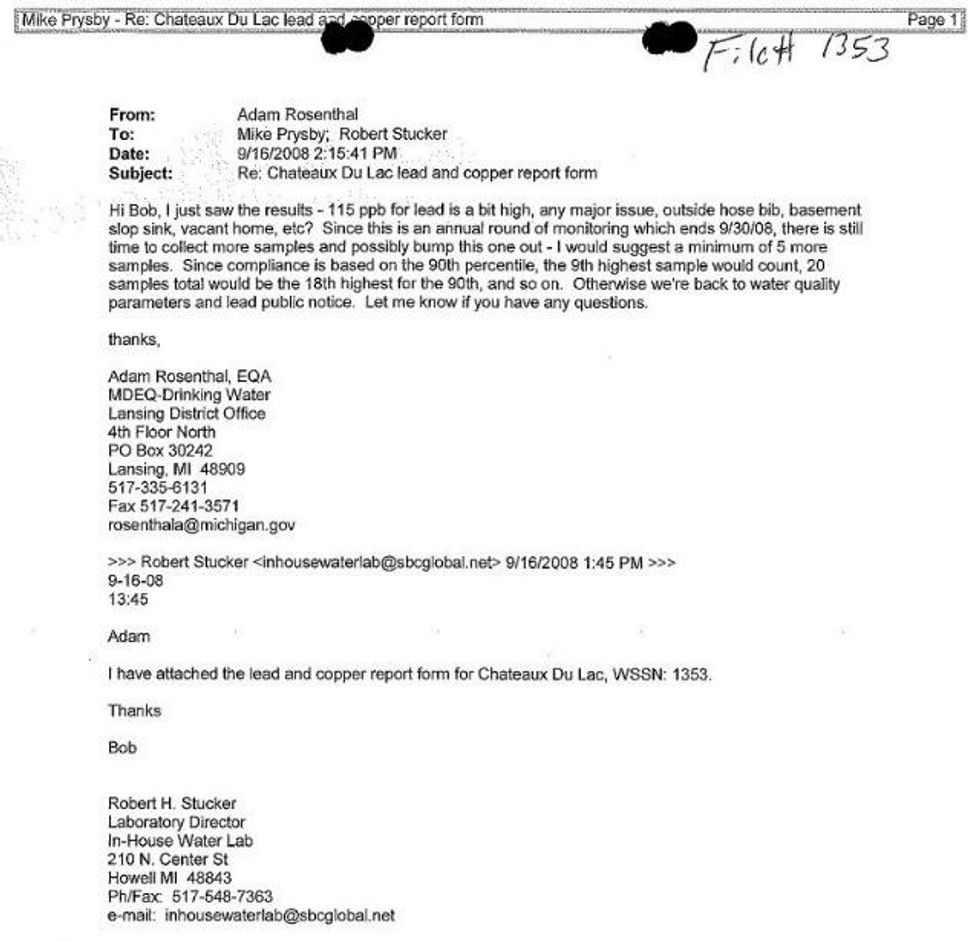

A newly resurfaced email demonstrates that in 2008 an official from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) tried to game lead tests by suggesting that technicians collect extra water samples to make the average lead count for a community appear artificially low.

The email was sent in response to a test result that showed one home's lead levels were ten times the federal action level of 15 parts per billion, and urged the lead test technician to take an additional set of water samples to "bump out" the high result so that the MDEQ wouldn't be required to notify the community of the high levels of lead in its water.

"Otherwise we're back to water quality parameters and lead public notice," complained Adam Rosenthal of the MDEQ's Drinking Water office in the email.

"Oh my gosh, I've never heard [it] more black and white," said Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech professor and lead expert who helped uncover the crisis, to the Guardian. "In the Flint emails, if you recall, it was a little bit implied ... this is like telling the strategy, which is: 'you failed, but if you go out and get a whole bunch more samples that are low, then you can game it lower.'"

"[This email] just shows that this culture of corruption and unethical, uncaring behavior predated Flint by at least [eight] years," as Edwards told the Guardian.

The revelation comes less than a week after criminal charges were filed against three MDEQ employees for their role in Flint's water crisis. Rosenthal was not one of those officials charged.

