Twenty years ago, on Jan. 1, 1994, a trade deal championed by Democratic President Bill Clinton went into effect. The North American Free Trade Agreement was meant to integrate the economies of the United States, Canada and Mexico by breaking down trade barriers between them, creating jobs and closing the wage gap between the U.S. and Mexico.

What in fact happened under NAFTA was that heavily subsidized U.S. corn flooded the Mexican market, putting millions of farmers out of work. Multinational corporations opened up factories creating low-wage jobs at the expense of organized labor and the environment. This, in turn, drove waves of migration north.

Meanwhile, corporate profits soared, and Mexico boasted the richest man in the world, Carlos Slim. Walmart and Krispy Kreme conquered Mexico, and ordinary Mexicans had access to the same consumer goods as their neighbors to the north. The economies of all three nations, measured only by GDP rather than jobs or wages, were pronounced grand successes, even though the U.S. and Canada disproportionately reaped more financial benefits.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., manufacturing jobs fell dramatically and organized labor lost even more clout. The Great Recession of 2008 worsened the downward trend, especially for Mexicans. Mexico's economy, tied intimately to the U.S.' because of NAFTA, suffered more than any other country in Latin America.

News reports on NAFTA's anniversary point out that as a result of the free trade agreement, Mexicans today can buy designer sneakers or iPhones. Manuel Perez-Rocha, an associate fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies in Washington, D.C., and a Mexican national, told me in an interview, "This is a new spin--praising the riches of consumerism. All these new analyses about how Mexico is becoming a more middle-class society and able to buy more products from the United States--it's just baloney. According to official statistics from Mexico, most Mexicans are poor and belong to the lower class, and this is the reason why there has been so much migration to the United States."

Coinciding with NAFTA was one of the biggest waves of migration from Mexico to the U.S., which slowed only in recent years. Perez-Rocha asserted that, "The fact is that most Mexicans are jobless, or have very difficult job conditions, or are underemployed, and so the push for migration continues. Most of the routes by which people would migrate from Central America and Mexico to the United States have been severed by violence, and by the 'narcos' [drug lords], sometimes with the complicity of the Mexican migration authorities."

Even analysts who tout the economic benefits of NAFTA to all three member countries acknowledge that Mexico has benefited less than its neighbors to the north. Perez-Rocha confirmed that, saying, "During NAFTA, Mexico has had the slowest rate of economic growth than [with] any other previous economic strategy since the 1930s. From 1994 to 2013, Mexico's gross domestic product per capita has grown at a paltry rate of 0.89 percent per year." Additionally, "During NAFTA, Mexico's economy grew much slower than almost every Latin American country. So to say that NAFTA has benefited the Mexican economy is also a myth. It has boosted trade and investment, but this has not translated into meaningful growth that generates jobs. One of the problems that NAFTA has generated is basically an exporting economy for transnational corporations, not for the Mexican industry per se."

It turns out that not only did NAFTA, "flood Mexico with imported corn and cheap grains from the United States," but "it also destroyed Mexico's own industries," according to Perez-Rocha.

Having grown up in Mexico, the analyst reminisced, "Before NAFTA, I still remember how my father would take me to different industries in which Mexico would manufacture its own tractors and buses. We had an industry that was completely dismantled to give way to bigger corporations from the United States to use Mexico as an assembly plant for exporting cars back to the United States. And this hasn't produced the boom of jobs that was promised." Perez-Rocha concluded,"So in the end what NAFTA did was destroy the Mexican national industry and destroy a lot of jobs."

One of the promises of NAFTA was that it would reduce the wage gap between American and Mexican workers. In fact, Mexicans earn less than they did in 1994 when NAFTA was first enacted. Perez-Rocha concurred, saying, "This was one of the unfulfilled promises [of NAFTA]. The wage gap between the United States workers and Mexicans remained basically the same. And it is very notorious today that proponents of NAFTA are even saying that Mexico is a very attractive country for foreign investment and they cite precisely the low cost of labor." Nearly half of the Mexican population currently lives below the poverty line.

NAFTA went into effect on the same day that the Zapatista National Liberation Army in Chiapas, Mexico, made itself public. The Zapatistas, with incredible foresight, called NAFTA a "death sentence." According to Perez-Rocha, the Zapatistas "knew what is evident today--that the countryside of Mexico was going to be devastated. ... What we've seen in 20 years--and I'm very certain that the Zapatistas foresaw this--was the devastation of the Mexican countryside and of the livelihoods of farmers to give way to a narco-economy that has inundated Mexico. This has become very evident in the past few years."

