As the rest of the country goes to war over standardized tests, California may be showing it can do school improvement without them. (Image: WIFQE/Facebook)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

As the rest of the country goes to war over standardized tests, California may be showing it can do school improvement without them. (Image: WIFQE/Facebook)

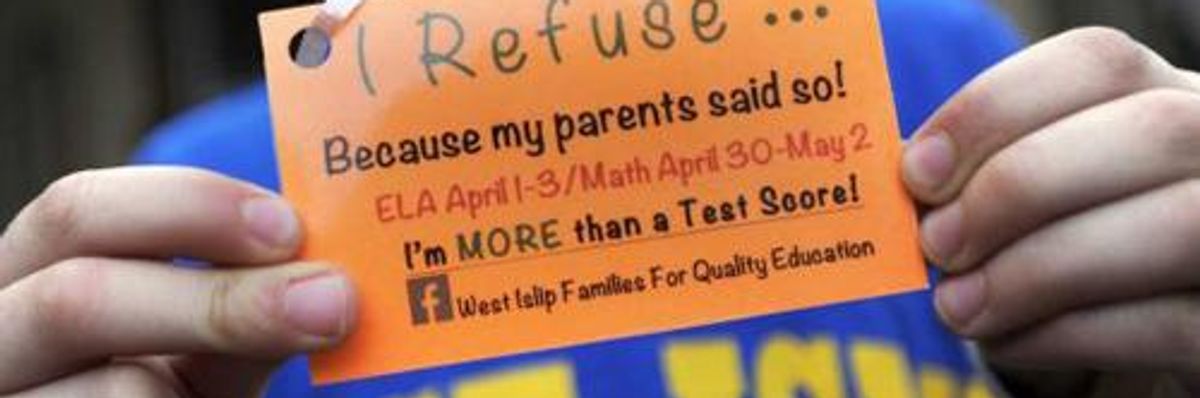

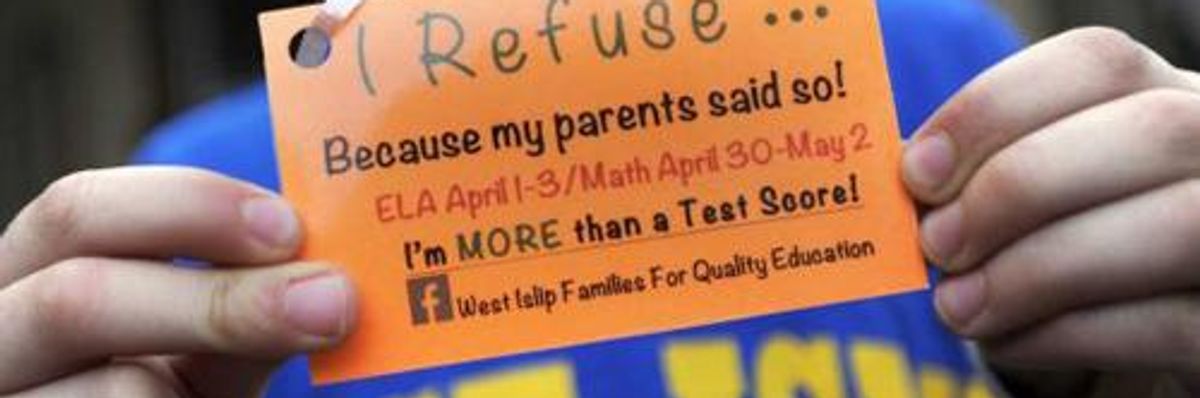

The movement to boycott standardized testing has caught the media totally by surprise. The mostly parent-led effort started with Facebook pages and neighborhood meetings has grown into a firestorm of resistance.

As the Associated Press reported this week, "This 'opt-out' movement remains scattered but is growing fast." The article points to New York - where perhaps as many as 200,000 students recently sat out the standardized tests - but also mentions strong opt-out movements in New Jersey, Maine, New Mexico, Oregon, and Pennsylvania.

Even education policy influentials who have long advocated for an accountability system driven by standardized tests have been shaken by the resounding opposition to their policies.

