SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

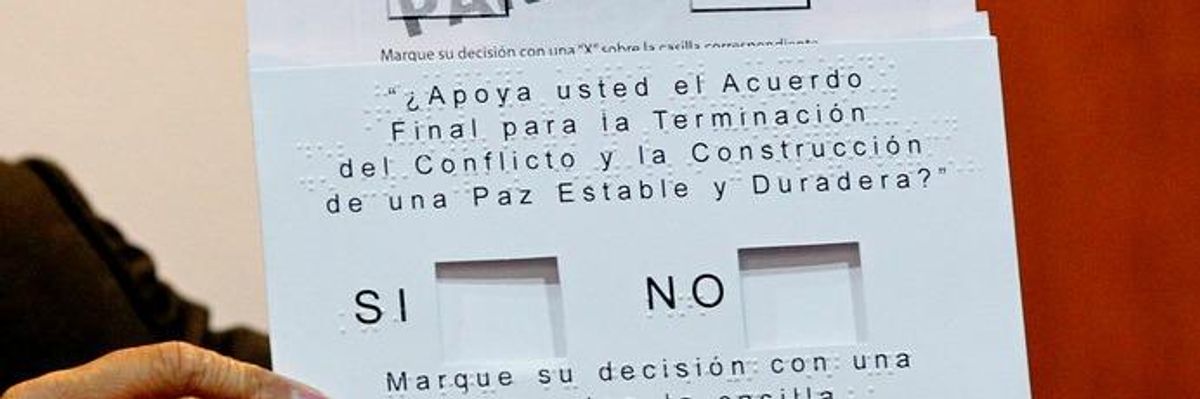

The voting card for the peace accord between the government and the Marxist FARC rebels in Bogota, Colombia. (Photo: Reuters)

On Sept. 26, 2016, the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) are expected to sign a formal agreement to end 50 years of conflict.

More than eight million Colombians have been displaced from their homes or harmed by the violence in the course of the long war. The public, however, still needs to endorse the agreement in a yes-or-no vote to be held on Oct. 2.

If the public votes yes, then the Congress will need to quickly pass legislation for the limited amnesty outlined in the agreement. The Constitutional Court will need to review the legislation to ensure it complies with international human rights law and national law. The FARC will demobilize to special zones with international monitoring, and the government will begin to implement the multifaceted agreement including land, drug policy and electoral reforms.

If the public votes no, then the outcome is uncertain. The Constitutional Court ruled that the public vote is binding only on the executive branch. In other words, if Colombians vote no, the president could not implement or renegotiate the agreement. However, the Congress could try to restart negotiations or pass laws to implement parts of the existing agreement.

Most observers agree, however, that without the legitimacy of the public's support, the agreement reached after four years of negotiations would likely die.

Public opinion polls indicate growing support for the agreement among likely voters, but uncertainty about voter turnout and deep concerns about specific aspects. The public wants peace, but are not united on how to get it. Many disagree with the compromises that would allow guerrillas who committed human rights crimes to avoid serving jail time, and to eventually run for political office.

The basic outlines of the deal include the right of former guerrillas to run for political office, and amnesty for crimes committed during the course of the conflict that are connected to political rebellion. Drug crimes may become eligible for amnesty if they were committed to finance the rebellion, but not for personal profit, or if the proceeds were sent to foreign bank accounts.

Nevertheless, sanctions will be imposed for grave human rights crimes defined in international humanitarian law like sexual crimes, kidnapping, torture, forced displacement and extrajudicial killing. These crimes will be processed under the new "Special Jurisdiction for Peace" tribunal that the peace accords would establish.

Combatants on both sides, FARC and state security forces, who are guilty of grave human rights crimes and decide to confess the truth, pay reparations and acknowledge responsibility would be eligible for a reduced sentence of no more than eight years. The guerrillas would not be in traditional prisons, but would have restricted liberty in designated geographic areas and required to perform community labor to repair damages to victims. Those who do not comply with these conditions would face a special court, and prison sentences up to 20 years.

The FARC would have six seats in Congress with voice, but no vote, until the next elections in 2018. From 2018 to 2026 they would have a guaranteed minimum of five seats in the House and in the Senate for which they will run candidates.

The accords also established a Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence, and Non-Repetition to uncover the causes of abuses and document atrocities.

Critics of the agreement include the popular former president, Alvaro Uribe, and international human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch. They argue that human rights violators would enjoy impunity. They also say Colombia would not be adhering to the international treaty it signed in 2002 - the Rome Statutes obligating punishment for war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Political opponents also fear that the FARC could gain political power and take Colombia down a socialist path. They advocate voting no, and the reopening of negotiations to achieve stiffer punishment.

