New research about weakening ocean currents is raising concerns about extreme weather in Western Europe and sea level rise along North America's East Coast. (Photo: Thomas/Flickr/cc)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

New research about weakening ocean currents is raising concerns about extreme weather in Western Europe and sea level rise along North America's East Coast. (Photo: Thomas/Flickr/cc)

New research published Wednesday in the journal Nature raises alarm about how global warming is impacting the Atlantic Ocean's Gulf Stream System, and how weakening ocean currents could influence extreme weather in Western Europe and sea level rise along North America's East Coast.

Although the two studies draw different conclusions about timing and causation, researchers agree that the system of ocean currents called Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) has notably weakened in recent decades.

This key takeaway, as Damian Carrington at the Guardiannotes, throws into question "previous predictions that a catastrophic collapse of the Gulf Stream would take centuries to occur. Such a collapse would see western Europe suffer far more extreme winters, sea levels rise fast on the eastern seaboard of the U.S., and would disrupt vital tropical rains."

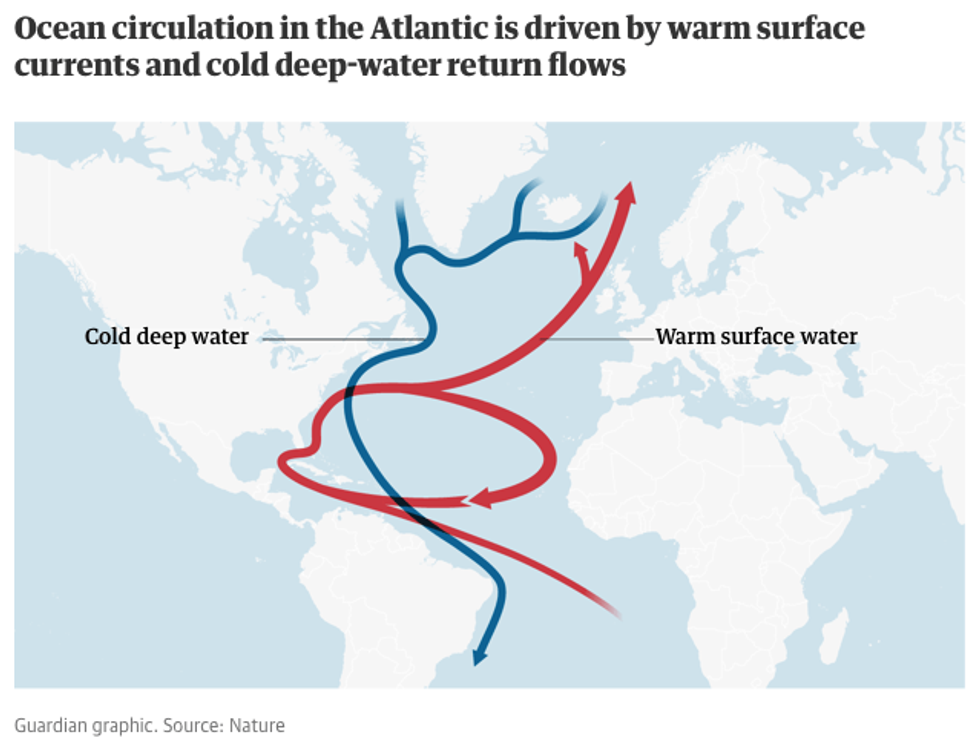

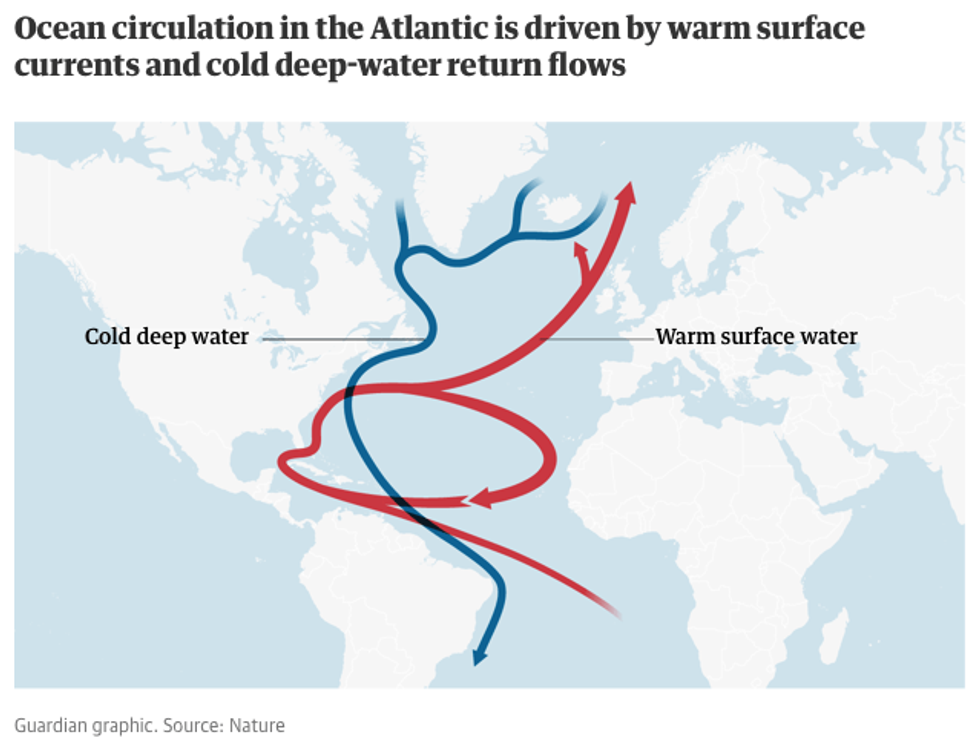

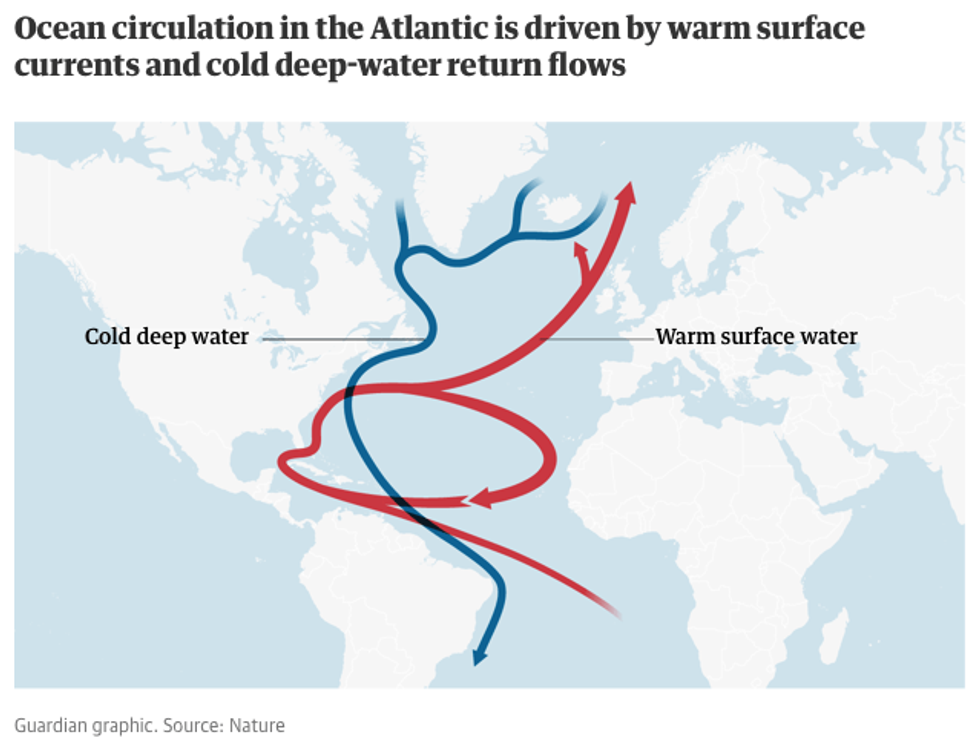

The AMOC system has been compared to a conveyer belt: Warm surface water flows northward, where it cools and then sinks due to its increased density. It then cycles back toward the equator at a deeper level along the North American continent, as shown in this chart:

One Naturestudy concluded that since the mid-20th century, AMOC has weakened by about 15 percent--or, as one of the authors put it, "around fifteen times the flow of the Amazon, and thus three times the outflow of all rivers on earth combined." These researchers concluded that the weakening was likely driven by anthropogenic climate change.