Meanwhile, in Washington, DC, momentum is growing behind a US Senate bill rewriting No Child Left Behind legislation that governs national education policy. As Zoe Carpenter describes for The Nation, the new bill, the Every Child Achieves Act, isn't exactly "a stake through the heart of NCLB," but it likely puts the accountability mandates of NCLB into a state of flux in which federal enforcement of Adequate Yearly Progress would end and states would have more leeway in crafting their own accountability measures.

It would seem that at a time, such as now, when the nation's education policy is in such disarray, and incoherence rules the day, it would be good to pivot to alternatives that might provide a more positive path forward. Indeed, such an alternative approach is at hand.

Lessons From An 'Outlier'

California - the state with by far the most K-12 students, one in eight - has started to take education policy in a different direction.

As Claremont Graduate University professor Charles Taylor Kerchner explains in an op-ed in Education Week, the Golden State is an "outlier" when it comes to education, veering sharply away from policies pushed by President Barak Obama and his Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

"The state has refused to sign on to the test-score-accountability provisions of the federal agenda," Kerchner writes. And, "The state legislature has terminated its old statewide testing system altogether and suspended its single indicator system."

Also, at a time when politicians pay more lip service to inequity in the country, California's education policy has actually taken steps to address that problem. "The state has coupled the revival of its financial fortunes with a revolutionary change in how it spends its education dollars," Kerchner explains. Through the state's recently enacted local-control funding formula, "substantial fiscal control" is now in the hands of local school districts, and "districts with low-income students, English-language learners, and foster youths receive 20 percent more in the current version of the formula. Those where 55 percent of students fall into one or more high-needs categories will get an additional grant."

These changes have turned "the education policy of the last four decades on its head," Kerchner argues, and instead of fiscal austerity and top-down accountability, financial support for local schools has grown, local authorities have been empowered to create change, and trust and verification have taken over from rigid oversight.

A Build-And-Support Approach

The California Model is described by former state school chief Bill Honig as a Build-and-Support approach, as opposed to the Test-and-Punish policy carried out since the advent of NCLB.

In my recent interview with Honig at Salon, he describes Build-and-Support as consisting of

Honig describes how his state has avoided many of the emotional conflicts that have consumed education policy decision making elsewhere by divorcing policy innovations, such as Common Core Standards, from test-based accountability. "We wanted instruction, not testing, to drive the effort," he explains. "The state also is developing an accountability system that has broader measures than just annual tests and will be primarily aimed at feeding information back to improvement efforts at the school and district.

Honig concludes. "Our path forward is what the best educational and management and educational scholarship has advised, irrefutable evidence has supported, and the most successful schools and districts here and abroad have adopted."

Choosing The Right Drivers For Improvement

Much of the philosophy behind the California Model is derived from the work of Michael Fullan, who is an acclaimed author and consultant in the field of education governance and reform.

Fullan contends American education policy since NCLB has been obsessed with "the wrong drivers." In his studies of education systems around the world, he finds, "In the rush to move forward, leaders, especially from countries that have not been progressing, tend to choose the wrong drivers. Such ineffective drivers fundamentally miss the target."

Four "culprits" Fullan finds that "make matters significantly worse" are over-emphasizing accountability and test results, promoting individual rather than group solutions, substituting technology for good instruction, and choosing fragmented strategies instead of systemic strategies to improve the system.

Although these drivers can be "components" of reform, Fullan argues, it is "a mistake to lead with them. Countries that do lead with them (efforts such as are currently underway in the US and Australia, for example) will fail to achieve whole system reform."

Alternatively, Fullan calls for policies that lead with "right drivers" that are evident in countries that consistently score highest on international assessments of academic achievement: Korea, Finland, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Canada.

The right drivers Fullan finds at work in high-performing countries are

These four improvement drivers, Fullan insists, are "the crucial elements for whole system reform."

Education policy leaders in California seem to agree and have started acting on these ideas.

Beyond NCLB Accountability

To move toward an education policy with the right drivers, California has moved beyond the notion of accountability enforced by NCLB.

