SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

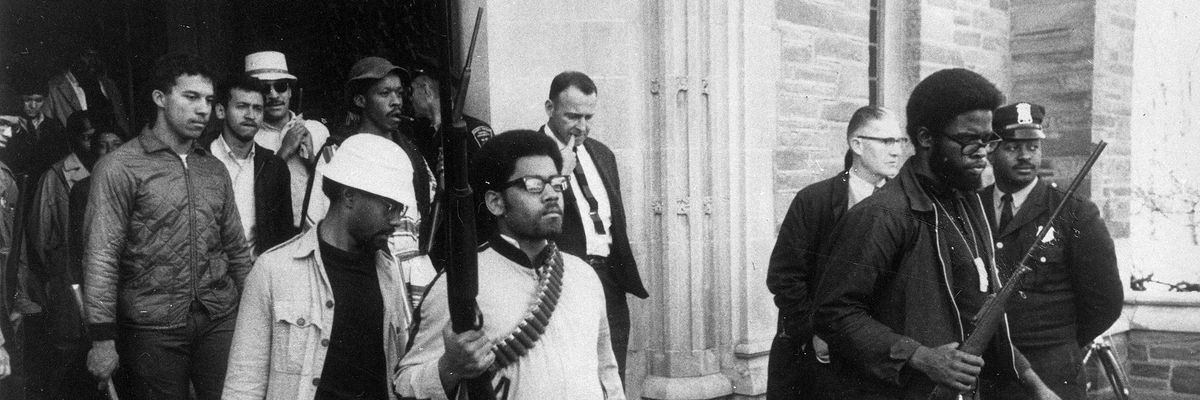

Heavily armed African American students leave Willard Straight Hall during a protest at Cornell University ... 46 years ago. (Photo: Steve Starr/AP)

This week's student protests may be organized on social media, but they're not addressing anything new. The iconic moment of black campus protests was captured way back in 1969, when students from Cornell University's Afro-American Society left Willard Straight Hall carrying rifles and wearing bandoliers, part of a protest against disciplining black students who had advocated for an Africana Studies and Research Center. Forty-six years later, students all over the country continue to protest for their right to exist on a college campus free of racial discrimination.

On Wednesday - just minutes away from Willard Straight Hall - at Ithaca College in upstate New York, more than 1,000 students held a "Solidarity Walk Out" to rally around a vote of no confidence in the college president for allegedly denying the existence of racism within campus security and encouraging surveillance of dissenting faculty and students. It was one in a stream of race-related protests at schools including Claremont McKenna College, Yale University and the University of Missouri.

These actions are more than acts of resistance to systemic racism; these are demands to be respected as students on college campuses. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and visibility of racial justice issues today have perhaps informed the protests, but these student movements have been happening repeatedly since the first person of color stepped on to a campus of higher education.

There is a continuous history of excluding and discriminating against students of color in forms other than outright threats and violence, even before the internet allowed the nationwide broadcast and solidarity of grievances: ethnic studies classes cast as electives instead of mandatory classes or part of legitimate majors; lack of faculty of color; a dearth of funding for student-led diversity initiatives; and the absence of appropriate mental health services for international students and students of color.

A report published by Brown University's newspaper earlier this week found that there was no racial difference in making appointments with campus counseling services but black students there were more than "twice as likely to have reached the seven-session limit and to have received outside help". Brown recently expanded its services to better assist students of color, a change also on the list of demands made by protesting students at the University of Missouri.

These are not hypothetical problems. When protests at the University of Missouri led to the president and chancellor's resignations this week, threats on the app Yik Yak to shoot black students followed. Mizzou students of color said that this was not the first time they have felt unsafe on campus.

And at Ithaca, two alumnae came forward in the fall with their story of how they were allegedly physically attacked by campus security. Many administrators claimed instances of physical violence as isolated anomalies. Protesting students and faculty countered that the acts of violence and denial of racism are both part of a system of institutionalized racism present on primarily white institutions all over the country.

As a recent alumna of Ithaca College, I can attest to a campus environment that boasts a liberal mindset while obstructing students from taking black, Asian or Latino studies courses through the implementation of a strict core curriculum, hiring too few people of color for tenure-track faculty positionsand making no adjustments to the mental health program that would benefit students of color.

