SUBSCRIBE TO OUR FREE NEWSLETTER

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

5

#000000

#FFFFFF

To donate by check, phone, or other method, see our More Ways to Give page.

Daily news & progressive opinion—funded by the people, not the corporations—delivered straight to your inbox.

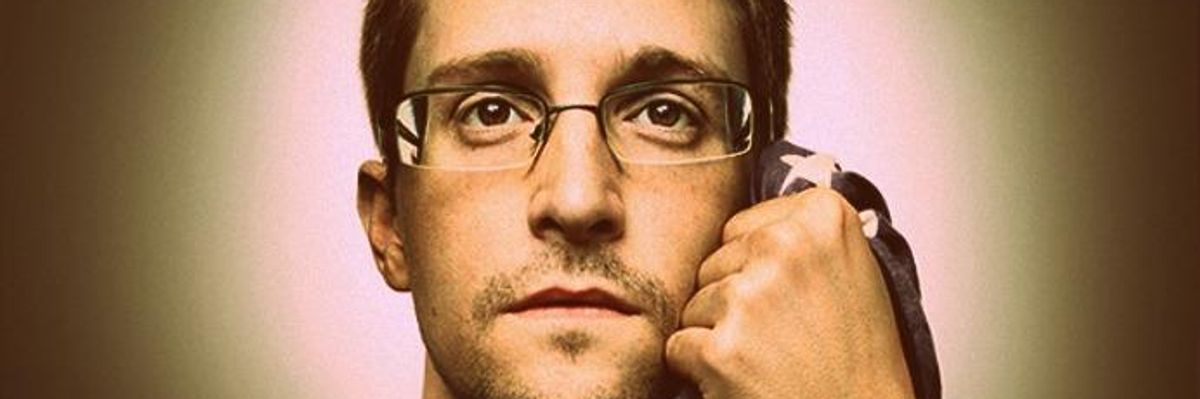

The September 2014 edition of Wired, which featured Snowden embracing the American flag. (Image: Wired magazine cover detail/with overlay)

When Arundhati Roy was preparing, in 2014, for a trip to Moscow to meet Edward Snowden, she was troubled by two things.

One of them was the fact that the meeting was arranged to take place at the Ritz-Carlton, a beacon of luxury, celebrity, and unfettered greed -- a symbol, in short, of what Roy has spent much of her life opposing.

"My last political outing had been some weeks spent walking with Maoist guerrillas and sleeping underneath the stars in the Dandakaranya forest," she wrote. "And this next one was going to be in the Ritz?"

When Arundhati Roy was preparing, in 2014, for a trip to Moscow to meet Edward Snowden, she was troubled by two things.

One of them was the fact that the meeting was arranged to take place at the Ritz-Carlton, a beacon of luxury, celebrity, and unfettered greed -- a symbol, in short, of what Roy has spent much of her life opposing.

"My last political outing had been some weeks spent walking with Maoist guerrillas and sleeping underneath the stars in the Dandakaranya forest," she wrote. "And this next one was going to be in the Ritz?"

The other issue was the cover of the September 2014 edition of Wired, which featured Snowden embracing the American flag. Mainstream media outlets wondered if it was "his first big PR plunder," but Roy, the great opponent of nationalism, looked deeper.

"All I'm saying is: what does that American flag mean to people outside of America?" she asked the actor and screenwriter John Cusack, who has worked with Snowden, and with the legendary whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, at the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

The flag, Roy argues, is not just vapid iconography; it exudes a narrative, a history, one that, while distorted by the powerful, can never be forgotten by the victims.

"The courageous acts of Ellsberg, Snowden, and many others have allowed us to glimpse the inner workings of the system that perpetuates such atrocities, and they have given us information that is necessary in the fight for a better future."

"I am happy -- awed -- that there are people of such intelligence, such compassion, that have defected from the state," she continued. "They are heroic. Absolutely. They've risked their lives, their freedom...but then there's that part of me that thinks...How could you ever have believed in it? What do you feel betrayed by? Is it possible to have a moral state? A moral superpower?"

