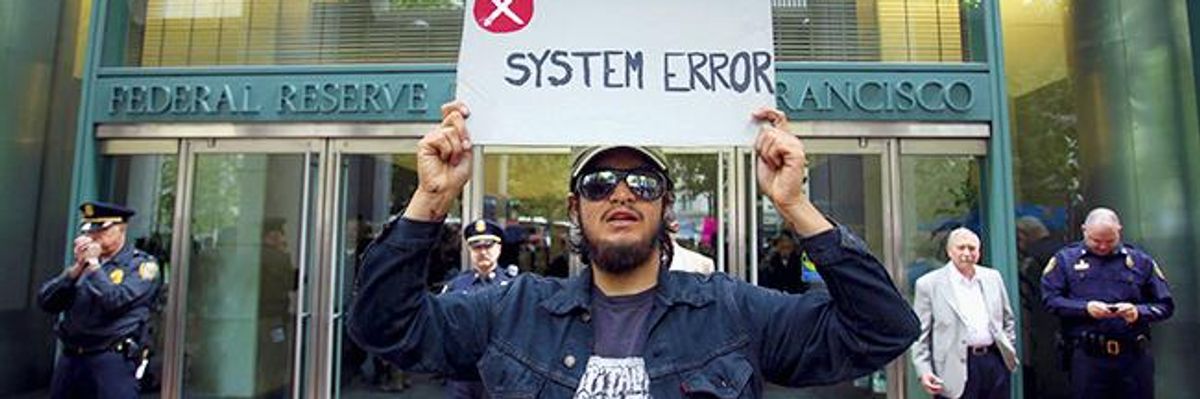

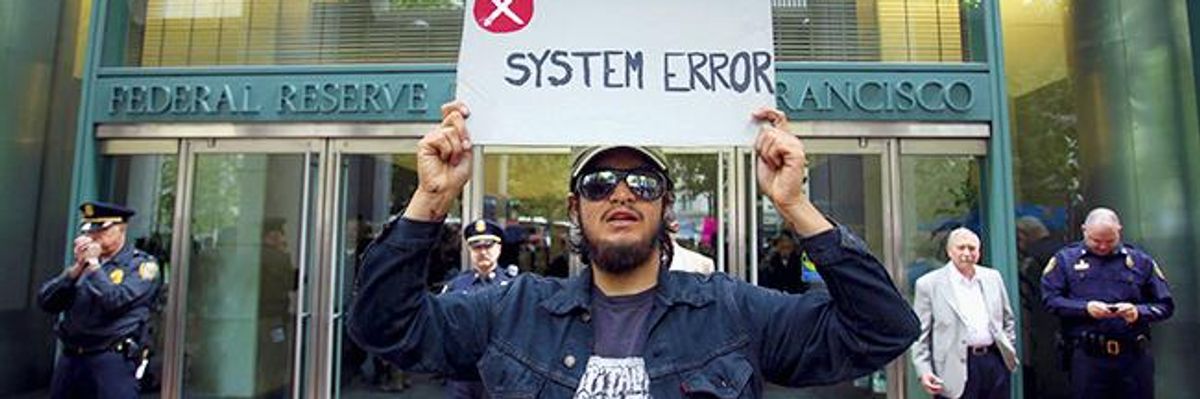

'The dangers of concentrated wealth and power have once again captured the public imagination,' writes Korten.

(Photo via Shutterstock)

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

'The dangers of concentrated wealth and power have once again captured the public imagination,' writes Korten.

You may have noticed. In our political discourse, suddenly the term "populism" is everywhere.

In April, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid joined 5,000 other political leaders in a call to make "big, bold, economic-populist ideas" the center of the 2016 presidential campaign. Outlets as disparate as The New York Times, The Nation, Time, and Fox News apply the label to politicians across the political spectrum.

Elizabeth Warren, known for her fiery critiques of Wall Street, is termed a populist. Hillary Clinton has a new-found interest in economic populism; Bernie Sanders has long worn the label. Even right-wing firebrand Ted Cruz gets the label, and Bobby Jindal applies it to himself. As Robert Borosage, head of the Campaign for America's Future, put it, "We live in a populist moment."