Two MDEQ officials, Mike Prysby and Stephen Busch, were copied on Rosenthal's 2008 email and last week both were charged with "misconduct in office, conspiracy to tamper with evidence, tampering with evidence, a treatment violation of the Michigan Safe Drinking Water Act and a monitoring violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act" in relation to the Flint water crisis, as MLive reported.

The 2008 lead tests were taken at the Chateaux Du Lac Condominiums, a homeowners assocation in Fenton, Michigan, that operates on a private water system and has struggled periodically with high lead levels. The association's water system "has exceeded federal lead action levels, set to trigger remediation efforts such as public education campaigns or expensive corrosion control, eight times over the past 20 years," the Guardian writes.

"In early September 2008, a water laboratory technician collected samples from five of the nearly 45 homes in the association, the minimally required amount," the newspaper reports.

"The technician submitted the samples to the Michigan department of environmental quality for review. Of the five samples, one home registered a lead level of 115 parts per billion (ppb), nearly 10 times higher than the federal action level of 15ppb--and thereby put the Chateaux's water system out of compliance," the Guardian points out. "If at least 90% of homes tested for lead register a level at or below 15ppb, the system is deemed in compliance with federal regulation."

In his email, Rosenthal recommended the technician collect "a minimum of 5 more samples"--if those five extra samples measured below the federal action level, the system would have been in compliance and the government would not have been required to notify homeowners of the high lead test result.

"Chateaux still had to publish a public lead notice in 2008," the Guardian notes, "and documentation shows that only five tests were performed, including the high test discussed in the email exchange."

And so it appears the technician was not swayed by Rosenthal's urging to manipulate lead test results in 2008, but critics charge that the habit of ignoring the public good in favor of bureaucratic convenience continued among Michigan government officials and directly contributed to the Flint disaster.

It was also announced on Wednesday that President Obama will be visiting Flint on May 4 to speak directly with residents about the crisis and to receive an in-person briefing about the federal government's efforts to help.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

A newly resurfaced email demonstrates that in 2008 an official from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) tried to game lead tests by suggesting that technicians collect extra water samples to make the average lead count for a community appear artificially low.

The email was sent in response to a test result that showed one home's lead levels were ten times the federal action level of 15 parts per billion, and urged the lead test technician to take an additional set of water samples to "bump out" the high result so that the MDEQ wouldn't be required to notify the community of the high levels of lead in its water.

"Otherwise we're back to water quality parameters and lead public notice," complained Adam Rosenthal of the MDEQ's Drinking Water office in the email.

"Oh my gosh, I've never heard [it] more black and white," said Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech professor and lead expert who helped uncover the crisis, to the Guardian. "In the Flint emails, if you recall, it was a little bit implied ... this is like telling the strategy, which is: 'you failed, but if you go out and get a whole bunch more samples that are low, then you can game it lower.'"

"[This email] just shows that this culture of corruption and unethical, uncaring behavior predated Flint by at least [eight] years," as Edwards told the Guardian.

The revelation comes less than a week after criminal charges were filed against three MDEQ employees for their role in Flint's water crisis. Rosenthal was not one of those officials charged.

Two MDEQ officials, Mike Prysby and Stephen Busch, were copied on Rosenthal's 2008 email and last week both were charged with "misconduct in office, conspiracy to tamper with evidence, tampering with evidence, a treatment violation of the Michigan Safe Drinking Water Act and a monitoring violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act" in relation to the Flint water crisis, as MLive reported.

The 2008 lead tests were taken at the Chateaux Du Lac Condominiums, a homeowners assocation in Fenton, Michigan, that operates on a private water system and has struggled periodically with high lead levels. The association's water system "has exceeded federal lead action levels, set to trigger remediation efforts such as public education campaigns or expensive corrosion control, eight times over the past 20 years," the Guardian writes.

"In early September 2008, a water laboratory technician collected samples from five of the nearly 45 homes in the association, the minimally required amount," the newspaper reports.

