As October ended, White House spokesperson Josh Earnest announced that the U.S. would be sending "less than 50" boots-on-the-ground Special Operations forces into northern Syria in an "advise-and-assist" program for Kurdish rebels and their (essentially nonexistent) Arab allies. Only days before, in yet another example of twenty-first-century mission creep, Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter had told Congress that the intensity of U.S. air attacks in Syria would rise "with additional U.S. and coalition aircraft and heavier airstrikes." For this, A-10 and F-15 aircraft were to be deployed to Incirlik Air Base in Turkey.

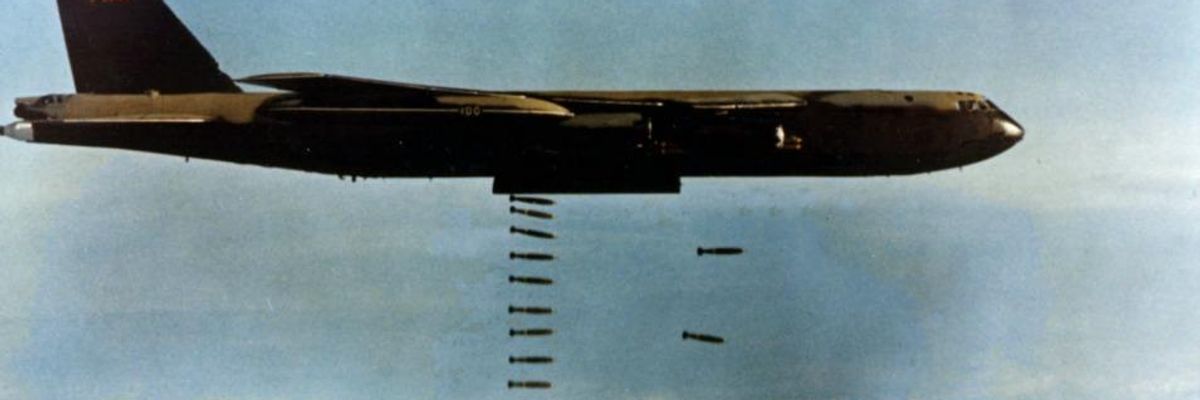

It was the sort of military promise from Washington -- more of the same -- that has grown increasingly familiar in these years and could be summed up by adapting that old DuPont ad line, "better living through chemistry": a better world through bombing. Unfortunately for such plans, the verdict has long been in: air power as a decisive factor in American war in this century has proven a dismal failure. Even in skies that, with the rarest of exceptions, offer no dangers whatsoever (other than mechanical failure) to fighter jets, bombers, and drones, even in situations in which munitions can be delivered to any chosen spot with alacrity and without opposition by aircraft freely patrolling the skies overhead, air power has proven a weapon from hell in every sense of the world. Complete "air superiority" has been a significant factor, as in Libya, in the creation of a string of failed states (and so breeding grounds for terror outfits) across the Greater Middle East. In its post-modern "manhunting" form, grimly named Predator and Reaper drones have managed to kill thousands of leaders, lieutenants, sub-lieutenants, and rank-and-file militants in various terrorist organizations, as well as significant numbers of civilians, including children. Recently leaked documents on Washington's drone assassination campaigns indicate that, in at least one period in Afghanistan, only 10% of those killed were actually targeted for death. And yet the president's drone assassination campaign in several countries (based in part on a White House "kill list" and "terror Tuesday" meetings to decide whom to target) seems only to have helped foster the exponential growth of terror outfits across the Greater Middle East and Africa.

In these years, air power has, in fact, been closely associated with one fiasco or policy disappointment after another. To take a single recent example: President Obama began his "no boots on the ground" air campaign against the Islamic State (IS) and its "caliphate" in Syria and Iraq in September 2014. Now, more than a year and thousands of air strikes later, though large numbers of IS militants and some of its leaders have died, the movement continues to more than hold its own in Iraq, while expanding into new areas of Syria. There is no evidence that Washington's air war in support of well... it's a little unclear who -- now being emulated by the Russians in support of Syria's brutal autocrat Bashar al-Assad -- has met any of its goals.

And yet from all of this, the only conclusion repeatedly drawn in Washington is to do it again. That air power in its various forms has added up to both a war of terror (that is, on civilian populations below) and a war for terror, that it has become a recruitment poster for terror outfits evidently matters not at all. In Washington, no conclusions are seemingly drawn from the actual record of these last 14 years, nor from a far longer historical record of air power disappointments, of repeated times in which much was destroyed and countless people, especially civilians, killed to no decisive effect whatsoever. As Greg Grandin points out in this new piece "Kissinger, the Bombardier," that phenomenon stretches back at least to Vietnam (if not Korea). In his second piece at TomDispatch on the eternal Henry Kissinger (92 and still writing op-eds for the Wall Street Journal), based on his remarkable new book, Kissinger's Shadow: The Long Reach of America's Most Controversial Statesman, Grandin reminds us of what a pioneer in the horrors of modernity the good "doctor" really was.