On December 16th 2009, two days before the Copenhagen Accord was issued, when there was still a scant sliver of hope for a legally binding treaty, the Prime Minister of Grenada Tillman Thomas took the microphone and called on world leaders to cement a deal with a 1.5 Celsius target.

Thomas called on all countries to protect low-lying island nations from being "swept away in the king wave of climate change" by keeping "temperature increases to well below 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels."

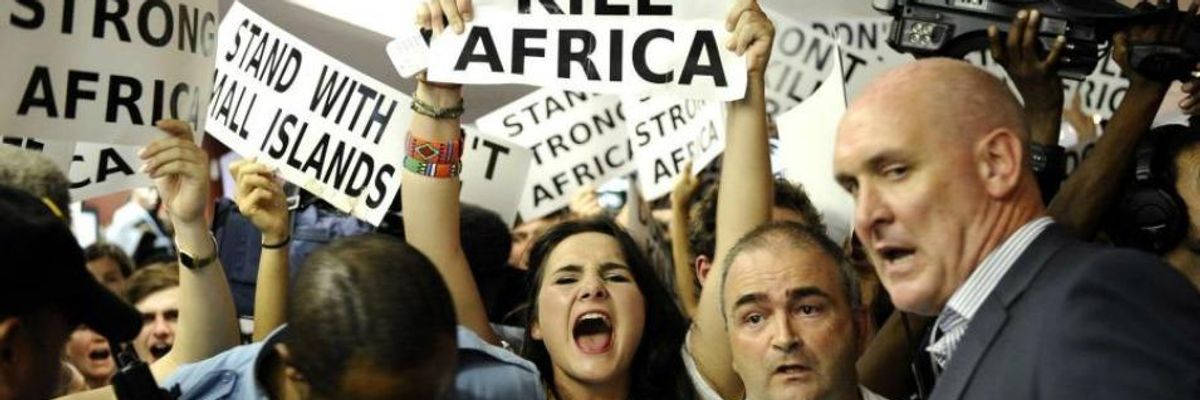

Thomas was speaking for the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), a coalition of 44 island countries drawn from all the oceans of the world. By the time Thomas took the microphone, AOSIS had turned "1.5 to Stay Alive" into a unifying rallying cry for over 100 nations - searing an alliance between the Islands and the African bloc.

Desmond Tutu wrote, "A global goal of about 2 degrees is to condemn Africa to incineration."

2 degrees represented, in a word, death. Or, as Bruno Sekoli of Lesotho, the then chair of the Least Developed Countries (LCDs) group, put it: 2 degrees would mean "unmanageable consequences - it will leave millions of people suffering from hunger, diseases, floods and water shortages."

1.5 was the number that represented survival, hope, and unleashing a kind of global World War II-level mobilization to move beyond fossil fuels. (After the attack on Pearl Harbor, it took 10 weeks for the US to completely halt car manufacturing, and begin the rapid switch to making aircraft bombers and heavy tanks for the war effort. Those 10 weeks also included the Christmas holiday season.)

The Fall of 1.5degC

Two days after the Prime Minister of Grenada made his plea to the world, President Obama took an overnight flight into Copenhagen and led the push for the Copenhagen Accord, a non-binding treaty with a 2 degree Celsius target at its masthead.

It's been nearly 5 years since Copenhagen, and now 2 degrees is the darling target for the UN, developed countries, and even many climate activists. It's a number that has pushed its way into the cultural mainstream, not unlike how the 350 ppm target did in 2009. CNN's John Sutter wrote this past May that 2 degrees is "the most important number you've never heard of." Sutter even launched a fully dedicated CNN column for how we achieve 2degC--named, simply, "twodeg."

In the last week, VICE, MTV, & Mashable all published articles mentioning the 2 degrees target, without a whisper of 1.5. Wire reports in the AP and Reuters also regularly leave out 1.5 degrees when defining success in Paris.

So: what happened to "1.5 to Stay Alive"?

Well, for starters, 141 countries signed onto the Copenhagen Accord - adding their weight to the 2 degrees target. Getting that many countries to agree to something is rare, and creates its own kind of momentum.

That momentum was further strengthened at the Cancun talks in 2010, and the Durban talks in 2011, while a review of the science of 1.5 degrees was consistently punted to some later date.

Strategy of 2degC

Two and a half years after Copenhagen, 2 degrees picked up further steam with Bill McKibben's 2012 Rolling Stone article, "Global Warming's Terrifying New Math."

In the piece, McKibben lays out the flaws of the 2 degrees target. McKibben writes that "2 degrees is far too lenient a target" and amplifies then-NASA's chief climate scientist James Hansen who said: "two degrees of warming is actually a prescription for long-term disaster." McKibben goes on to point out the consequences of 2 degrees: Island nations would "flat-out disappear," and African nations would completely dry up.

Despite those intense warnings, however, McKibben ends with a kind of reluctant support of the number, writing, "it's fair to say that it's [2 degrees] the only thing about climate change the world has settled on....The official position of planet Earth at the moment is that we can't raise the temperature more than two degrees Celsius - it's become the bottomest of bottom lines. Two degrees."