"The technician submitted the samples to the Michigan department of environmental quality for review. Of the five samples, one home registered a lead level of 115 parts per billion (ppb), nearly 10 times higher than the federal action level of 15ppb--and thereby put the Chateaux's water system out of compliance," the Guardian points out. "If at least 90% of homes tested for lead register a level at or below 15ppb, the system is deemed in compliance with federal regulation."

In his email, Rosenthal recommended the technician collect "a minimum of 5 more samples"--if those five extra samples measured below the federal action level, the system would have been in compliance and the government would not have been required to notify homeowners of the high lead test result.

"Chateaux still had to publish a public lead notice in 2008," the Guardian notes, "and documentation shows that only five tests were performed, including the high test discussed in the email exchange."

And so it appears the technician was not swayed by Rosenthal's urging to manipulate lead test results in 2008, but critics charge that the habit of ignoring the public good in favor of bureaucratic convenience continued among Michigan government officials and directly contributed to the Flint disaster.

It was also announced on Wednesday that President Obama will be visiting Flint on May 4 to speak directly with residents about the crisis and to receive an in-person briefing about the federal government's efforts to help.

A newly resurfaced email demonstrates that in 2008 an official from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) tried to game lead tests by suggesting that technicians collect extra water samples to make the average lead count for a community appear artificially low.

The email was sent in response to a test result that showed one home's lead levels were ten times the federal action level of 15 parts per billion, and urged the lead test technician to take an additional set of water samples to "bump out" the high result so that the MDEQ wouldn't be required to notify the community of the high levels of lead in its water.

"Otherwise we're back to water quality parameters and lead public notice," complained Adam Rosenthal of the MDEQ's Drinking Water office in the email.

"Oh my gosh, I've never heard [it] more black and white," said Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech professor and lead expert who helped uncover the crisis, to the Guardian. "In the Flint emails, if you recall, it was a little bit implied ... this is like telling the strategy, which is: 'you failed, but if you go out and get a whole bunch more samples that are low, then you can game it lower.'"

"[This email] just shows that this culture of corruption and unethical, uncaring behavior predated Flint by at least [eight] years," as Edwards told the Guardian.

The revelation comes less than a week after criminal charges were filed against three MDEQ employees for their role in Flint's water crisis. Rosenthal was not one of those officials charged.

Two MDEQ officials, Mike Prysby and Stephen Busch, were copied on Rosenthal's 2008 email and last week both were charged with "misconduct in office, conspiracy to tamper with evidence, tampering with evidence, a treatment violation of the Michigan Safe Drinking Water Act and a monitoring violation of the Safe Drinking Water Act" in relation to the Flint water crisis, as MLive reported.

The 2008 lead tests were taken at the Chateaux Du Lac Condominiums, a homeowners assocation in Fenton, Michigan, that operates on a private water system and has struggled periodically with high lead levels. The association's water system "has exceeded federal lead action levels, set to trigger remediation efforts such as public education campaigns or expensive corrosion control, eight times over the past 20 years," the Guardian writes.

"In early September 2008, a water laboratory technician collected samples from five of the nearly 45 homes in the association, the minimally required amount," the newspaper reports.

"The technician submitted the samples to the Michigan department of environmental quality for review. Of the five samples, one home registered a lead level of 115 parts per billion (ppb), nearly 10 times higher than the federal action level of 15ppb--and thereby put the Chateaux's water system out of compliance," the Guardian points out. "If at least 90% of homes tested for lead register a level at or below 15ppb, the system is deemed in compliance with federal regulation."

In his email, Rosenthal recommended the technician collect "a minimum of 5 more samples"--if those five extra samples measured below the federal action level, the system would have been in compliance and the government would not have been required to notify homeowners of the high lead test result.

"Chateaux still had to publish a public lead notice in 2008," the Guardian notes, "and documentation shows that only five tests were performed, including the high test discussed in the email exchange."

And so it appears the technician was not swayed by Rosenthal's urging to manipulate lead test results in 2008, but critics charge that the habit of ignoring the public good in favor of bureaucratic convenience continued among Michigan government officials and directly contributed to the Flint disaster.

It was also announced on Wednesday that President Obama will be visiting Flint on May 4 to speak directly with residents about the crisis and to receive an in-person briefing about the federal government's efforts to help.