It is often forgotten that Snowden did once believe in "it," if only for a short time. As he recounts in an interview with the Guardian, "I wanted to fight in the Iraq war because I felt like I had an obligation as a human being to help free people from oppression."

But despite her misgivings -- about the magazine cover, about the opulent hotel, indeed about Snowden himself -- Roy agreed to join John Cusack and Daniel Ellsberg on the trip to Moscow. When they arrived, they confronted a man who knew, or thought he knew, why they wanted to meet him.

"I know why you're here," Snowden said to Roy. "To radicalize me."

Parts of the conversation that followed are transcribed in the newly released book Things That Can and Cannot Be Said, which also includes penetrating discussions between Roy and Cusack on the usual topics -- imperialism, nuclear proliferation, the militarization of police, the corporatization of NGOs.

Ellsberg and Snowden, for reasons that should be obvious, bonded quickly, and had much to talk about. Soon, though, Roy found an opportunity to interject a few queries of her own. She asked about the magazine and the flag, and about why Snowden initially supported the invasion of Iraq "when millions of people all over the world were marching against it."

His forthright reply put Roy at ease.

"I fell for the propaganda," he said.

He fell for the propaganda -- for the nationalistic imagery, for the soaring promises that always accompany deadly military projects -- in the same way then that many of us have fallen for it since. President Obama's promises of greater transparency and a more peaceful future, we must remember, had millions enraptured, inspired, hopeful. Meanwhile, as Snowden told Roy, we were "sleepwalking into a total surveillance state."

"That's the dark future," Snowden said, a situation in which "we have both a super-state that has unlimited capacity to apply force with an unlimited capacity to know [about the people it is targeting] -- and that's a very dangerous combination."

While Snowden's focus is relatively narrow, Roy always returns to the big picture -- to Daniel Berrigan's point that "Every nation-state tends toward the imperial." She also frequently alludes to what Hannah Arendt called humanity's "active, aggressive" capacity to deny the relevant facts, to be deceived by appealing lies, by colorful stories about the past and by fantastical predictions of what the future will bring. Related is the tendency to ignore the historical backdrop, to view events in a vacuum; Donald Trump's rise has done much to bring this tendency to the surface.

Countless pundits, liberal and conservative, have characterized Trump as a unique evil, a radical departure from the civilized political establishment that existed prior to his dangerous candidacy -- a departure, even, from the conservative movement, which has been granted an air of legitimacy by these same commentators.

But, as Roy reminds us, this "civilized political establishment" has never existed. That Trump is an odious character does nothing to change this fact.

"Forget the genocide of American Indians, forget slavery, forget Hiroshima, forget Cambodia, forget Vietnam," Roy said to Cusack, lamenting the historical amnesia -- both willful and not -- of the powerful and the punditry. "I can't understand those people who believe that the excesses are just aberrations."

Excesses, in Roy's view, are embedded in the very concept of empire.

"Isn't the greatness of great nations directly proportionate to their ability to be ruthless, genocidal?" Roy writes. "Doesn't the height of a country's 'success' usually also mark the depths of its moral failure?"

Responding to Trump's infamous promise to "make America great again," many, including the campaign of his opponent, Hillary Clinton, have peddled the line that America is already great -- that while mistakes have been made, America's character and the intentions of its leaders are essentially good.

"The United States is an exceptional nation," Hillary Clinton said on the campaign trail in August. "I believe we are still Lincoln's last, best hope of Earth. We're still Reagan's shining city on a hill. We're still Robert Kennedy's great, unselfish, compassionate country."

Yet on the front page of Wednesday's New York Times, one is forced to confront a rather different story: The story of Suleiman Abdullah Salim, who was imprisoned for years without being convicted of a crime. For months, he was tortured by the CIA.