The term populist harkens back to the movement that formed in the 1880s in response to the extremes of wealth and power in the Gilded Age. As Lawrence Goodwyn describes in his book The Populist Moment, farmers found themselves in perpetual debt at the hands of local merchants and corporate monopolies. Many lost their land. They decried the concentrated wealth of the banks and big business and advocated policies that favored working people over the elites. Millions were attracted by the idea of forming cooperatives where they could buy goods and sell their produce at fair prices.

By 1892, the movement had broadened to include urban workers and became the People's Party. At their founding convention, they enthusiastically embraced a platform that included a progressive income tax, the secret ballot, direct election of senators, the right of citizens to create initiatives and referenda, shorter hours for workers, antitrust legislation, postal savings banks, and shifting the power to create money from bankers to government.

In the 1896 presidential race, the People's Party made common cause with William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee. Bryan was defeated, and it looked like the populists had lost.

In fact, their ideas were only beginning to take hold. The next three decades saw much of their 1892 platform enacted. Their hope for cooperatives flowered in much of the Midwest. But they didn't get everything they hoped for and they didn't break the bankers' hold on creating money.

Since the heyday of populism, many of its policies have been watered down and the flood of money in politics has eviscerated the effects of others. Now, the concentration of wealth and power is much like that of the Gilded Age. Americans are again awash in debt.

So we should not be surprised that populist ideas are making a comeback. We hear those ideas in the Occupy movement's demands to rein in Wall Street and rectify our country's extreme inequality. We see them in the grassroots opposition to the Supreme Court's Citizens United decision that allows corporations to spend at will on our political process. And they are echoed by the millions mobilizing for a $15-an-hour minimum wage. The dangers of concentrated wealth and power have once again captured the public imagination.

The prospect of enacting a populist agenda is daunting. The power of Wall Street banks, giant oil companies, big pharma, and big ag seems overwhelming.

But the original populists also faced daunting challenges--cotton monopolies, Standard Oil, the railroads, and a financial system rigged against them. They came together, learned the issues, and shaped the nation. Now it is our turn to advance the populist call for economic fairness, real democracy, and a dignified life for all.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

You may have noticed. In our political discourse, suddenly the term "populism" is everywhere.

In April, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid joined 5,000 other political leaders in a call to make "big, bold, economic-populist ideas" the center of the 2016 presidential campaign. Outlets as disparate as The New York Times, The Nation, Time, and Fox News apply the label to politicians across the political spectrum.

Elizabeth Warren, known for her fiery critiques of Wall Street, is termed a populist. Hillary Clinton has a new-found interest in economic populism; Bernie Sanders has long worn the label. Even right-wing firebrand Ted Cruz gets the label, and Bobby Jindal applies it to himself. As Robert Borosage, head of the Campaign for America's Future, put it, "We live in a populist moment."

The term populist harkens back to the movement that formed in the 1880s in response to the extremes of wealth and power in the Gilded Age. As Lawrence Goodwyn describes in his book The Populist Moment, farmers found themselves in perpetual debt at the hands of local merchants and corporate monopolies. Many lost their land. They decried the concentrated wealth of the banks and big business and advocated policies that favored working people over the elites. Millions were attracted by the idea of forming cooperatives where they could buy goods and sell their produce at fair prices.

By 1892, the movement had broadened to include urban workers and became the People's Party. At their founding convention, they enthusiastically embraced a platform that included a progressive income tax, the secret ballot, direct election of senators, the right of citizens to create initiatives and referenda, shorter hours for workers, antitrust legislation, postal savings banks, and shifting the power to create money from bankers to government.

In the 1896 presidential race, the People's Party made common cause with William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee. Bryan was defeated, and it looked like the populists had lost.