As Kerchner describes in a blog post for Education Week, "In an era where Congress is deadlocked, California is pushing to create new, multiple measure accountability measures."

Kerchner explains how his state has gone beyond a myopic attention to test scores to look at other kinds of results, such as "tracking progress of English Learners," student preparedness for college, suspension and expulsion rates, chronic absenteeism, dropout rates, graduation rates, and access to a well-rounded curriculum.

This approach to accountability is echoed in calls from National Education Association president Lily Eskelsen Garcia. Garcia and the NEA call for any revision of NCLB to include an "opportunity dashboard" similar to what California is pursuing. In a letter she sent to Secretary Duncan, she states, "We need a new generation accountability system that includes an 'opportunity dashboard' -indicators of school quality that support learning."

The "dashboard" she and NEA propose would require states to go beyond merely tracking test scores and show they provide supports for student learning. Supports-based measures on the dashboard could include evidence that students have access to advanced coursework, that fully qualified teachers are employed in all classrooms, that arts and athletic programs are included in the curriculum, and that school support personnel - such as school counselors, nurses, and reading specialists - are provided for students who need them.

An Alternative, If We Want One

As the rest of the country goes to war over standardized tests, California may be showing it can do school improvement without them.

That's the conclusion reached by Pomona College professor David Menefee-Libey who shares blog space with Kerchner at Education Week.

California's move to its new policy of local control of finance and accountability, Menefee-Libey explains, has led to "a new multiple-indicator accountability system" that "fundamentally changes the politics of finance and accountability, substituting local politics and grassroots agency for state-driven mandates and compliance reviews."

This "Post-NCLB Era," his words, is not without its complications. In my interview with Honig, he admits new policies have not yet been implemented uniformly across the state, and much is still "a work in progress" that will require "adjustments."

Other obstacles to progress rear their ugly heads as well. The state is still embroiled in a political conflict over teacher tenure. Efforts to privatize public schools, rather than build their capacity and support them, continue to be pushed by wealthy foundations and investors. Even more important, the state faces massive problems with inequality that threaten the education system from the outside.

Nevertheless, as the rest of the nation plunges further into the conflict over NCLB-era accountability, California is showing us an alternative is available - if we want one.

Common Dreams is powered by optimists who believe in the power of informed and engaged citizens to ignite and enact change to make the world a better place. We're hundreds of thousands strong, but every single supporter makes the difference. Your contribution supports this bold media model—free, independent, and dedicated to reporting the facts every day. Stand with us in the fight for economic equality, social justice, human rights, and a more sustainable future. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover the issues the corporate media never will. |

The movement to boycott standardized testing has caught the media totally by surprise. The mostly parent-led effort started with Facebook pages and neighborhood meetings has grown into a firestorm of resistance.

As the Associated Press reported this week, "This 'opt-out' movement remains scattered but is growing fast." The article points to New York - where perhaps as many as 200,000 students recently sat out the standardized tests - but also mentions strong opt-out movements in New Jersey, Maine, New Mexico, Oregon, and Pennsylvania.

Even education policy influentials who have long advocated for an accountability system driven by standardized tests have been shaken by the resounding opposition to their policies.

Meanwhile, in Washington, DC, momentum is growing behind a US Senate bill rewriting No Child Left Behind legislation that governs national education policy. As Zoe Carpenter describes for The Nation, the new bill, the Every Child Achieves Act, isn't exactly "a stake through the heart of NCLB," but it likely puts the accountability mandates of NCLB into a state of flux in which federal enforcement of Adequate Yearly Progress would end and states would have more leeway in crafting their own accountability measures.

It would seem that at a time, such as now, when the nation's education policy is in such disarray, and incoherence rules the day, it would be good to pivot to alternatives that might provide a more positive path forward. Indeed, such an alternative approach is at hand.

Lessons From An 'Outlier'

California - the state with by far the most K-12 students, one in eight - has started to take education policy in a different direction.