Proponents include several political parties who are allied with the current president Juan Manuel Santos, his administration and leading Colombian human rights organizations. They argue that the agreement does indeed establish accountability for human rights violators, and point to a supportive public letter from the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. Moreover, there is little guarantee that a new, harsher agreement could be negotiated with a guerrilla force that is not vanquished by military force, but rather is negotiating an end to a conflict.

The innovative nature of this alternative - restorative justice - they argue, is that it focuses on the victims by requiring restitution and labor such as removing land mines from or reconstructing destroyed villages, rather than simply putting perpetrators in prison.

At the same time, it attempts to bring armed combatants back into society. That may help avoid what has happened in the past - in both Colombia and elsewhere - when former combatants were unable to find new job skills or build homes and returned to organized violence.

Participating in politics is a key objective of the FARC - they are laying down arms to pursue their political objectives through peaceful, democratic means. As the government's lead negotiator, Humberto DelaCalle, said, "it is advantageous to Colombia that the FARC, instead of attacking the civilian population, would be present in representative organizations, and would participate in politics without weapons."

The agreement is precedent-setting in several ways.

It will be the first negotiated end to a civil conflict in the world under the new international standards of the 2002 Rome Statutes to hold accountable armed combatants who commit grave human rights abuses.

It will also be the first peace process to have included victims at the negotiating table.

In another innovation, it extends the special justice system to other sectors of the society beyond the FARC, such as civilian sponsors and financiers of paramilitary forces, as well as the government's security forces.

Finally, it will be the first end to a civil war that does not rely primarily on amnesty for all sides, but instead provides new forms of restorative justice. This is a compromise effort to reach peace while also holding perpetrators of human rights abuses accountable, and I believe could serve as a model for the world.

Will the agreement be accepted by a skeptical Colombian public that routinely favors jail time and opposes future political office for FARC members?

The campaign for the referendum has been intense, but research by our Georgia State University team indicates that educating the public about the specifics can increase support, and will be essential to gain popular legitimacy and ensure a sustainable peace.

Our survey of more than 3,000 Colombian citizens showed that those who voted against President Santos and his peace platform in the last election, or those who abstained from voting at all, could be persuaded to support the peace process and specific transitional justice proposals.

Our research also shows that efforts to educate the public could boost the popular legitimacy of the peace process. Specifically, respondents who said they most understood the negotiations were also more likely to support the talks.

Yet, in a Sept. 20 poll, only 7 percent said they know the details of the agreement. Public education on all the elements of the peace deal will thus be crucial to gaining popular legitimacy of the proposal, which is essential if the peace is to become durable and sustainable.

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

On Sept. 26, 2016, the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) are expected to sign a formal agreement to end 50 years of conflict.

More than eight million Colombians have been displaced from their homes or harmed by the violence in the course of the long war. The public, however, still needs to endorse the agreement in a yes-or-no vote to be held on Oct. 2.

If the public votes yes, then the Congress will need to quickly pass legislation for the limited amnesty outlined in the agreement. The Constitutional Court will need to review the legislation to ensure it complies with international human rights law and national law. The FARC will demobilize to special zones with international monitoring, and the government will begin to implement the multifaceted agreement including land, drug policy and electoral reforms.

If the public votes no, then the outcome is uncertain. The Constitutional Court ruled that the public vote is binding only on the executive branch. In other words, if Colombians vote no, the president could not implement or renegotiate the agreement. However, the Congress could try to restart negotiations or pass laws to implement parts of the existing agreement.

Most observers agree, however, that without the legitimacy of the public's support, the agreement reached after four years of negotiations would likely die.

Public opinion polls indicate growing support for the agreement among likely voters, but uncertainty about voter turnout and deep concerns about specific aspects. The public wants peace, but are not united on how to get it. Many disagree with the compromises that would allow guerrillas who committed human rights crimes to avoid serving jail time, and to eventually run for political office.

The basic outlines of the deal include the right of former guerrillas to run for political office, and amnesty for crimes committed during the course of the conflict that are connected to political rebellion. Drug crimes may become eligible for amnesty if they were committed to finance the rebellion, but not for personal profit, or if the proceeds were sent to foreign bank accounts.

Nevertheless, sanctions will be imposed for grave human rights crimes defined in international humanitarian law like sexual crimes, kidnapping, torture, forced displacement and extrajudicial killing. These crimes will be processed under the new "Special Jurisdiction for Peace" tribunal that the peace accords would establish.