Also this week, students at Claremont McKenna College in California gathered in protest of the administration's response to outcry over long-lasting problems with racism on campus. The dean of students had recently responded to a student's article regarding racism on campus by referring to students who "do not fit our CMC mold". The rally was also inspired by a Facebook photograph in which two students dressed up in brownface for Halloween. In response, students demanded a social justice center as well as the resignation of the dean.

And at Yale, more than 1,000 students showed up to a "March of Resilience" after several students reported being denied entry into a fraternity on the basis of their skin color. In addition, after a public announcement to refrain from racist Halloween costumes, students of color became outraged when a faculty member questioned this announcement as an impediment to the freedom of expression.

A nationwide movement among students of color united with the goal to make institutions of higher education inclusive in campus life and curriculum, as well as in admissions, is a necessary part of the current advancement of racial justice in this country. Instead of being used just to satisfy a quota for a liberal agenda, students are fighting to finally be recognized as a legitimate part of academia.

At this moment, it is crucial that students collectively reflect on the histories of their educational institutions and of the organizers who came before them to make sure 46 years from now they are not still struggling to belong in these spaces.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

This week's student protests may be organized on social media, but they're not addressing anything new. The iconic moment of black campus protests was captured way back in 1969, when students from Cornell University's Afro-American Society left Willard Straight Hall carrying rifles and wearing bandoliers, part of a protest against disciplining black students who had advocated for an Africana Studies and Research Center. Forty-six years later, students all over the country continue to protest for their right to exist on a college campus free of racial discrimination.

On Wednesday - just minutes away from Willard Straight Hall - at Ithaca College in upstate New York, more than 1,000 students held a "Solidarity Walk Out" to rally around a vote of no confidence in the college president for allegedly denying the existence of racism within campus security and encouraging surveillance of dissenting faculty and students. It was one in a stream of race-related protests at schools including Claremont McKenna College, Yale University and the University of Missouri.

These actions are more than acts of resistance to systemic racism; these are demands to be respected as students on college campuses. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and visibility of racial justice issues today have perhaps informed the protests, but these student movements have been happening repeatedly since the first person of color stepped on to a campus of higher education.

There is a continuous history of excluding and discriminating against students of color in forms other than outright threats and violence, even before the internet allowed the nationwide broadcast and solidarity of grievances: ethnic studies classes cast as electives instead of mandatory classes or part of legitimate majors; lack of faculty of color; a dearth of funding for student-led diversity initiatives; and the absence of appropriate mental health services for international students and students of color.

A report published by Brown University's newspaper earlier this week found that there was no racial difference in making appointments with campus counseling services but black students there were more than "twice as likely to have reached the seven-session limit and to have received outside help". Brown recently expanded its services to better assist students of color, a change also on the list of demands made by protesting students at the University of Missouri.

These are not hypothetical problems. When protests at the University of Missouri led to the president and chancellor's resignations this week, threats on the app Yik Yak to shoot black students followed. Mizzou students of color said that this was not the first time they have felt unsafe on campus.

And at Ithaca, two alumnae came forward in the fall with their story of how they were allegedly physically attacked by campus security. Many administrators claimed instances of physical violence as isolated anomalies. Protesting students and faculty countered that the acts of violence and denial of racism are both part of a system of institutionalized racism present on primarily white institutions all over the country.

As a recent alumna of Ithaca College, I can attest to a campus environment that boasts a liberal mindset while obstructing students from taking black, Asian or Latino studies courses through the implementation of a strict core curriculum, hiring too few people of color for tenure-track faculty positionsand making no adjustments to the mental health program that would benefit students of color.

Also this week, students at Claremont McKenna College in California gathered in protest of the administration's response to outcry over long-lasting problems with racism on campus. The dean of students had recently responded to a student's article regarding racism on campus by referring to students who "do not fit our CMC mold". The rally was also inspired by a Facebook photograph in which two students dressed up in brownface for Halloween. In response, students demanded a social justice center as well as the resignation of the dean.

And at Yale, more than 1,000 students showed up to a "March of Resilience" after several students reported being denied entry into a fraternity on the basis of their skin color. In addition, after a public announcement to refrain from racist Halloween costumes, students of color became outraged when a faculty member questioned this announcement as an impediment to the freedom of expression.