In fact, their ideas were only beginning to take hold. The next three decades saw much of their 1892 platform enacted. Their hope for cooperatives flowered in much of the Midwest. But they didn't get everything they hoped for and they didn't break the bankers' hold on creating money.

Since the heyday of populism, many of its policies have been watered down and the flood of money in politics has eviscerated the effects of others. Now, the concentration of wealth and power is much like that of the Gilded Age. Americans are again awash in debt.

So we should not be surprised that populist ideas are making a comeback. We hear those ideas in the Occupy movement's demands to rein in Wall Street and rectify our country's extreme inequality. We see them in the grassroots opposition to the Supreme Court's Citizens United decision that allows corporations to spend at will on our political process. And they are echoed by the millions mobilizing for a $15-an-hour minimum wage. The dangers of concentrated wealth and power have once again captured the public imagination.

The prospect of enacting a populist agenda is daunting. The power of Wall Street banks, giant oil companies, big pharma, and big ag seems overwhelming.

But the original populists also faced daunting challenges--cotton monopolies, Standard Oil, the railroads, and a financial system rigged against them. They came together, learned the issues, and shaped the nation. Now it is our turn to advance the populist call for economic fairness, real democracy, and a dignified life for all.

You may have noticed. In our political discourse, suddenly the term "populism" is everywhere.

In April, Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid joined 5,000 other political leaders in a call to make "big, bold, economic-populist ideas" the center of the 2016 presidential campaign. Outlets as disparate as The New York Times, The Nation, Time, and Fox News apply the label to politicians across the political spectrum.

Elizabeth Warren, known for her fiery critiques of Wall Street, is termed a populist. Hillary Clinton has a new-found interest in economic populism; Bernie Sanders has long worn the label. Even right-wing firebrand Ted Cruz gets the label, and Bobby Jindal applies it to himself. As Robert Borosage, head of the Campaign for America's Future, put it, "We live in a populist moment."

The term populist harkens back to the movement that formed in the 1880s in response to the extremes of wealth and power in the Gilded Age. As Lawrence Goodwyn describes in his book The Populist Moment, farmers found themselves in perpetual debt at the hands of local merchants and corporate monopolies. Many lost their land. They decried the concentrated wealth of the banks and big business and advocated policies that favored working people over the elites. Millions were attracted by the idea of forming cooperatives where they could buy goods and sell their produce at fair prices.

By 1892, the movement had broadened to include urban workers and became the People's Party. At their founding convention, they enthusiastically embraced a platform that included a progressive income tax, the secret ballot, direct election of senators, the right of citizens to create initiatives and referenda, shorter hours for workers, antitrust legislation, postal savings banks, and shifting the power to create money from bankers to government.

In the 1896 presidential race, the People's Party made common cause with William Jennings Bryan, the Democratic nominee. Bryan was defeated, and it looked like the populists had lost.

In fact, their ideas were only beginning to take hold. The next three decades saw much of their 1892 platform enacted. Their hope for cooperatives flowered in much of the Midwest. But they didn't get everything they hoped for and they didn't break the bankers' hold on creating money.

Since the heyday of populism, many of its policies have been watered down and the flood of money in politics has eviscerated the effects of others. Now, the concentration of wealth and power is much like that of the Gilded Age. Americans are again awash in debt.

So we should not be surprised that populist ideas are making a comeback. We hear those ideas in the Occupy movement's demands to rein in Wall Street and rectify our country's extreme inequality. We see them in the grassroots opposition to the Supreme Court's Citizens United decision that allows corporations to spend at will on our political process. And they are echoed by the millions mobilizing for a $15-an-hour minimum wage. The dangers of concentrated wealth and power have once again captured the public imagination.

The prospect of enacting a populist agenda is daunting. The power of Wall Street banks, giant oil companies, big pharma, and big ag seems overwhelming.

But the original populists also faced daunting challenges--cotton monopolies, Standard Oil, the railroads, and a financial system rigged against them. They came together, learned the issues, and shaped the nation. Now it is our turn to advance the populist call for economic fairness, real democracy, and a dignified life for all.