BY NOW MANY have read and been moved by the extraordinary mea culpa published in the Shreveport Times by a man named Marty Stroud III, who more than thirty years ago sent Glenn Ford to die for a crime he did not commit.

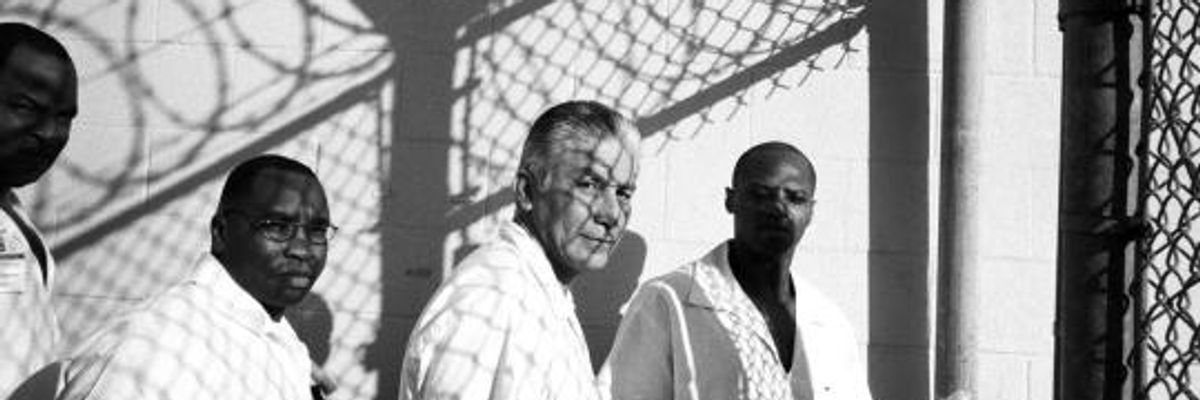

"How wrong was I," wrote Stroud, who as a young prosecutor convicted Ford, a black man, with the help of an all-white jury in Louisiana's Caddo Parish. Stroud's murder case against Ford was bankrupt on its face -- at trial, a key witness admitted in open court that her testimony had been a lie. Yet Ford didn't stand a chance. His court-appointed lawyers had never handled a criminal trial, let alone a capital case. He was sentenced to die, though fortunately never executed. After decades spent fighting to prove his innocence, Ford was was finally cleared after the DA's office revealed it had obtained exonerating evidence. But by the time he was released from prison last year, at 64, Ford was sick with cancer. Doctors say he has just months to live. Ford has spent his last days fighting for financial compensation, which the state has so far denied him. In his anguished letter to the Times, Stroud said that Ford "deserves every penny" for his lost freedom and expressed deep remorse "for all the misery I have caused him and his family."

Stroud's apology made headlines across the country. The National Registry of Exonerations called it "uniquely powerful and moving." In a culture that shields prosecutors from having to answer for even the most outrageous miscarriages of justice, Stroud's letter is indeed an astonishing read. Though no substitute for accountability - he denies any intentional misconduct -- Stroud lays bare the hubris that drives state actors to aggressively pursue even the most questionable convictions. "In 1984, I was 33 years old," Stroud writes. "I was arrogant, judgmental, narcissistic and very full of myself. I was not as interested in justice as I was in winning." Stroud recalls going out for drinks to celebrate Ford's death sentence, which he labels "sick." Not only because Ford turned out to be innocent. But because today Stroud believes that, as a fallible human being, he never should have had that kind of power to begin with. The death penalty, he writes, "is an abomination that continues to scar the fibers of this society."

Stroud's dramatic conversion, his revulsion at the memory of toasting a death sentence, echoes a story told by a different man, former Florida prison warden Ron McAndrew. On the morning after overseeing his first execution in 1996, McAndrew went out to the "traditional breakfast" with the execution team, at a Shoney's in Starke, FL, just 15 miles from the death chamber. "Everyone in the restaurant knew who we were and what we had just done," he wrote, "there were even a few 'high five signs.'" He spotted the defense attorney who had tried to save the life of the man he had just helped execute. "I saw my own sickness on her sad face," McAndrew wrote. The ritual felt wrong. "It was my first and my last traditional death breakfast." Later, Esquire would publish a profile of the former warden. It was titled "Ron McAndrew Is Done Killing People."

Others who once operated the machinery of death have reached similar epiphanies. Two years ago the Guardianpublished a sobering Q&A with Jerry Givens, a retired executioner who killed no fewer than 62 prisoners for the state of Virginia. Givens, a clearly traumatized man, said taking the job was the "biggest mistake I ever made." Today he serves on the board of Virginians Against the Death Penalty. Former Georgia warden Allen Ault, who presided over five executions and now speaks out against capital punishment, says he has "spent a lifetime regretting every moment and every killing." Jeanne Woodford, who gave the order for four executions as the warden of San Quentin Prison, later became the executive director of the abolitionist group Death Penalty Focus. In 2013, the New York Times ran an obituary for a warden-turned-academic who oversaw three executions at Mississippi's Parchman Farm. It included his nagging belief that one of the men may have been innocent. In its headline the Times remembered him as "Donald Cabana, Warden Who Loathed the Death Penalty."

These are transformative figures. Their accounts, while powerful on their own, are important in the space they create for others to change as well -- perhaps even some still working inside the system they have since disavowed. As Americans increasingly question the death penalty amid new exonerations and botched executions, we can probably expect -- and should encourage -- more of these stories.

Read the full article at The Intercept.