"Music blasted nearly 24 hours a day while he was chained in solitary confinement so dark that he could not see the shackles on his arms or the walls of his cell," James Risen writes. "The Americans routinely hauled him from his cell to a room where, he said, they hanged him from chains, once for two days. They wrapped a collar around his neck and pulled it to slam him against a wall, he said. And they shaved his head, laid him on a plastic tarp and poured gallons of ice water on him, inducing a feeling of drowning."

Move just beyond the front page, and you'll find the heartbreaking testimony of Mohammed al-Asaadi, a Yemeni man living with his wife and four children at the heart of a nation currently under assault by Saudi Arabia, the heinous dictatorship that receives weaponry and strategic assistance from the United States.

"How will our future be beautiful if they have destroyed Yemen?" Mohammed's 12-year-old daughter Haneen wrote on Facebook.

Internally, American officials have worried about their complicity in the killing of civilians, according to a report by Reuters, but the Obama administration has, nonetheless, continued to approve arms sales to the Saudi Kingdom; in total, the Guardian reports, "The Obama administration has offered to sell $115bn worth of weapons to Saudi Arabia over its eight years in office, more than any previous US administration."

Suleiman Abdullah Salim refers to the prison in which he was tortured as "The Darkness"; "it is," he told the Times, "always there." To look just at America's recent past is to see that The Darkness has been imposed repeatedly on the world's most vulnerable populations: The forceful subversion of democracy to protect corporate interests, bombings in the name of peace, the proliferation of death squads in the name of freedom, torture in the name of security.

These heinous acts are hardly far off in the distant past. The use of Agent Orange against the Vietnamese, for instance, may appear, at a cursory glance, to be the work of a bygone, uncivilized order; progress has been made since those days, it is said. Seems plausible, until you examine recent reports confirming that American forces made extensive use of chemical warfare in Iraq.

And contrary to the narrative favored by our political leaders, these are not merely sharp and temporary diversions from the norm of justice; they are the norm, a norm that is profoundly unjust. The courageous acts of Ellsberg, Snowden, and many others have allowed us to glimpse the inner workings of the system that perpetuates such atrocities, and they have given us information that is necessary in the fight for a better future.

But nothing they revealed should be surprising -- that a superpower such as the United States would relentlessly bomb poor nations (as in the case of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) and seek to establish a surveillance state, under which information is indiscriminately collected and stored, is hardly remarkable.

Nor is it remarkable that those who dare to expose these facts -- and to call them what they are: crimes -- almost inevitably become pariahs, and usually worse. Snowden and Julian Assange are in exile; Jeffrey Sterling and Chelsea Manning are in prison.

_____

After hours of conversation, Roy recalls Ellsberg "lying back on John's bed, Christ-like, with his arms flung open, weeping for what the United States has turned into.

"That the best thing that the best people in our country like Ed can do is to go to prison . . . or be an exile in Russia?" he said. "This is what it's come to in my country . . . it's horrible, you know. . . ."

His despair, Roy notes, is understandable: "He knows now, forty years after he made the Pentagon Papers public, that even though particular individuals have gone, the machine keeps on turning."

The war on whistleblowers continues, unabated. Civilians are maimed and killed by drone strikes, authorized in secret by America's commander in chief, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009. The environment is plundered, both at home and abroad, for profit, while the health of poor communities is disregarded as a mere externality, capitalism's "collateral damage."

All the while, we are told that the very system that got us into this mess of perpetual war and environmental degradation can pull us out -- that the very corporations whose activities have accelerated the warming of the planet can lead the fight for environmental justice, peace, and equality.

"But," Roy argues, echoing George Orwell, "capitalism will fail too." The existential question we face, then, is: what, and who, will replace it?

"We're told, often enough, that as a species we are poised on the edge of the abyss," Roy concludes. "It's possible that our puffed-up, prideful intelligence has outstripped our instinct for survival and the road back to safety has already been washed away. In which case there's nothing much to be done. If there is something to be done, then one thing is for sure: those who created the problem will not be the ones who come up with a solution."