As Claremont Graduate University professor Charles Taylor Kerchner explains in an op-ed in Education Week, the Golden State is an "outlier" when it comes to education, veering sharply away from policies pushed by President Barak Obama and his Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

"The state has refused to sign on to the test-score-accountability provisions of the federal agenda," Kerchner writes. And, "The state legislature has terminated its old statewide testing system altogether and suspended its single indicator system."

Also, at a time when politicians pay more lip service to inequity in the country, California's education policy has actually taken steps to address that problem. "The state has coupled the revival of its financial fortunes with a revolutionary change in how it spends its education dollars," Kerchner explains. Through the state's recently enacted local-control funding formula, "substantial fiscal control" is now in the hands of local school districts, and "districts with low-income students, English-language learners, and foster youths receive 20 percent more in the current version of the formula. Those where 55 percent of students fall into one or more high-needs categories will get an additional grant."

These changes have turned "the education policy of the last four decades on its head," Kerchner argues, and instead of fiscal austerity and top-down accountability, financial support for local schools has grown, local authorities have been empowered to create change, and trust and verification have taken over from rigid oversight.

A Build-And-Support Approach

The California Model is described by former state school chief Bill Honig as a Build-and-Support approach, as opposed to the Test-and-Punish policy carried out since the advent of NCLB.

In my recent interview with Honig at Salon, he describes Build-and-Support as consisting of

Honig describes how his state has avoided many of the emotional conflicts that have consumed education policy decision making elsewhere by divorcing policy innovations, such as Common Core Standards, from test-based accountability. "We wanted instruction, not testing, to drive the effort," he explains. "The state also is developing an accountability system that has broader measures than just annual tests and will be primarily aimed at feeding information back to improvement efforts at the school and district.

Honig concludes. "Our path forward is what the best educational and management and educational scholarship has advised, irrefutable evidence has supported, and the most successful schools and districts here and abroad have adopted."

Choosing The Right Drivers For Improvement

Much of the philosophy behind the California Model is derived from the work of Michael Fullan, who is an acclaimed author and consultant in the field of education governance and reform.

Fullan contends American education policy since NCLB has been obsessed with "the wrong drivers." In his studies of education systems around the world, he finds, "In the rush to move forward, leaders, especially from countries that have not been progressing, tend to choose the wrong drivers. Such ineffective drivers fundamentally miss the target."

Four "culprits" Fullan finds that "make matters significantly worse" are over-emphasizing accountability and test results, promoting individual rather than group solutions, substituting technology for good instruction, and choosing fragmented strategies instead of systemic strategies to improve the system.

Although these drivers can be "components" of reform, Fullan argues, it is "a mistake to lead with them. Countries that do lead with them (efforts such as are currently underway in the US and Australia, for example) will fail to achieve whole system reform."

Alternatively, Fullan calls for policies that lead with "right drivers" that are evident in countries that consistently score highest on international assessments of academic achievement: Korea, Finland, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Canada.

The right drivers Fullan finds at work in high-performing countries are

These four improvement drivers, Fullan insists, are "the crucial elements for whole system reform."

Education policy leaders in California seem to agree and have started acting on these ideas.

Beyond NCLB Accountability

To move toward an education policy with the right drivers, California has moved beyond the notion of accountability enforced by NCLB.

As Kerchner describes in a blog post for Education Week, "In an era where Congress is deadlocked, California is pushing to create new, multiple measure accountability measures."

Kerchner explains how his state has gone beyond a myopic attention to test scores to look at other kinds of results, such as "tracking progress of English Learners," student preparedness for college, suspension and expulsion rates, chronic absenteeism, dropout rates, graduation rates, and access to a well-rounded curriculum.

This approach to accountability is echoed in calls from National Education Association president Lily Eskelsen Garcia. Garcia and the NEA call for any revision of NCLB to include an "opportunity dashboard" similar to what California is pursuing. In a letter she sent to Secretary Duncan, she states, "We need a new generation accountability system that includes an 'opportunity dashboard' -indicators of school quality that support learning."