Combatants on both sides, FARC and state security forces, who are guilty of grave human rights crimes and decide to confess the truth, pay reparations and acknowledge responsibility would be eligible for a reduced sentence of no more than eight years. The guerrillas would not be in traditional prisons, but would have restricted liberty in designated geographic areas and required to perform community labor to repair damages to victims. Those who do not comply with these conditions would face a special court, and prison sentences up to 20 years.

The FARC would have six seats in Congress with voice, but no vote, until the next elections in 2018. From 2018 to 2026 they would have a guaranteed minimum of five seats in the House and in the Senate for which they will run candidates.

The accords also established a Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence, and Non-Repetition to uncover the causes of abuses and document atrocities.

Critics of the agreement include the popular former president, Alvaro Uribe, and international human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch. They argue that human rights violators would enjoy impunity. They also say Colombia would not be adhering to the international treaty it signed in 2002 - the Rome Statutes obligating punishment for war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Political opponents also fear that the FARC could gain political power and take Colombia down a socialist path. They advocate voting no, and the reopening of negotiations to achieve stiffer punishment.

Proponents include several political parties who are allied with the current president Juan Manuel Santos, his administration and leading Colombian human rights organizations. They argue that the agreement does indeed establish accountability for human rights violators, and point to a supportive public letter from the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. Moreover, there is little guarantee that a new, harsher agreement could be negotiated with a guerrilla force that is not vanquished by military force, but rather is negotiating an end to a conflict.

The innovative nature of this alternative - restorative justice - they argue, is that it focuses on the victims by requiring restitution and labor such as removing land mines from or reconstructing destroyed villages, rather than simply putting perpetrators in prison.

At the same time, it attempts to bring armed combatants back into society. That may help avoid what has happened in the past - in both Colombia and elsewhere - when former combatants were unable to find new job skills or build homes and returned to organized violence.

Participating in politics is a key objective of the FARC - they are laying down arms to pursue their political objectives through peaceful, democratic means. As the government's lead negotiator, Humberto DelaCalle, said, "it is advantageous to Colombia that the FARC, instead of attacking the civilian population, would be present in representative organizations, and would participate in politics without weapons."

The agreement is precedent-setting in several ways.

It will be the first negotiated end to a civil conflict in the world under the new international standards of the 2002 Rome Statutes to hold accountable armed combatants who commit grave human rights abuses.

It will also be the first peace process to have included victims at the negotiating table.

In another innovation, it extends the special justice system to other sectors of the society beyond the FARC, such as civilian sponsors and financiers of paramilitary forces, as well as the government's security forces.

Finally, it will be the first end to a civil war that does not rely primarily on amnesty for all sides, but instead provides new forms of restorative justice. This is a compromise effort to reach peace while also holding perpetrators of human rights abuses accountable, and I believe could serve as a model for the world.

Will the agreement be accepted by a skeptical Colombian public that routinely favors jail time and opposes future political office for FARC members?

The campaign for the referendum has been intense, but research by our Georgia State University team indicates that educating the public about the specifics can increase support, and will be essential to gain popular legitimacy and ensure a sustainable peace.

Our survey of more than 3,000 Colombian citizens showed that those who voted against President Santos and his peace platform in the last election, or those who abstained from voting at all, could be persuaded to support the peace process and specific transitional justice proposals.

Our research also shows that efforts to educate the public could boost the popular legitimacy of the peace process. Specifically, respondents who said they most understood the negotiations were also more likely to support the talks.

Yet, in a Sept. 20 poll, only 7 percent said they know the details of the agreement. Public education on all the elements of the peace deal will thus be crucial to gaining popular legitimacy of the proposal, which is essential if the peace is to become durable and sustainable.

On Sept. 26, 2016, the Colombian government and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) are expected to sign a formal agreement to end 50 years of conflict.

More than eight million Colombians have been displaced from their homes or harmed by the violence in the course of the long war. The public, however, still needs to endorse the agreement in a yes-or-no vote to be held on Oct. 2.

If the public votes yes, then the Congress will need to quickly pass legislation for the limited amnesty outlined in the agreement. The Constitutional Court will need to review the legislation to ensure it complies with international human rights law and national law. The FARC will demobilize to special zones with international monitoring, and the government will begin to implement the multifaceted agreement including land, drug policy and electoral reforms.

If the public votes no, then the outcome is uncertain. The Constitutional Court ruled that the public vote is binding only on the executive branch. In other words, if Colombians vote no, the president could not implement or renegotiate the agreement. However, the Congress could try to restart negotiations or pass laws to implement parts of the existing agreement.

Most observers agree, however, that without the legitimacy of the public's support, the agreement reached after four years of negotiations would likely die.