Inspired by that Rolling Stone article, 2 degrees would go on to form the bedrock goal for the fossil fuel divestment movement that has since swept the world. 350.org's launch website for divestment exclaimed, "It's simple math: we can emit 565 more gigatons of carbon dioxide and stay below 2degC of warming -- anything more than that risks catastrophe for life on earth."

In April of this year, Naomi Klein told French news site BastaMag that 2 degrees is "a target that is already a very dangerous one for many communities. But it provides us with a global carbon budget."

The strategic purpose of shouldering the 2 degrees target seems rather clear: since world leaders already agree on 2 degrees - and since those leaders have historically been inclined to set the Earth on a course of varying degrees of hellish intensity far beyond 2 degrees, it's a chance to hold their feet to the fire.

You might say: You can leverage consensus far better than you can leverage a lofty hope.

UN Doubles Down on 2 Degrees; UN Scientists Cry Out

By now, 150 countries have submitted their pledges for the Paris climate talks, with the European Union saying it would only back a deal with 2 degrees cemented as its goal.

UN climate leadership is also gung-ho for 2 degrees even as the UN climate chief Christiana Figueres is worried pledges so far won't cut it, and will lead to a 3 degrees world.

Whenever a country submits their pledges for Paris, the UNFCCC (the UN climate body) issues a stock press announcement to celebrate and uses it as a chance to highlight the 2 degree goal.

Curiously, when countries submit pledges calling for the more audacious 1.5 target, the response is much different. The UN's press announcement regarding Belize, for example, counters the country's ambition by saying the Paris agreement will "empower all countries to act to prevent average global temperatures rising above 2 degrees Celsius."

More curious still, this past June the UN's very own special expert investigation, tasked with examining the difference between a 1.5oC and 2oC limit, concluded that 2 degrees is "inadequate" as a safe limit and that 2 degrees could "hardly be seen as a 'guardrail' protecting us fully from dangerous anthropogenic interference." Two degrees would threaten "the very existence of some atoll nations" whereas 1.5 degrees may keep sea level rise to below 1 meter, perhaps preventing the outright drowning of countries like Tuvalu and the Maldives.

Dr. Petra Tschakert, a member of the UN's 1.5 vs. 2 investigative team (and a co-author of the UN's latest climate report) points out that "the 2degC target will carry more extreme weather events such as floods, droughts, and heat waves"--calling all of those "utterly unacceptable risks...for poor and marginalized communities."

The UN working group in charge of reviewing their experts' findings on the disparities between 1.5 and 2 degrees is set to make a final call in the midst of the Paris negotiations.

Island Nations Hold Their Ground

Island Nations, while not quite as unified as they were in 2009, aren't done fighting for the target they believe is a necessity to their survival.

The Marshall Islands Foreign Minister told the World Post in September: "We want to keep everything under 2 degrees--under 1.5 degrees, if possible..."

A roundtable of Pacific Islands passed the Suva Declaration in September as a way to inject 1.5 back into the negotiations. The President of Fiji then took the microphone at the United Nations to plea for limiting "global average temperature increase to less than 1.5 degrees centigrade above pre-industrial levels" - mentioning that Fiji has "plans to move some 45 villages to higher ground, and we have already started."

Last week, an alliance of Caribbean Islands partnered with a renowned poet in Saint Lucia to launch a "1.5 to Stay Alive campaign," calling on Island artists to lend their voice.

And AOSIS has publicly stayed firm. Their latest post from late September states: "AOSIS has long contended that 'well below 1.5 degrees Celsius' is the right global goal to be aiming for, which is evident in the latest science, the UN's own scientific review, and the extent of the extreme weather we are witnessing on every continent."

This past May, Phillipines climate minister, Mary Ann Lucille L. Sering, asked, "How can we possibly subscribe to more than double current warming given what less than 1degC has entailed?"

Just this past weekend, Typhoon Koppu came bearing down on the Philippines--sending over twenty thousand people fleeing from floods and mudslides, and killing at least twelve.

Will 1.5 Find New Life in Paris?

Will Paris see a return of the battle for 1.5 or will all the momentum go towards sealing the deal on 2 degrees? In a sense, the answer is multiple choice.

The latest Paris draft deal--released October 20th--leaves three options, holding global temperature [below 2 degC], [below 2 or 1.5 degC] or [below 1.5 degC], each option literally tucked into brackets for future clarification. (The final choice was literally just added in Bonn--1.5 degC as a standalone target choice was not in the draft earlier this month.)

With most of the negotiating cards from delegates, scientists, and UN leadership already on the table - the main wild cards left to be seen will likely be played by civil society.

The "largest [acts of] climate civil disobedience" are on the calendar for December, and a global movement to "reclaim our power" is already showing its force around the globe. It may be fair to say the Paris summit will be ringed by the most colorful, massive protests and highly orchestrated shows of dissatisfaction of any of its kind in the past 20 years.

If Island Nations can forge their call with those voices coming from the streets, then perhaps 1.5 degC--and the fate of the planet's most vulnerable--may yet stand a fighting chance after all.