A nationwide movement among students of color united with the goal to make institutions of higher education inclusive in campus life and curriculum, as well as in admissions, is a necessary part of the current advancement of racial justice in this country. Instead of being used just to satisfy a quota for a liberal agenda, students are fighting to finally be recognized as a legitimate part of academia.

At this moment, it is crucial that students collectively reflect on the histories of their educational institutions and of the organizers who came before them to make sure 46 years from now they are not still struggling to belong in these spaces.

This week's student protests may be organized on social media, but they're not addressing anything new. The iconic moment of black campus protests was captured way back in 1969, when students from Cornell University's Afro-American Society left Willard Straight Hall carrying rifles and wearing bandoliers, part of a protest against disciplining black students who had advocated for an Africana Studies and Research Center. Forty-six years later, students all over the country continue to protest for their right to exist on a college campus free of racial discrimination.

On Wednesday - just minutes away from Willard Straight Hall - at Ithaca College in upstate New York, more than 1,000 students held a "Solidarity Walk Out" to rally around a vote of no confidence in the college president for allegedly denying the existence of racism within campus security and encouraging surveillance of dissenting faculty and students. It was one in a stream of race-related protests at schools including Claremont McKenna College, Yale University and the University of Missouri.

These actions are more than acts of resistance to systemic racism; these are demands to be respected as students on college campuses. The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement and visibility of racial justice issues today have perhaps informed the protests, but these student movements have been happening repeatedly since the first person of color stepped on to a campus of higher education.

There is a continuous history of excluding and discriminating against students of color in forms other than outright threats and violence, even before the internet allowed the nationwide broadcast and solidarity of grievances: ethnic studies classes cast as electives instead of mandatory classes or part of legitimate majors; lack of faculty of color; a dearth of funding for student-led diversity initiatives; and the absence of appropriate mental health services for international students and students of color.

A report published by Brown University's newspaper earlier this week found that there was no racial difference in making appointments with campus counseling services but black students there were more than "twice as likely to have reached the seven-session limit and to have received outside help". Brown recently expanded its services to better assist students of color, a change also on the list of demands made by protesting students at the University of Missouri.

These are not hypothetical problems. When protests at the University of Missouri led to the president and chancellor's resignations this week, threats on the app Yik Yak to shoot black students followed. Mizzou students of color said that this was not the first time they have felt unsafe on campus.

And at Ithaca, two alumnae came forward in the fall with their story of how they were allegedly physically attacked by campus security. Many administrators claimed instances of physical violence as isolated anomalies. Protesting students and faculty countered that the acts of violence and denial of racism are both part of a system of institutionalized racism present on primarily white institutions all over the country.

As a recent alumna of Ithaca College, I can attest to a campus environment that boasts a liberal mindset while obstructing students from taking black, Asian or Latino studies courses through the implementation of a strict core curriculum, hiring too few people of color for tenure-track faculty positionsand making no adjustments to the mental health program that would benefit students of color.

Also this week, students at Claremont McKenna College in California gathered in protest of the administration's response to outcry over long-lasting problems with racism on campus. The dean of students had recently responded to a student's article regarding racism on campus by referring to students who "do not fit our CMC mold". The rally was also inspired by a Facebook photograph in which two students dressed up in brownface for Halloween. In response, students demanded a social justice center as well as the resignation of the dean.

And at Yale, more than 1,000 students showed up to a "March of Resilience" after several students reported being denied entry into a fraternity on the basis of their skin color. In addition, after a public announcement to refrain from racist Halloween costumes, students of color became outraged when a faculty member questioned this announcement as an impediment to the freedom of expression.

A nationwide movement among students of color united with the goal to make institutions of higher education inclusive in campus life and curriculum, as well as in admissions, is a necessary part of the current advancement of racial justice in this country. Instead of being used just to satisfy a quota for a liberal agenda, students are fighting to finally be recognized as a legitimate part of academia.

At this moment, it is crucial that students collectively reflect on the histories of their educational institutions and of the organizers who came before them to make sure 46 years from now they are not still struggling to belong in these spaces.