Public opinion polls indicate growing support for the agreement among likely voters, but uncertainty about voter turnout and deep concerns about specific aspects. The public wants peace, but are not united on how to get it. Many disagree with the compromises that would allow guerrillas who committed human rights crimes to avoid serving jail time, and to eventually run for political office.

The basic outlines of the deal include the right of former guerrillas to run for political office, and amnesty for crimes committed during the course of the conflict that are connected to political rebellion. Drug crimes may become eligible for amnesty if they were committed to finance the rebellion, but not for personal profit, or if the proceeds were sent to foreign bank accounts.

Nevertheless, sanctions will be imposed for grave human rights crimes defined in international humanitarian law like sexual crimes, kidnapping, torture, forced displacement and extrajudicial killing. These crimes will be processed under the new "Special Jurisdiction for Peace" tribunal that the peace accords would establish.

Combatants on both sides, FARC and state security forces, who are guilty of grave human rights crimes and decide to confess the truth, pay reparations and acknowledge responsibility would be eligible for a reduced sentence of no more than eight years. The guerrillas would not be in traditional prisons, but would have restricted liberty in designated geographic areas and required to perform community labor to repair damages to victims. Those who do not comply with these conditions would face a special court, and prison sentences up to 20 years.

The FARC would have six seats in Congress with voice, but no vote, until the next elections in 2018. From 2018 to 2026 they would have a guaranteed minimum of five seats in the House and in the Senate for which they will run candidates.

The accords also established a Commission for the Clarification of Truth, Coexistence, and Non-Repetition to uncover the causes of abuses and document atrocities.

Critics of the agreement include the popular former president, Alvaro Uribe, and international human rights organizations like Human Rights Watch. They argue that human rights violators would enjoy impunity. They also say Colombia would not be adhering to the international treaty it signed in 2002 - the Rome Statutes obligating punishment for war crimes, and crimes against humanity. Political opponents also fear that the FARC could gain political power and take Colombia down a socialist path. They advocate voting no, and the reopening of negotiations to achieve stiffer punishment.

Proponents include several political parties who are allied with the current president Juan Manuel Santos, his administration and leading Colombian human rights organizations. They argue that the agreement does indeed establish accountability for human rights violators, and point to a supportive public letter from the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court. Moreover, there is little guarantee that a new, harsher agreement could be negotiated with a guerrilla force that is not vanquished by military force, but rather is negotiating an end to a conflict.

The innovative nature of this alternative - restorative justice - they argue, is that it focuses on the victims by requiring restitution and labor such as removing land mines from or reconstructing destroyed villages, rather than simply putting perpetrators in prison.

At the same time, it attempts to bring armed combatants back into society. That may help avoid what has happened in the past - in both Colombia and elsewhere - when former combatants were unable to find new job skills or build homes and returned to organized violence.

Participating in politics is a key objective of the FARC - they are laying down arms to pursue their political objectives through peaceful, democratic means. As the government's lead negotiator, Humberto DelaCalle, said, "it is advantageous to Colombia that the FARC, instead of attacking the civilian population, would be present in representative organizations, and would participate in politics without weapons."

The agreement is precedent-setting in several ways.

It will be the first negotiated end to a civil conflict in the world under the new international standards of the 2002 Rome Statutes to hold accountable armed combatants who commit grave human rights abuses.

It will also be the first peace process to have included victims at the negotiating table.

In another innovation, it extends the special justice system to other sectors of the society beyond the FARC, such as civilian sponsors and financiers of paramilitary forces, as well as the government's security forces.

Finally, it will be the first end to a civil war that does not rely primarily on amnesty for all sides, but instead provides new forms of restorative justice. This is a compromise effort to reach peace while also holding perpetrators of human rights abuses accountable, and I believe could serve as a model for the world.

Will the agreement be accepted by a skeptical Colombian public that routinely favors jail time and opposes future political office for FARC members?

The campaign for the referendum has been intense, but research by our Georgia State University team indicates that educating the public about the specifics can increase support, and will be essential to gain popular legitimacy and ensure a sustainable peace.

Our survey of more than 3,000 Colombian citizens showed that those who voted against President Santos and his peace platform in the last election, or those who abstained from voting at all, could be persuaded to support the peace process and specific transitional justice proposals.

Our research also shows that efforts to educate the public could boost the popular legitimacy of the peace process. Specifically, respondents who said they most understood the negotiations were also more likely to support the talks.

Yet, in a Sept. 20 poll, only 7 percent said they know the details of the agreement. Public education on all the elements of the peace deal will thus be crucial to gaining popular legitimacy of the proposal, which is essential if the peace is to become durable and sustainable.