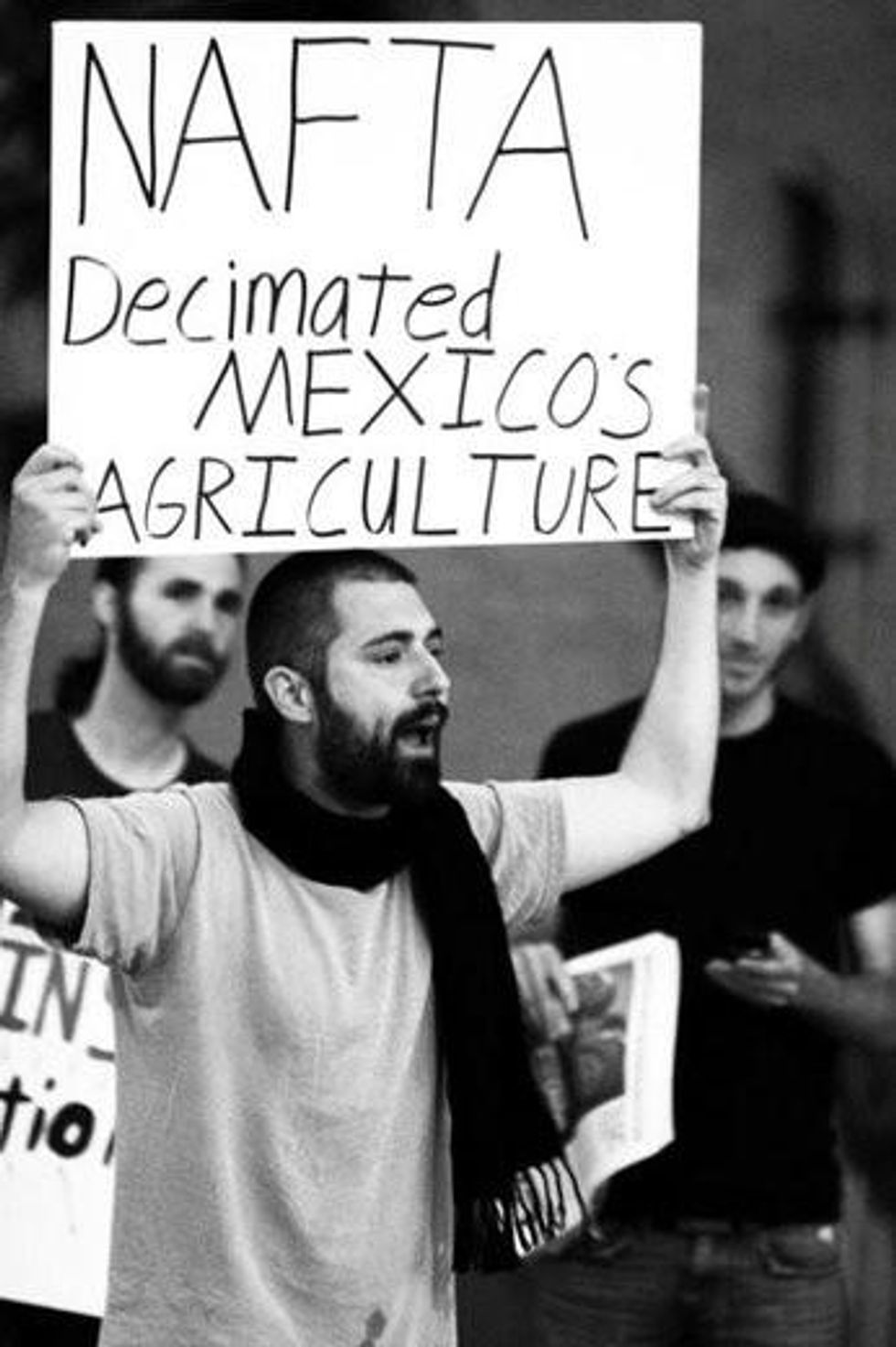

A protest on Jan. 1, 2014, on the border between Ciudad Juarez and El Paso, Texas, marked the 20th anniversary of the start of the Zapatista Uprising and of the launch of NAFTA. Perez-Rocha, who closely followed the action, cited photos in social media of activists carrying signs that read, "NAFTA has meant less farmers and more Narcos in the countryside."

Not only has NAFTA negatively affected Mexico's economy, jobs and wages, it has also devastated the air, water and land. Perez-Rocha has been researching the environmental impact of NAFTA and found that "there has been an increase in export-oriented agriculture that relies on fossil fuels, chemicals, genetically modified organisms, and the excessive use of water. There has also been an expansion of environmentally destructive mining activities in Mexico. There's been more mining in the last 10 years than in the whole colonial period. There have been higher levels of air and water pollution as associated with the growth of the maquiladora factories. And there has been a progressive weakening of domestic environmental safeguards and expanded powers to corporations to challenge environmental policies."

Today, the Obama administration, which did not even acknowledge the 20th anniversary of NAFTA, is eyeing a new, grander trade deal in the image of NAFTA called the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The TPP is a secret deal being negotiated by the Obama administration directly with various nations. Activists have called it "NAFTA on Steroids." Obama is seeking "fast-track authority" on the deal, whereby elected representatives would be allowed to vote on only the entire agreement without being party to negotiations over the details. WikiLeaks recently published a leaked draft chapter of the agreement that has confirmed some of the worst suspicions of activists opposing it. One expert called it "A Christmas wish list for major corporations."

If the implementation of NAFTA is any indication of how poor countries like Mexico have suffered under free-trade deals, Congress ought to fight the adoption of the TPP tooth and nail. The trouble is, as Perez-Rocha acknowledges, "Unfortunately I think that most Mexicans--and I would say the same here in the United States and Canada--don't have a very clear understanding of how NAFTA itself has affected their lives and the economy of our countries."