The "dashboard" she and NEA propose would require states to go beyond merely tracking test scores and show they provide supports for student learning. Supports-based measures on the dashboard could include evidence that students have access to advanced coursework, that fully qualified teachers are employed in all classrooms, that arts and athletic programs are included in the curriculum, and that school support personnel - such as school counselors, nurses, and reading specialists - are provided for students who need them.

An Alternative, If We Want One

As the rest of the country goes to war over standardized tests, California may be showing it can do school improvement without them.

That's the conclusion reached by Pomona College professor David Menefee-Libey who shares blog space with Kerchner at Education Week.

California's move to its new policy of local control of finance and accountability, Menefee-Libey explains, has led to "a new multiple-indicator accountability system" that "fundamentally changes the politics of finance and accountability, substituting local politics and grassroots agency for state-driven mandates and compliance reviews."

This "Post-NCLB Era," his words, is not without its complications. In my interview with Honig, he admits new policies have not yet been implemented uniformly across the state, and much is still "a work in progress" that will require "adjustments."

Other obstacles to progress rear their ugly heads as well. The state is still embroiled in a political conflict over teacher tenure. Efforts to privatize public schools, rather than build their capacity and support them, continue to be pushed by wealthy foundations and investors. Even more important, the state faces massive problems with inequality that threaten the education system from the outside.

Nevertheless, as the rest of the nation plunges further into the conflict over NCLB-era accountability, California is showing us an alternative is available - if we want one.

The movement to boycott standardized testing has caught the media totally by surprise. The mostly parent-led effort started with Facebook pages and neighborhood meetings has grown into a firestorm of resistance.

As the Associated Press reported this week, "This 'opt-out' movement remains scattered but is growing fast." The article points to New York - where perhaps as many as 200,000 students recently sat out the standardized tests - but also mentions strong opt-out movements in New Jersey, Maine, New Mexico, Oregon, and Pennsylvania.

Even education policy influentials who have long advocated for an accountability system driven by standardized tests have been shaken by the resounding opposition to their policies.

Meanwhile, in Washington, DC, momentum is growing behind a US Senate bill rewriting No Child Left Behind legislation that governs national education policy. As Zoe Carpenter describes for The Nation, the new bill, the Every Child Achieves Act, isn't exactly "a stake through the heart of NCLB," but it likely puts the accountability mandates of NCLB into a state of flux in which federal enforcement of Adequate Yearly Progress would end and states would have more leeway in crafting their own accountability measures.

It would seem that at a time, such as now, when the nation's education policy is in such disarray, and incoherence rules the day, it would be good to pivot to alternatives that might provide a more positive path forward. Indeed, such an alternative approach is at hand.

Lessons From An 'Outlier'

California - the state with by far the most K-12 students, one in eight - has started to take education policy in a different direction.

As Claremont Graduate University professor Charles Taylor Kerchner explains in an op-ed in Education Week, the Golden State is an "outlier" when it comes to education, veering sharply away from policies pushed by President Barak Obama and his Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

"The state has refused to sign on to the test-score-accountability provisions of the federal agenda," Kerchner writes. And, "The state legislature has terminated its old statewide testing system altogether and suspended its single indicator system."

Also, at a time when politicians pay more lip service to inequity in the country, California's education policy has actually taken steps to address that problem. "The state has coupled the revival of its financial fortunes with a revolutionary change in how it spends its education dollars," Kerchner explains. Through the state's recently enacted local-control funding formula, "substantial fiscal control" is now in the hands of local school districts, and "districts with low-income students, English-language learners, and foster youths receive 20 percent more in the current version of the formula. Those where 55 percent of students fall into one or more high-needs categories will get an additional grant."

These changes have turned "the education policy of the last four decades on its head," Kerchner argues, and instead of fiscal austerity and top-down accountability, financial support for local schools has grown, local authorities have been empowered to create change, and trust and verification have taken over from rigid oversight.

A Build-And-Support Approach

The California Model is described by former state school chief Bill Honig as a Build-and-Support approach, as opposed to the Test-and-Punish policy carried out since the advent of NCLB.