Trump and Musk are on an unconstitutional rampage, aiming for virtually every corner of the federal government. These two right-wing billionaires are targeting nurses, scientists, teachers, daycare providers, judges, veterans, air traffic controllers, and nuclear safety inspectors. No one is safe. The food stamps program, Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are next. It’s an unprecedented disaster and a five-alarm fire, but there will be a reckoning. The people did not vote for this. The American people do not want this dystopian hellscape that hides behind claims of “efficiency.” Still, in reality, it is all a giveaway to corporate interests and the libertarian dreams of far-right oligarchs like Musk. Common Dreams is playing a vital role by reporting day and night on this orgy of corruption and greed, as well as what everyday people can do to organize and fight back. As a people-powered nonprofit news outlet, we cover issues the corporate media never will, but we can only continue with our readers’ support. |

When Arundhati Roy was preparing, in 2014, for a trip to Moscow to meet Edward Snowden, she was troubled by two things.

One of them was the fact that the meeting was arranged to take place at the Ritz-Carlton, a beacon of luxury, celebrity, and unfettered greed -- a symbol, in short, of what Roy has spent much of her life opposing.

"My last political outing had been some weeks spent walking with Maoist guerrillas and sleeping underneath the stars in the Dandakaranya forest," she wrote. "And this next one was going to be in the Ritz?"

The other issue was the cover of the September 2014 edition of Wired, which featured Snowden embracing the American flag. Mainstream media outlets wondered if it was "his first big PR plunder," but Roy, the great opponent of nationalism, looked deeper.

"All I'm saying is: what does that American flag mean to people outside of America?" she asked the actor and screenwriter John Cusack, who has worked with Snowden, and with the legendary whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, at the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

The flag, Roy argues, is not just vapid iconography; it exudes a narrative, a history, one that, while distorted by the powerful, can never be forgotten by the victims.

"The courageous acts of Ellsberg, Snowden, and many others have allowed us to glimpse the inner workings of the system that perpetuates such atrocities, and they have given us information that is necessary in the fight for a better future."

"I am happy -- awed -- that there are people of such intelligence, such compassion, that have defected from the state," she continued. "They are heroic. Absolutely. They've risked their lives, their freedom...but then there's that part of me that thinks...How could you ever have believed in it? What do you feel betrayed by? Is it possible to have a moral state? A moral superpower?"

It is often forgotten that Snowden did once believe in "it," if only for a short time. As he recounts in an interview with the Guardian, "I wanted to fight in the Iraq war because I felt like I had an obligation as a human being to help free people from oppression."

But despite her misgivings -- about the magazine cover, about the opulent hotel, indeed about Snowden himself -- Roy agreed to join John Cusack and Daniel Ellsberg on the trip to Moscow. When they arrived, they confronted a man who knew, or thought he knew, why they wanted to meet him.

"I know why you're here," Snowden said to Roy. "To radicalize me."

Parts of the conversation that followed are transcribed in the newly released book Things That Can and Cannot Be Said, which also includes penetrating discussions between Roy and Cusack on the usual topics -- imperialism, nuclear proliferation, the militarization of police, the corporatization of NGOs.

Ellsberg and Snowden, for reasons that should be obvious, bonded quickly, and had much to talk about. Soon, though, Roy found an opportunity to interject a few queries of her own. She asked about the magazine and the flag, and about why Snowden initially supported the invasion of Iraq "when millions of people all over the world were marching against it."

His forthright reply put Roy at ease.

"I fell for the propaganda," he said.

He fell for the propaganda -- for the nationalistic imagery, for the soaring promises that always accompany deadly military projects -- in the same way then that many of us have fallen for it since. President Obama's promises of greater transparency and a more peaceful future, we must remember, had millions enraptured, inspired, hopeful. Meanwhile, as Snowden told Roy, we were "sleepwalking into a total surveillance state."

