A massive swath of hot water off the West Coast of North America devastated marine life for years--killing sea lions, whales, starfish, birds, and more--and new research finds that such marine heatwaves are growing more and more frequent.

Michael Slezak in the Guardian and Craig Welch in National Geographic this weekend both published in-depth explorations of the unprecedented phenomenon.

It is indeed a new problem, a result of a rapidly warming climate: a marine heatwave had never been formally recorded until the past few years and the term wasn't even coined until 2011, Slezak reported.

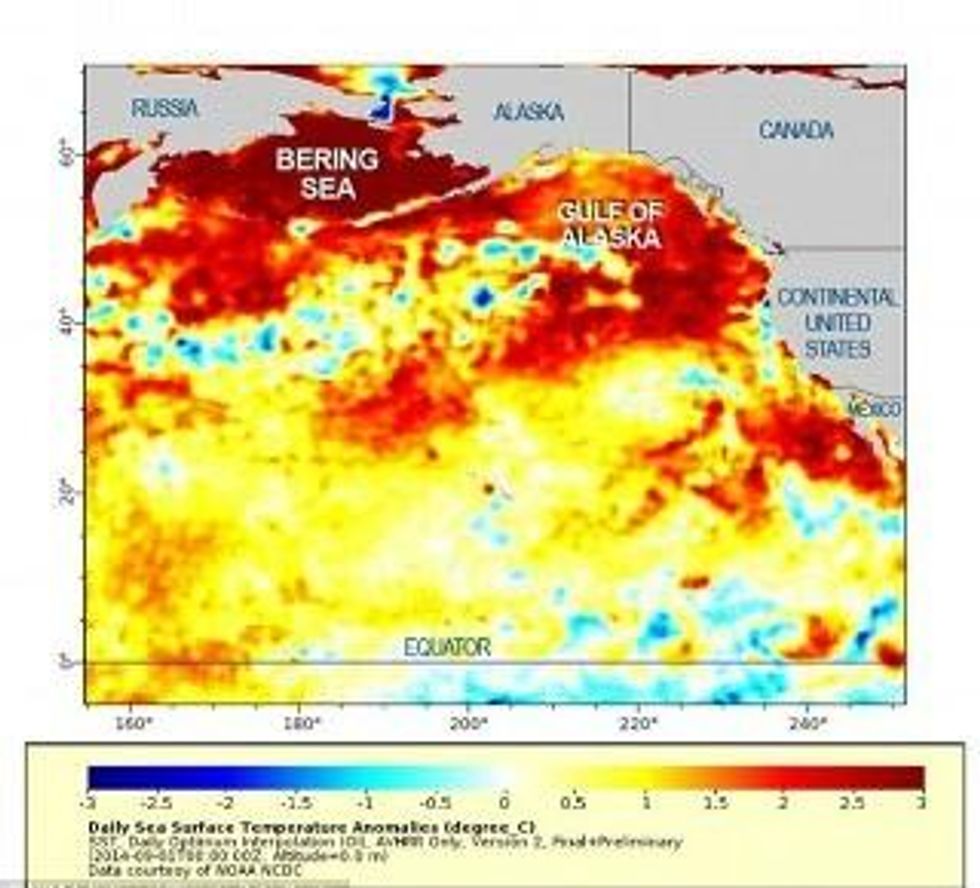

Welch described the havoc wreaked thus far by what climatologists termed "the blob," a hot spot off the North American Pacific coast that began in 2013:

In the past few years death had become a bigger part of life in the ocean off North America's West Coast. Millions of sea stars melted away in tide pools from Santa Barbara, California, to Sitka, Alaska, their bodies dissolving, their arms breaking free and wandering off. Hundreds of thousands of ocean-feeding seabirds tumbled dead onto beaches. Twenty times more sea lions than average starved in California. I watched scientists lift sea otter carcasses onto orange sleds as they perished in Homer--79 turned up dead there in one month. By year's end, whale deaths in the western Gulf of Alaska would hit a staggering 45. Mass fatalities can be as elemental in nature as wildfire in a lodgepole pine forest, whipping through quickly, killing off the weak and clearing the way for rebirth. But these mysterious casualties all shared one thing: They overlapped with a period when West Coast ocean waters were blowing past modern temperature records.

Slezak put it more simply: "Plague, famine, pestilence, and death was sweeping the northern Pacific Ocean between 2014 and 2015."

And while the blob appeared on the brink of disappearing in early 2016--with some scientists even declaring it dead--new research showed that it never left, and that it continues to disrupt the marine ecosystem from Alaska to Mexico.

Three other such "blobs" were detected off the coast of Australia this year, Slezak noted, and the region's unprecedented rise in ocean temperatures spurred the death of most of the Great Barrier Reef, the wholesale killing of kelp forests that supported critical fisheries, and the worst mangrove die-off ever seen.

Global warming is the likely culprit, both Slezak and Welch noted. "Is long-term warming somehow the puppeteer controlling things in the background?" Nate Mantua of NOAA's Southwest Fisheries Science Center in Santa Cruz, California, asked Welch. "I haven't seen proof, but it's clearly a prime suspect."

Indeed, a new body of research is focusing on determining how much--not whether--global warming will contribute to the increasing prevalence of these deadly underwater heat waves: Slezak wrote that "the big question facing researchers is if they are increasing in frequency or severity or both, as a result of global warming."

Emanuele Di Lorenzo, an oceanographer at the Georgia Institute of Technology who conducted an in-depth study of "the blob," warned that warming ocean temperatures have a multiplying effect, as one extreme event catalyzes several others.

"Looking at what is happening," Slezak wrote, Di Lorenzo "thinks climate change is increasing both the frequency and severity of marine heatwaves." Slezak continues:

So much so, he wonders if climate models are wrong, and underestimating the fluctuations in temperature that will occur as the globe warms.

"The real system--if you look at the observations, and this is a paper I will publish very soon--the increase in variance is much much stronger than what models are predicting," he says. "Maybe our models are too conservative."

Di Lorenzo says this sort of "variance"--including things like heatwaves--will always be stronger in the ocean, because the ocean has a kind of "memory" that means events build on top of each other, multiplying their effects.

That memory is a result of temperature changing much more slowly in the ocean, as well as the ocean being able to absorb more heat in general.

A climatologist recently confirmed that the frequency and duration of marine heatwaves is significantly increasing, Slezak wrote, and peer review and publication of that study is currently pending.

Di Lorenzo remarked to Slezak that "the increasing frequency of these events is well outside of what anyone predicted."

The mass deaths wrought by heatwaves such as the North American "blob" are likely a harbinger of things to come, both Slezak and Welch observed. Indeed, "the blob offers something of an analogue for future seas under climate change," Welch noted. "And marine life in this sea of tomorrow will look very different."