Venezuela's Food Revolution Has Fought Off Big Agribusiness and Promoted Agroecology

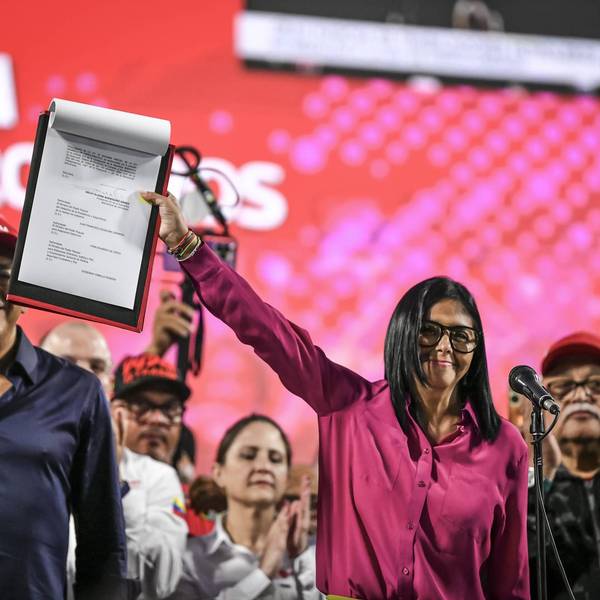

Just days before the progressive National Assembly of Venezuela was dissolved, deputies passed a law which lays the foundation for a truly democratic food system. The country has not only banned genetically modified seeds, but set up democratic structures to ensure that seeds cannot be privatized and indigenous knowledge cannot be sold off to corporations. President Maduro signed the proposal into law before New Year, when a new anti-Maduro Assembly was sworn in.

Since Hugo Chavez's day, Venezuela has always held out against agribusiness, including GM, famously halting 500,000 acres of Monsanto corn in 2004 . In fact, Chavez's formal strategy for the country talked about creating an "an eco-socialist model of production based on a harmonic relationship between humans and nature." The aim, explicitly, was food sovereignty - democratic control of food production.

"Ultimately Venezuela realizes, the only way to make the vision of food sovereignty a reality, is economic democracy."

But that didn't stop agribusiness trying to get a foothold in the country. A war is being waged by big agribusiness, which is trying to monopolize the very means of life - seeds - right across the world. In Africa, Latin America, Asia, even Europe. agribusiness is lobbying for new stronger intellectual property laws so they can more easily take traditional knowledge and resources and patent them, profiting from monopoly rights.

Agribusiness has been lobbying law-makers under the pretence that GM seeds will end food shortages the country is currently experiencing. But Venezuela's strong peasant movement, part of the international peasant network La Via Campesina, fought back. They defeated a 2013 bill that would have provided a 'back door' to GM and initiating a two year democratic process, involving deputies, campaigners, peasants and indigenous groups, to forge a genuinely progressive seed law.

The result is the law passed before Christmas. It promotes agroecological production methods - that's a form of farming that works with nature and avoids chemicals, pesticides and monocultures. It aims to make the county independent of international food markets. It outlaws the privatization of seeds and promotes instead small and medium scale farming and biodiversity. Article 8 "promotes, in a spirit of solidarity, the free exchange of seed and opposes the conversion of seed into intellectual or patented property or any other form of privatization."

Venezuela's step is hugely impressive, first because of the food shortages the country is undergoing - a result of deep dependency on the international market and destabilization efforts coming from inside and outside the country. One commentator points out "Venezuelans are not being fooled by promises of a quick fix to increase food production." Food sovereignty can produce far more than more intensive methods of farming, especially over the long-term.

But second it is impressive because it extends decision-making deep down into Venezuelan society. Ordinary citizens have an ongoing role to play in regulating seeds. In an attempt to decentralize power, a Popular Council has been established, which will join officials and politicians in setting long-term food policy. Ultimately Venezuela realizes, the only way to make the vision of food sovereignty a reality, is economic democracy.

To all those countries fighting off agribusiness, Venezuela has lit a beacon of hope.

An Urgent Message From Our Co-Founder

Dear Common Dreams reader, The U.S. is on a fast track to authoritarianism like nothing I've ever seen. Meanwhile, corporate news outlets are utterly capitulating to Trump, twisting their coverage to avoid drawing his ire while lining up to stuff cash in his pockets. That's why I believe that Common Dreams is doing the best and most consequential reporting that we've ever done. Our small but mighty team is a progressive reporting powerhouse, covering the news every day that the corporate media never will. Our mission has always been simple: To inform. To inspire. And to ignite change for the common good. Now here's the key piece that I want all our readers to understand: None of this would be possible without your financial support. That's not just some fundraising cliche. It's the absolute and literal truth. We don't accept corporate advertising and never will. We don't have a paywall because we don't think people should be blocked from critical news based on their ability to pay. Everything we do is funded by the donations of readers like you. Will you donate now to help power the nonprofit, independent reporting of Common Dreams? Thank you for being a vital member of our community. Together, we can keep independent journalism alive when it’s needed most. - Craig Brown, Co-founder |

Just days before the progressive National Assembly of Venezuela was dissolved, deputies passed a law which lays the foundation for a truly democratic food system. The country has not only banned genetically modified seeds, but set up democratic structures to ensure that seeds cannot be privatized and indigenous knowledge cannot be sold off to corporations. President Maduro signed the proposal into law before New Year, when a new anti-Maduro Assembly was sworn in.