The second study--which relied on a different methodology--concluded that AMOC started weakening earlier, and likely due to natural causes at the end of the Little Ice Age, around 1850. However, the second study still found that circulation has been "anomalously weak over the past 150 years or so...compared with the preceding 1,500 years," and that it has continued to weaken in the recent era of global warming fueled by human activity.

Noting that more research is needed, and that "neither of the new studies is based on direct measurements of the circulation because we haven't had those for very long (a little over 10 years)," Washington Post environmental reporter Chris Mooney broke down the reports' key conclusions in a series of tweets:

In an editorial about the pair of papers, Nature also called for futher study, pointing out:

Importantly, the findings agree that the AMOC is in a relatively weak state. The wide margin of disagreement between the two independent studies on when the circulation started to weaken is probably due to the different methods used--and it highlights how immensely difficult it is to capture the AMOC's past variability. This will probably frustrate those who prefer their science to send a clear signal. But then, science is rarely so obliging. Can the effects of climate change and natural variability on the AMOC be disentangled? And if the ocean circulation is sensitive to climate change, as is highly likely, will the currents respond abruptly and perhaps violently at some point, or will the transition be smooth? These are among the most pressing questions in climate science.

"There is more to be done," the Nature editorial concludes. "Meticulous observation is a prerequisite for understanding the oceans on which, ultimately, humankind depends."