"That's the dark future," Snowden said, a situation in which "we have both a super-state that has unlimited capacity to apply force with an unlimited capacity to know [about the people it is targeting] -- and that's a very dangerous combination."

While Snowden's focus is relatively narrow, Roy always returns to the big picture -- to Daniel Berrigan's point that "Every nation-state tends toward the imperial." She also frequently alludes to what Hannah Arendt called humanity's "active, aggressive" capacity to deny the relevant facts, to be deceived by appealing lies, by colorful stories about the past and by fantastical predictions of what the future will bring. Related is the tendency to ignore the historical backdrop, to view events in a vacuum; Donald Trump's rise has done much to bring this tendency to the surface.

Countless pundits, liberal and conservative, have characterized Trump as a unique evil, a radical departure from the civilized political establishment that existed prior to his dangerous candidacy -- a departure, even, from the conservative movement, which has been granted an air of legitimacy by these same commentators.

But, as Roy reminds us, this "civilized political establishment" has never existed. That Trump is an odious character does nothing to change this fact.

"Forget the genocide of American Indians, forget slavery, forget Hiroshima, forget Cambodia, forget Vietnam," Roy said to Cusack, lamenting the historical amnesia -- both willful and not -- of the powerful and the punditry. "I can't understand those people who believe that the excesses are just aberrations."

Excesses, in Roy's view, are embedded in the very concept of empire.

"Isn't the greatness of great nations directly proportionate to their ability to be ruthless, genocidal?" Roy writes. "Doesn't the height of a country's 'success' usually also mark the depths of its moral failure?"

Responding to Trump's infamous promise to "make America great again," many, including the campaign of his opponent, Hillary Clinton, have peddled the line that America is already great -- that while mistakes have been made, America's character and the intentions of its leaders are essentially good.

"The United States is an exceptional nation," Hillary Clinton said on the campaign trail in August. "I believe we are still Lincoln's last, best hope of Earth. We're still Reagan's shining city on a hill. We're still Robert Kennedy's great, unselfish, compassionate country."

Yet on the front page of Wednesday's New York Times, one is forced to confront a rather different story: The story of Suleiman Abdullah Salim, who was imprisoned for years without being convicted of a crime. For months, he was tortured by the CIA.

"Music blasted nearly 24 hours a day while he was chained in solitary confinement so dark that he could not see the shackles on his arms or the walls of his cell," James Risen writes. "The Americans routinely hauled him from his cell to a room where, he said, they hanged him from chains, once for two days. They wrapped a collar around his neck and pulled it to slam him against a wall, he said. And they shaved his head, laid him on a plastic tarp and poured gallons of ice water on him, inducing a feeling of drowning."

Move just beyond the front page, and you'll find the heartbreaking testimony of Mohammed al-Asaadi, a Yemeni man living with his wife and four children at the heart of a nation currently under assault by Saudi Arabia, the heinous dictatorship that receives weaponry and strategic assistance from the United States.

"How will our future be beautiful if they have destroyed Yemen?" Mohammed's 12-year-old daughter Haneen wrote on Facebook.

Internally, American officials have worried about their complicity in the killing of civilians, according to a report by Reuters, but the Obama administration has, nonetheless, continued to approve arms sales to the Saudi Kingdom; in total, the Guardian reports, "The Obama administration has offered to sell $115bn worth of weapons to Saudi Arabia over its eight years in office, more than any previous US administration."

Suleiman Abdullah Salim refers to the prison in which he was tortured as "The Darkness"; "it is," he told the Times, "always there." To look just at America's recent past is to see that The Darkness has been imposed repeatedly on the world's most vulnerable populations: The forceful subversion of democracy to protect corporate interests, bombings in the name of peace, the proliferation of death squads in the name of freedom, torture in the name of security.