Since Hugo Chavez's day, Venezuela has always held out against agribusiness, including GM, famously halting 500,000 acres of Monsanto corn in 2004 . In fact, Chavez's formal strategy for the country talked about creating an "an eco-socialist model of production based on a harmonic relationship between humans and nature." The aim, explicitly, was food sovereignty - democratic control of food production.

"Ultimately Venezuela realizes, the only way to make the vision of food sovereignty a reality, is economic democracy."

But that didn't stop agribusiness trying to get a foothold in the country. A war is being waged by big agribusiness, which is trying to monopolize the very means of life - seeds - right across the world. In Africa, Latin America, Asia, even Europe. agribusiness is lobbying for new stronger intellectual property laws so they can more easily take traditional knowledge and resources and patent them, profiting from monopoly rights.

Agribusiness has been lobbying law-makers under the pretence that GM seeds will end food shortages the country is currently experiencing. But Venezuela's strong peasant movement, part of the international peasant network La Via Campesina, fought back. They defeated a 2013 bill that would have provided a 'back door' to GM and initiating a two year democratic process, involving deputies, campaigners, peasants and indigenous groups, to forge a genuinely progressive seed law.

The result is the law passed before Christmas. It promotes agroecological production methods - that's a form of farming that works with nature and avoids chemicals, pesticides and monocultures. It aims to make the county independent of international food markets. It outlaws the privatization of seeds and promotes instead small and medium scale farming and biodiversity. Article 8 "promotes, in a spirit of solidarity, the free exchange of seed and opposes the conversion of seed into intellectual or patented property or any other form of privatization."

Venezuela's step is hugely impressive, first because of the food shortages the country is undergoing - a result of deep dependency on the international market and destabilization efforts coming from inside and outside the country. One commentator points out "Venezuelans are not being fooled by promises of a quick fix to increase food production." Food sovereignty can produce far more than more intensive methods of farming, especially over the long-term.

But second it is impressive because it extends decision-making deep down into Venezuelan society. Ordinary citizens have an ongoing role to play in regulating seeds. In an attempt to decentralize power, a Popular Council has been established, which will join officials and politicians in setting long-term food policy. Ultimately Venezuela realizes, the only way to make the vision of food sovereignty a reality, is economic democracy.

To all those countries fighting off agribusiness, Venezuela has lit a beacon of hope.

Just days before the progressive National Assembly of Venezuela was dissolved, deputies passed a law which lays the foundation for a truly democratic food system. The country has not only banned genetically modified seeds, but set up democratic structures to ensure that seeds cannot be privatized and indigenous knowledge cannot be sold off to corporations. President Maduro signed the proposal into law before New Year, when a new anti-Maduro Assembly was sworn in.

Since Hugo Chavez's day, Venezuela has always held out against agribusiness, including GM, famously halting 500,000 acres of Monsanto corn in 2004 . In fact, Chavez's formal strategy for the country talked about creating an "an eco-socialist model of production based on a harmonic relationship between humans and nature." The aim, explicitly, was food sovereignty - democratic control of food production.

"Ultimately Venezuela realizes, the only way to make the vision of food sovereignty a reality, is economic democracy."

But that didn't stop agribusiness trying to get a foothold in the country. A war is being waged by big agribusiness, which is trying to monopolize the very means of life - seeds - right across the world. In Africa, Latin America, Asia, even Europe. agribusiness is lobbying for new stronger intellectual property laws so they can more easily take traditional knowledge and resources and patent them, profiting from monopoly rights.

Agribusiness has been lobbying law-makers under the pretence that GM seeds will end food shortages the country is currently experiencing. But Venezuela's strong peasant movement, part of the international peasant network La Via Campesina, fought back. They defeated a 2013 bill that would have provided a 'back door' to GM and initiating a two year democratic process, involving deputies, campaigners, peasants and indigenous groups, to forge a genuinely progressive seed law.

The result is the law passed before Christmas. It promotes agroecological production methods - that's a form of farming that works with nature and avoids chemicals, pesticides and monocultures. It aims to make the county independent of international food markets. It outlaws the privatization of seeds and promotes instead small and medium scale farming and biodiversity. Article 8 "promotes, in a spirit of solidarity, the free exchange of seed and opposes the conversion of seed into intellectual or patented property or any other form of privatization."

Venezuela's step is hugely impressive, first because of the food shortages the country is undergoing - a result of deep dependency on the international market and destabilization efforts coming from inside and outside the country. One commentator points out "Venezuelans are not being fooled by promises of a quick fix to increase food production." Food sovereignty can produce far more than more intensive methods of farming, especially over the long-term.

But second it is impressive because it extends decision-making deep down into Venezuelan society. Ordinary citizens have an ongoing role to play in regulating seeds. In an attempt to decentralize power, a Popular Council has been established, which will join officials and politicians in setting long-term food policy. Ultimately Venezuela realizes, the only way to make the vision of food sovereignty a reality, is economic democracy.

To all those countries fighting off agribusiness, Venezuela has lit a beacon of hope.