Common Dreams is powered by optimists who believe in the power of informed and engaged citizens to ignite and enact change to make the world a better place. We're hundreds of thousands strong, but every single supporter makes the difference. Your contribution supports this bold media model—free, independent, and dedicated to reporting the facts every day. Stand with us in the fight for economic equality, social justice, human rights, and a more sustainable future. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover the issues the corporate media never will. |

New research published Wednesday in the journal Nature raises alarm about how global warming is impacting the Atlantic Ocean's Gulf Stream System, and how weakening ocean currents could influence extreme weather in Western Europe and sea level rise along North America's East Coast.

Although the two studies draw different conclusions about timing and causation, researchers agree that the system of ocean currents called Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) has notably weakened in recent decades.

This key takeaway, as Damian Carrington at the Guardiannotes, throws into question "previous predictions that a catastrophic collapse of the Gulf Stream would take centuries to occur. Such a collapse would see western Europe suffer far more extreme winters, sea levels rise fast on the eastern seaboard of the U.S., and would disrupt vital tropical rains."

The AMOC system has been compared to a conveyer belt: Warm surface water flows northward, where it cools and then sinks due to its increased density. It then cycles back toward the equator at a deeper level along the North American continent, as shown in this chart:

One Naturestudy concluded that since the mid-20th century, AMOC has weakened by about 15 percent--or, as one of the authors put it, "around fifteen times the flow of the Amazon, and thus three times the outflow of all rivers on earth combined." These researchers concluded that the weakening was likely driven by anthropogenic climate change.

The second study--which relied on a different methodology--concluded that AMOC started weakening earlier, and likely due to natural causes at the end of the Little Ice Age, around 1850. However, the second study still found that circulation has been "anomalously weak over the past 150 years or so...compared with the preceding 1,500 years," and that it has continued to weaken in the recent era of global warming fueled by human activity.

Noting that more research is needed, and that "neither of the new studies is based on direct measurements of the circulation because we haven't had those for very long (a little over 10 years)," Washington Post environmental reporter Chris Mooney broke down the reports' key conclusions in a series of tweets:

In an editorial about the pair of papers, Nature also called for futher study, pointing out:

Importantly, the findings agree that the AMOC is in a relatively weak state. The wide margin of disagreement between the two independent studies on when the circulation started to weaken is probably due to the different methods used--and it highlights how immensely difficult it is to capture the AMOC's past variability. This will probably frustrate those who prefer their science to send a clear signal. But then, science is rarely so obliging. Can the effects of climate change and natural variability on the AMOC be disentangled? And if the ocean circulation is sensitive to climate change, as is highly likely, will the currents respond abruptly and perhaps violently at some point, or will the transition be smooth? These are among the most pressing questions in climate science.

"There is more to be done," the Nature editorial concludes. "Meticulous observation is a prerequisite for understanding the oceans on which, ultimately, humankind depends."

New research published Wednesday in the journal Nature raises alarm about how global warming is impacting the Atlantic Ocean's Gulf Stream System, and how weakening ocean currents could influence extreme weather in Western Europe and sea level rise along North America's East Coast.

Although the two studies draw different conclusions about timing and causation, researchers agree that the system of ocean currents called Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) has notably weakened in recent decades.

This key takeaway, as Damian Carrington at the Guardiannotes, throws into question "previous predictions that a catastrophic collapse of the Gulf Stream would take centuries to occur. Such a collapse would see western Europe suffer far more extreme winters, sea levels rise fast on the eastern seaboard of the U.S., and would disrupt vital tropical rains."

The AMOC system has been compared to a conveyer belt: Warm surface water flows northward, where it cools and then sinks due to its increased density. It then cycles back toward the equator at a deeper level along the North American continent, as shown in this chart:

One Naturestudy concluded that since the mid-20th century, AMOC has weakened by about 15 percent--or, as one of the authors put it, "around fifteen times the flow of the Amazon, and thus three times the outflow of all rivers on earth combined." These researchers concluded that the weakening was likely driven by anthropogenic climate change.

The second study--which relied on a different methodology--concluded that AMOC started weakening earlier, and likely due to natural causes at the end of the Little Ice Age, around 1850. However, the second study still found that circulation has been "anomalously weak over the past 150 years or so...compared with the preceding 1,500 years," and that it has continued to weaken in the recent era of global warming fueled by human activity.

Noting that more research is needed, and that "neither of the new studies is based on direct measurements of the circulation because we haven't had those for very long (a little over 10 years)," Washington Post environmental reporter Chris Mooney broke down the reports' key conclusions in a series of tweets:

In an editorial about the pair of papers, Nature also called for futher study, pointing out:

Importantly, the findings agree that the AMOC is in a relatively weak state. The wide margin of disagreement between the two independent studies on when the circulation started to weaken is probably due to the different methods used--and it highlights how immensely difficult it is to capture the AMOC's past variability. This will probably frustrate those who prefer their science to send a clear signal. But then, science is rarely so obliging. Can the effects of climate change and natural variability on the AMOC be disentangled? And if the ocean circulation is sensitive to climate change, as is highly likely, will the currents respond abruptly and perhaps violently at some point, or will the transition be smooth? These are among the most pressing questions in climate science.

"There is more to be done," the Nature editorial concludes. "Meticulous observation is a prerequisite for understanding the oceans on which, ultimately, humankind depends."