These heinous acts are hardly far off in the distant past. The use of Agent Orange against the Vietnamese, for instance, may appear, at a cursory glance, to be the work of a bygone, uncivilized order; progress has been made since those days, it is said. Seems plausible, until you examine recent reports confirming that American forces made extensive use of chemical warfare in Iraq.

And contrary to the narrative favored by our political leaders, these are not merely sharp and temporary diversions from the norm of justice; they are the norm, a norm that is profoundly unjust. The courageous acts of Ellsberg, Snowden, and many others have allowed us to glimpse the inner workings of the system that perpetuates such atrocities, and they have given us information that is necessary in the fight for a better future.

But nothing they revealed should be surprising -- that a superpower such as the United States would relentlessly bomb poor nations (as in the case of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) and seek to establish a surveillance state, under which information is indiscriminately collected and stored, is hardly remarkable.

Nor is it remarkable that those who dare to expose these facts -- and to call them what they are: crimes -- almost inevitably become pariahs, and usually worse. Snowden and Julian Assange are in exile; Jeffrey Sterling and Chelsea Manning are in prison.

_____

After hours of conversation, Roy recalls Ellsberg "lying back on John's bed, Christ-like, with his arms flung open, weeping for what the United States has turned into.

"That the best thing that the best people in our country like Ed can do is to go to prison . . . or be an exile in Russia?" he said. "This is what it's come to in my country . . . it's horrible, you know. . . ."

His despair, Roy notes, is understandable: "He knows now, forty years after he made the Pentagon Papers public, that even though particular individuals have gone, the machine keeps on turning."

The war on whistleblowers continues, unabated. Civilians are maimed and killed by drone strikes, authorized in secret by America's commander in chief, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009. The environment is plundered, both at home and abroad, for profit, while the health of poor communities is disregarded as a mere externality, capitalism's "collateral damage."

All the while, we are told that the very system that got us into this mess of perpetual war and environmental degradation can pull us out -- that the very corporations whose activities have accelerated the warming of the planet can lead the fight for environmental justice, peace, and equality.

"But," Roy argues, echoing George Orwell, "capitalism will fail too." The existential question we face, then, is: what, and who, will replace it?

"We're told, often enough, that as a species we are poised on the edge of the abyss," Roy concludes. "It's possible that our puffed-up, prideful intelligence has outstripped our instinct for survival and the road back to safety has already been washed away. In which case there's nothing much to be done. If there is something to be done, then one thing is for sure: those who created the problem will not be the ones who come up with a solution."

When Arundhati Roy was preparing, in 2014, for a trip to Moscow to meet Edward Snowden, she was troubled by two things.

One of them was the fact that the meeting was arranged to take place at the Ritz-Carlton, a beacon of luxury, celebrity, and unfettered greed -- a symbol, in short, of what Roy has spent much of her life opposing.

"My last political outing had been some weeks spent walking with Maoist guerrillas and sleeping underneath the stars in the Dandakaranya forest," she wrote. "And this next one was going to be in the Ritz?"

The other issue was the cover of the September 2014 edition of Wired, which featured Snowden embracing the American flag. Mainstream media outlets wondered if it was "his first big PR plunder," but Roy, the great opponent of nationalism, looked deeper.

"All I'm saying is: what does that American flag mean to people outside of America?" she asked the actor and screenwriter John Cusack, who has worked with Snowden, and with the legendary whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, at the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

The flag, Roy argues, is not just vapid iconography; it exudes a narrative, a history, one that, while distorted by the powerful, can never be forgotten by the victims.

"The courageous acts of Ellsberg, Snowden, and many others have allowed us to glimpse the inner workings of the system that perpetuates such atrocities, and they have given us information that is necessary in the fight for a better future."

"I am happy -- awed -- that there are people of such intelligence, such compassion, that have defected from the state," she continued. "They are heroic. Absolutely. They've risked their lives, their freedom...but then there's that part of me that thinks...How could you ever have believed in it? What do you feel betrayed by? Is it possible to have a moral state? A moral superpower?"