In my recent interview with Honig at Salon, he describes Build-and-Support as consisting of

Honig describes how his state has avoided many of the emotional conflicts that have consumed education policy decision making elsewhere by divorcing policy innovations, such as Common Core Standards, from test-based accountability. "We wanted instruction, not testing, to drive the effort," he explains. "The state also is developing an accountability system that has broader measures than just annual tests and will be primarily aimed at feeding information back to improvement efforts at the school and district.

Honig concludes. "Our path forward is what the best educational and management and educational scholarship has advised, irrefutable evidence has supported, and the most successful schools and districts here and abroad have adopted."

Choosing The Right Drivers For Improvement

Much of the philosophy behind the California Model is derived from the work of Michael Fullan, who is an acclaimed author and consultant in the field of education governance and reform.

Fullan contends American education policy since NCLB has been obsessed with "the wrong drivers." In his studies of education systems around the world, he finds, "In the rush to move forward, leaders, especially from countries that have not been progressing, tend to choose the wrong drivers. Such ineffective drivers fundamentally miss the target."

Four "culprits" Fullan finds that "make matters significantly worse" are over-emphasizing accountability and test results, promoting individual rather than group solutions, substituting technology for good instruction, and choosing fragmented strategies instead of systemic strategies to improve the system.

Although these drivers can be "components" of reform, Fullan argues, it is "a mistake to lead with them. Countries that do lead with them (efforts such as are currently underway in the US and Australia, for example) will fail to achieve whole system reform."

Alternatively, Fullan calls for policies that lead with "right drivers" that are evident in countries that consistently score highest on international assessments of academic achievement: Korea, Finland, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Canada.

The right drivers Fullan finds at work in high-performing countries are

These four improvement drivers, Fullan insists, are "the crucial elements for whole system reform."

Education policy leaders in California seem to agree and have started acting on these ideas.

Beyond NCLB Accountability

To move toward an education policy with the right drivers, California has moved beyond the notion of accountability enforced by NCLB.

As Kerchner describes in a blog post for Education Week, "In an era where Congress is deadlocked, California is pushing to create new, multiple measure accountability measures."

Kerchner explains how his state has gone beyond a myopic attention to test scores to look at other kinds of results, such as "tracking progress of English Learners," student preparedness for college, suspension and expulsion rates, chronic absenteeism, dropout rates, graduation rates, and access to a well-rounded curriculum.

This approach to accountability is echoed in calls from National Education Association president Lily Eskelsen Garcia. Garcia and the NEA call for any revision of NCLB to include an "opportunity dashboard" similar to what California is pursuing. In a letter she sent to Secretary Duncan, she states, "We need a new generation accountability system that includes an 'opportunity dashboard' -indicators of school quality that support learning."

The "dashboard" she and NEA propose would require states to go beyond merely tracking test scores and show they provide supports for student learning. Supports-based measures on the dashboard could include evidence that students have access to advanced coursework, that fully qualified teachers are employed in all classrooms, that arts and athletic programs are included in the curriculum, and that school support personnel - such as school counselors, nurses, and reading specialists - are provided for students who need them.

An Alternative, If We Want One

As the rest of the country goes to war over standardized tests, California may be showing it can do school improvement without them.

That's the conclusion reached by Pomona College professor David Menefee-Libey who shares blog space with Kerchner at Education Week.

California's move to its new policy of local control of finance and accountability, Menefee-Libey explains, has led to "a new multiple-indicator accountability system" that "fundamentally changes the politics of finance and accountability, substituting local politics and grassroots agency for state-driven mandates and compliance reviews."

This "Post-NCLB Era," his words, is not without its complications. In my interview with Honig, he admits new policies have not yet been implemented uniformly across the state, and much is still "a work in progress" that will require "adjustments."

Other obstacles to progress rear their ugly heads as well. The state is still embroiled in a political conflict over teacher tenure. Efforts to privatize public schools, rather than build their capacity and support them, continue to be pushed by wealthy foundations and investors. Even more important, the state faces massive problems with inequality that threaten the education system from the outside.

Nevertheless, as the rest of the nation plunges further into the conflict over NCLB-era accountability, California is showing us an alternative is available - if we want one.