It is often forgotten that Snowden did once believe in "it," if only for a short time. As he recounts in an interview with the Guardian, "I wanted to fight in the Iraq war because I felt like I had an obligation as a human being to help free people from oppression."

But despite her misgivings -- about the magazine cover, about the opulent hotel, indeed about Snowden himself -- Roy agreed to join John Cusack and Daniel Ellsberg on the trip to Moscow. When they arrived, they confronted a man who knew, or thought he knew, why they wanted to meet him.

"I know why you're here," Snowden said to Roy. "To radicalize me."

Parts of the conversation that followed are transcribed in the newly released book Things That Can and Cannot Be Said, which also includes penetrating discussions between Roy and Cusack on the usual topics -- imperialism, nuclear proliferation, the militarization of police, the corporatization of NGOs.

Ellsberg and Snowden, for reasons that should be obvious, bonded quickly, and had much to talk about. Soon, though, Roy found an opportunity to interject a few queries of her own. She asked about the magazine and the flag, and about why Snowden initially supported the invasion of Iraq "when millions of people all over the world were marching against it."

His forthright reply put Roy at ease.

"I fell for the propaganda," he said.

He fell for the propaganda -- for the nationalistic imagery, for the soaring promises that always accompany deadly military projects -- in the same way then that many of us have fallen for it since. President Obama's promises of greater transparency and a more peaceful future, we must remember, had millions enraptured, inspired, hopeful. Meanwhile, as Snowden told Roy, we were "sleepwalking into a total surveillance state."

"That's the dark future," Snowden said, a situation in which "we have both a super-state that has unlimited capacity to apply force with an unlimited capacity to know [about the people it is targeting] -- and that's a very dangerous combination."

While Snowden's focus is relatively narrow, Roy always returns to the big picture -- to Daniel Berrigan's point that "Every nation-state tends toward the imperial." She also frequently alludes to what Hannah Arendt called humanity's "active, aggressive" capacity to deny the relevant facts, to be deceived by appealing lies, by colorful stories about the past and by fantastical predictions of what the future will bring. Related is the tendency to ignore the historical backdrop, to view events in a vacuum; Donald Trump's rise has done much to bring this tendency to the surface.

Countless pundits, liberal and conservative, have characterized Trump as a unique evil, a radical departure from the civilized political establishment that existed prior to his dangerous candidacy -- a departure, even, from the conservative movement, which has been granted an air of legitimacy by these same commentators.

But, as Roy reminds us, this "civilized political establishment" has never existed. That Trump is an odious character does nothing to change this fact.

"Forget the genocide of American Indians, forget slavery, forget Hiroshima, forget Cambodia, forget Vietnam," Roy said to Cusack, lamenting the historical amnesia -- both willful and not -- of the powerful and the punditry. "I can't understand those people who believe that the excesses are just aberrations."

Excesses, in Roy's view, are embedded in the very concept of empire.

"Isn't the greatness of great nations directly proportionate to their ability to be ruthless, genocidal?" Roy writes. "Doesn't the height of a country's 'success' usually also mark the depths of its moral failure?"

Responding to Trump's infamous promise to "make America great again," many, including the campaign of his opponent, Hillary Clinton, have peddled the line that America is already great -- that while mistakes have been made, America's character and the intentions of its leaders are essentially good.

"The United States is an exceptional nation," Hillary Clinton said on the campaign trail in August. "I believe we are still Lincoln's last, best hope of Earth. We're still Reagan's shining city on a hill. We're still Robert Kennedy's great, unselfish, compassionate country."

Yet on the front page of Wednesday's New York Times, one is forced to confront a rather different story: The story of Suleiman Abdullah Salim, who was imprisoned for years without being convicted of a crime. For months, he was tortured by the CIA.

"Music blasted nearly 24 hours a day while he was chained in solitary confinement so dark that he could not see the shackles on his arms or the walls of his cell," James Risen writes. "The Americans routinely hauled him from his cell to a room where, he said, they hanged him from chains, once for two days. They wrapped a collar around his neck and pulled it to slam him against a wall, he said. And they shaved his head, laid him on a plastic tarp and poured gallons of ice water on him, inducing a feeling of drowning."

Move just beyond the front page, and you'll find the heartbreaking testimony of Mohammed al-Asaadi, a Yemeni man living with his wife and four children at the heart of a nation currently under assault by Saudi Arabia, the heinous dictatorship that receives weaponry and strategic assistance from the United States.

"How will our future be beautiful if they have destroyed Yemen?" Mohammed's 12-year-old daughter Haneen wrote on Facebook.

Internally, American officials have worried about their complicity in the killing of civilians, according to a report by Reuters, but the Obama administration has, nonetheless, continued to approve arms sales to the Saudi Kingdom; in total, the Guardian reports, "The Obama administration has offered to sell $115bn worth of weapons to Saudi Arabia over its eight years in office, more than any previous US administration."

Suleiman Abdullah Salim refers to the prison in which he was tortured as "The Darkness"; "it is," he told the Times, "always there." To look just at America's recent past is to see that The Darkness has been imposed repeatedly on the world's most vulnerable populations: The forceful subversion of democracy to protect corporate interests, bombings in the name of peace, the proliferation of death squads in the name of freedom, torture in the name of security.

These heinous acts are hardly far off in the distant past. The use of Agent Orange against the Vietnamese, for instance, may appear, at a cursory glance, to be the work of a bygone, uncivilized order; progress has been made since those days, it is said. Seems plausible, until you examine recent reports confirming that American forces made extensive use of chemical warfare in Iraq.

And contrary to the narrative favored by our political leaders, these are not merely sharp and temporary diversions from the norm of justice; they are the norm, a norm that is profoundly unjust. The courageous acts of Ellsberg, Snowden, and many others have allowed us to glimpse the inner workings of the system that perpetuates such atrocities, and they have given us information that is necessary in the fight for a better future.

But nothing they revealed should be surprising -- that a superpower such as the United States would relentlessly bomb poor nations (as in the case of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) and seek to establish a surveillance state, under which information is indiscriminately collected and stored, is hardly remarkable.

Nor is it remarkable that those who dare to expose these facts -- and to call them what they are: crimes -- almost inevitably become pariahs, and usually worse. Snowden and Julian Assange are in exile; Jeffrey Sterling and Chelsea Manning are in prison.

_____

After hours of conversation, Roy recalls Ellsberg "lying back on John's bed, Christ-like, with his arms flung open, weeping for what the United States has turned into.

"That the best thing that the best people in our country like Ed can do is to go to prison . . . or be an exile in Russia?" he said. "This is what it's come to in my country . . . it's horrible, you know. . . ."

His despair, Roy notes, is understandable: "He knows now, forty years after he made the Pentagon Papers public, that even though particular individuals have gone, the machine keeps on turning."

The war on whistleblowers continues, unabated. Civilians are maimed and killed by drone strikes, authorized in secret by America's commander in chief, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2009. The environment is plundered, both at home and abroad, for profit, while the health of poor communities is disregarded as a mere externality, capitalism's "collateral damage."

All the while, we are told that the very system that got us into this mess of perpetual war and environmental degradation can pull us out -- that the very corporations whose activities have accelerated the warming of the planet can lead the fight for environmental justice, peace, and equality.

"But," Roy argues, echoing George Orwell, "capitalism will fail too." The existential question we face, then, is: what, and who, will replace it?

"We're told, often enough, that as a species we are poised on the edge of the abyss," Roy concludes. "It's possible that our puffed-up, prideful intelligence has outstripped our instinct for survival and the road back to safety has already been washed away. In which case there's nothing much to be done. If there is something to be done, then one thing is for sure: those who created the problem will not be the ones who come up with a solution."